I actually visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by my favorite artist, Hiroshige Ando, to see how the scenes look like today.

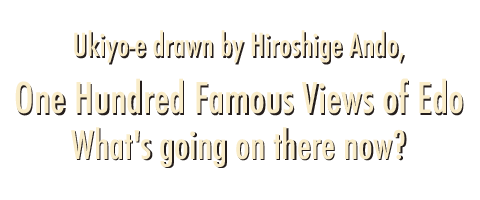

051, "Sannomatsuri Festival Procession at Kojimachi 1-chome," depicts the festival of Hiyoshi Sanno Gongen Shrine, or Sanno Matsuri, from present-day Uchibori Street.

First, as always, please check the map to see where this painting was done. I added a red gradation to the area where I think Hiroshige's point of view would have been. The view is from the area in front of the National Theatre, which is now Uchibori Street, looking north toward Hanzomon.

The topography of this area has not changed much since then. So I put a map of that time on top. Hanzomon is the starting point of the Koshu Kaido highway, which runs almost westward, passing through Yotsuya-gomon, Naito-Shinjuku, and Fuchu.

The area from Hanzomon to Koshu Kaido was called "Koji-machi," the rice-biased name that gives the title to this painting. Since this road leads to Fuchu, where the national government of Musashi Province was located during the Ritsuryo period, it is said to have been called "Kokufu-michi," which is read as "Koji," and thus Koji-machi.

This is the same as the JR Tokaido Line's "Kokufutsu," which is read as "Kouzu. The word "Tsu" means "port.

Now, let's look at Hiroshige's painting in detail.

First, in the upper part of the picture, on the far left, is the white tail of the Odenmacho float, a bird called the Kanko bird. Below it is a drum called Kanko, and further down is a blue Chinese-style streamer. In fact, the streamers seem to have been quite colorful. In Hiroshige's painting, they are tied up so that they do not flutter.

It is said to be a metaphor for a good world where the moss grows on the Kanko drum and the birds perch on it when the monarch's government is functioning well.

This Kanko drum is a drum that is played by those who want to give an opinion to the imperial court because of ancient Chinese history. If the monarch's politics is working well, moss grows on this drum and birds stop. It seems to be an analogy that it is a good world.

In the distance, beyond the moat, there is another float that is about to pass through Hanzomon. This is the Minamidenma-cho float carrying a monkey carrying a certain gohei, a sacred offering from the mountain of Sanno, and the monkey is dressed in a gold cap and hunting robe. The monkey is dressed in a golden raven hat and hunting robe, and the humble streamers are tied up.

At the bottom of the painting, a procession of people wearing hanagasa (flower hats) along with floats are heading together along the side of the moat in the direction of Hanzomon.

Here is a drawing of the Sanno Gongen ritual by Utagawa Kuniteru, drawn around the Tempou period.

The origin of the Sanno Gongen Shrine is ancient. When Ota Dokan built his castle in Edo, he requested the Sanno Shrine in Kawagoe as a god of protection, and later, Tokugawa Ieyasu made the Sanno Gongen Shrine the shrine to protect the castle.

The Sanno Matsuri and the Kanda Matsuri are the two festivals where more than 50 such floats are lined up. This festival was called "Tenka Matsuri" by the common people of Edo (Tokyo) because it was held in front of the Fukiage Gomon (Gate), where the floats entered Edo Castle from Hanzomon Gate and were presented to the Shogunate. The festival was so costly that it was held in alternating years starting in 1681. Since Hiroshige's painting was published in July 1856, it depicts the Sanno Festival held in the previous month.

However, in Hiroshige's painting, there is an unnaturalness that is not typical of the Sanno Festival. Originally, the order of the floats was the flamboyant Kanko bird first, and the monkey floats second. This order is the same for both the Sanno Festival and the Kanda Festival. In Hiroshige's painting, the Kanko bird, which is supposed to be a flamboyant five-colored bird, has a white tail, even though it is the Sanno Festival. In his painting, the Kanko bird, which is supposed to be a flamboyant five-colored bird, has a white tail.

Please take a look at the picture of the Kanda Myojin ritual at the Edo-Tokyo Museum. You can see that the Kanko bird is white except for its torsos. You can clearly see that the head of the Kanda Festival is a white Kanko bird, while the Sanno Festival is a flamboyant Kanko bird of five colors. You can also see a model that well reproduces what it was like at that time.

During the great earthquake of the Ansei period, the year before the Sanno Festival, the roof of Hanzomon Gate, the turrets, and the surrounding stone walls collapsed, causing extensive damage throughout Edo Castle. As a result, the Ujiko (shrine parishioners) asked to refrain from holding the festival itself, but the Shogunate issued a notice to hold the festival as usual. The repair of Hanzomon was not actually completed until May of the following year, so at the time of the Sanno Festival that year, Hanzomon was still under construction.

On June 15, the actual day of the Sanno Festival, it is recorded that it rained and thundered in Edo from the afternoon, and the festival itself did not seem to be that exciting.

In the book "Mystery Solving Hiroshige: Edo 100" written by Minoru Harashida, he explains the unnaturalness of these events as follows

If the festival is depicted in detail as a fact, the Hanzomon gate under repair will also be blatantly depicted, and even military secrets will be depicted. Hiroshige may have deliberately depicted the festival in a way that was not true, in order to make an excuse when he was censured by the shogunate.

I actually went to this place. It doesn't look much different from the view at that time.

This is the present-day Hanzomon Gate. Behind this is the Fukiage Palace, where the Shogunate was held. Until the early Showa period , this area was also open to the public as a public road.

This is across from the Uchibori Street viewpoint. On the left is the Supreme Court and on the right is the National Theatre.

This is a photograph of the Sakurada Gate area behind the viewpoint. The red tower in front is the Metropolitan Police Department, the right is the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, and the front is the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. Hibiya Midtown stands high behind the Metropolitan Police Department.

I swung the camera from the viewpoint, through the Imperial Palace, to Hibiya.

I inserted a current photo into Hiroshige's painting. Although Hanzomon is not visible due to the shadows of the trees, the actual scenery in this area is thought to be as it was then.

It makes sense that Hiroshige was afraid of being censured by the shogunate, so he had to put a lot of thought into his paintings. In those days, the shogunate imposed various restrictions on publications. Publications that did not meet the will of the shogunate were banned or recalled without mercy, and profits were confiscated, not only to the publishers but also to the artists, printers, and engravers. It is said that a large number of works depicting the Great Ansei Earthquake were banned.

According to the records, the earthquake reportage "Ansei mimono zhi" was banned and the publisher was punished by execution.

In order to avoid such a situation, Hiroshige painted a small picture of Hanzomon under repair, made the flamboyant festival look docile, and even changed the order of the floats to use them as a rhetorical escape route in case the Shogunate came to blame him. There is a part of me that would like to see the current mass media, which is always on the lookout for discoveries and flattered by the system, learn from this.

I went to visit One Hundred Famous Views of Edo painted by my favorite artist, Hiroshige Ando, to see how the scenes look now.

I went to visit One Hundred Famous Views of Edo painted by my favorite artist, Hiroshige Ando, to see how the scenes look now.

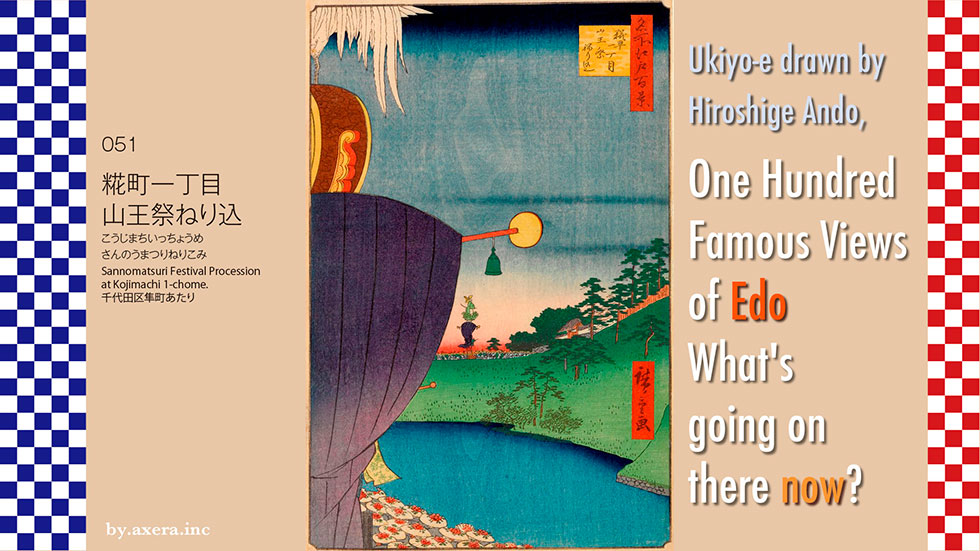

"Akasaka Paulownia Field" in 052 is a view from the south side of the 2-chome police box on today's Akasaka Tamachi Street, looking toward the current Prime Minister's office over the then existing Tameike pond.

First of all, take a look at the current Applemap to see where this picture is viewed from. I added a red gradation to the point where Hiroshige's viewpoint would have been.

I overlaid an old map of the Genroku era (1688-1704), taking into account the scale and direction. You can see that the area between Akasaka-mitsuke station and Tameike-sanno station on today's Sotobori Street was a large pond. This pond was formed when spring water from Kojimachi, Samegabashi, and Shimizu Valley accumulated in a depression, and is said to have existed since the time when Ieyasu Tokugawa entered Edo.

In 1606, Yukinaga Asano, the feudal lord of Wakayama, who felt indebted to Ieyasu Tokugawa, built a weir around Toranomon and expanded the pond to make it serve as the outer moat of Edo Castle. This pond came to be called Tameike, and it supplied drinking water to the city to the south until about 50 years later, when Tamagawa Josui was completed and supplied water to Toranomon via a canal.

I covered this map with a map from the previous year, when Hiroshige's painting was done. You can see the word "paulownia field" in the place where Hiroshige's viewpoint is. This area was called Kiribatake (paulownia field) because paulownia trees were planted to strengthen the banks of the pond during the Kyoto era (1716-35). However, after the Tempo Reforms, the paulownia trees were gradually cut down and the area did not look like a field.

Before painting this picture, Hiroshige painted this paulownia field in his picture book Edo Souvenirs. In his commentary, he regrets that people do not appreciate such a good view because they are used to seeing it.

In addition, Edo Meisho also published this painting in a horizontal position two years before it was published. It depicts a paulownia field with a teahouse in the foreground and a teahouse on the other side of the river with Sanno Gongen in the background.

Now let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

This painting is said to be from June, early summer, because of the paulownia blossoms, and the dark clouds in the upper part of the painting. In the middle of the painting, there is a paulownia tree, and in the distance, the foot of the Sanno shrine and a building that looks like a teahouse.

Take a look at the drawing of the year depicted here. In the direction of the painting, there are supposed to be Enjo-in and Jouju-in, which are the sub-institutions of the Sanno-sha, and the Naito Kii governor's subordinate residence, but in fact there were teahouses and brothels lining the shore of the pond.

Tameike Pond was a famous place for funa and carp because Hidetada Tokugawa, the second shogun of Japan, imported funa from Lake Biwa and carp from the Yodo River and released them there. Many lotuses were also planted in the pond, making it a famous lotus spot along with Ueno Shinobazu-no-ike. The black dot in the painting is a lotus.

As a scenic place of paulownia wood and lotuses, it seems to have been crowded until around 1877.

I inserted the shape of the pond into the current Applemap street view of the area. You can see that it was quite a large pond.

I actually went to this place. It's a picture of a building, but it's the view from the current location on Tamachi Street. This is where the pond should have been.

I turned the camera from the left to the right of the viewpoint on Tamachi Street, which must have been a forest of paulownia trees at the time.

I walked out to Sotobori-dori Street, where I had a clear view, and took this picture looking in the direction of the viewpoint. The Prime Minister's official residence can be seen behind the Sanno Park Tower on the left.

This is the entrance to the Sanno Hie Shrine, on what is now Sotobori Street. The unique shape of the torii gate is eye-catching.

I actually tried to fit Hiroshige's painting with a picture of the present from my point of view. However, this only shows the building in front of me.

So, I went out to Sotobori Street and fitted in the view I saw, and while I was at it, I brought down the clouds that were about to start falling. Here, in those days, you would be standing completely in the middle of a pond.

As a result of the maintenance work that began in 1877, the entrance to Toranomon was lowered, and the reservoir became as narrow as a stream. The dried-up land became farmland, and later, with the construction of roads, it became the Sotobori Street we know today. The remaining paulownia trees, which had become large, were cut down because they were in the way of the farmland and road development, and the scenic reservoir began to change its appearance drastically.

The area where the paulownia trees are planted in Hiroshige's painting is now the Tamachi-dori building district, with the Sanno Park Tower in the center of the pond, and the entrance to the Prime Minister's residence by the pond at the back of the painting, where police officers stand guard every day.

It was only about 150 years ago, but there is no sign of it now.

I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by my favorite artist, Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like today.

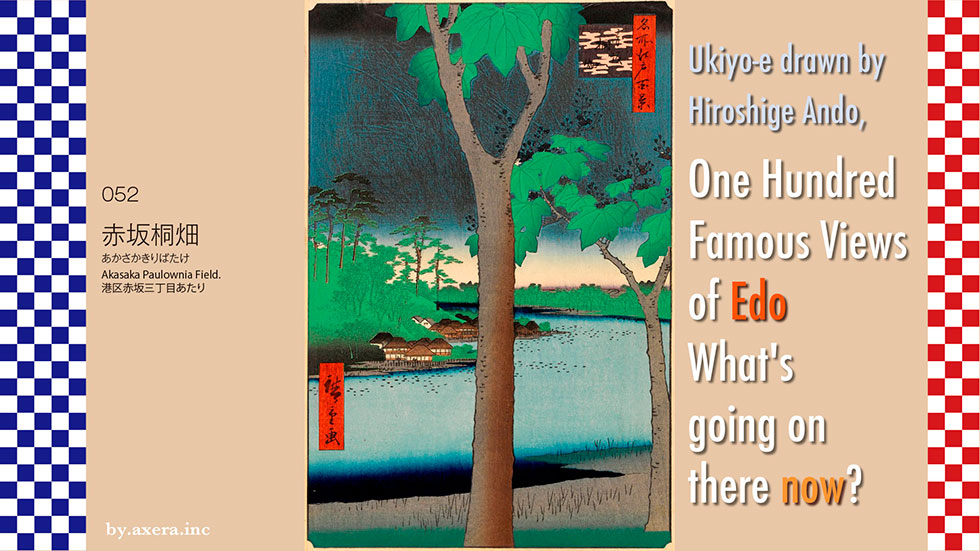

053 "Zojoji Temple Pagoda and Akabane" is a view looking toward Akabanebashi Bridge through the five-story pagoda that was located in the precincts of Zojoji Temple at that time.

First of all, I explored Hiroshige's point of view from a map. It is said that there was a five-story pagoda on top of the Shibamaruyama burial mound, which is now located in Shiba Park. The pagoda was built by Sakai Utanokami, the first Grand Elder of the Edo Shogunate and Lord of Himeji Castle, and was once destroyed by fire in 1806, but was later rebuilt by the Sakai family. It can be seen clearly from boats floating in Edo Bay, and was a landmark like the Tokyo Tower is today.

I added a red gradation to Hiroshige's viewpoint. I superimposed an old map of Tenpo on it.

This place marked "Arima Gemba" was the upper residence of Arima Nakatsutomu Taifu of the Chikugo Kurume Clan, who was in charge of the security of Zojoji Temple. Today, the area is home to Saiseikai Hospital, International University of Health and Welfare, Minato Health Center, and Mita International Building.

This sub-institute of Zojoji Temple, marked "Meuseiin", still exists as Myojoin.

This triangular area is the current location of Tokyo Tower, and Zojoji Temple donated the land that had been used as a cemetery when the tower was built.

I put the current map back.

In the Edo Meisho Zue (Illustrated Guide to Famous Places in Edo), Gessin Saito depicted the vast Zojoji Temple in a series of five pages. The five-story pagoda is depicted on the leftmost page.

Zojoji Temple was built around the 9th century by a disciple of Kukai as Komyoji Temple in the Kojimachi area. In terms of feng shui, Kan'eiji Temple of the Tendai sect was located in Ueno, the demon's gate to Edo, and Zojoji Temple was moved to its current location to suppress the turf at the back demon's gate.

This is a full view of Zojoji drawn by Hiroshige, although the five-story pagoda is missing.

Zojoji Temple, the Kanto head temple of the Jodo sect of Buddhism, was particularly famous for its bell tower and five-story pagoda that could be heard as far as Boso, but the mausoleum of the Tokugawa family and the five-story pagoda were destroyed in air raids during World War II.

Please see the map that shows the size of Zojoji Temple at that time. The red area was the site of Zojoji Temple and its sub-institutes. It is said that the Jodo sect of Buddhism, Zojoji Temple, had a power comparable to that of Chion-in Temple in Kyoto, the head temple of the Tokugawa family, because it was under the generous patronage of the Tokugawa family. The river to the south was the lower reaches of the Shibuya River, which became the Furukawa River, passed through Azabu Juban, became the Akabane River here, and flowed into the sea through Kanasugi Bridge. It is now covered by the Metropolitan Expressway Loop Line.

Now let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

On the right is a large five-story pagoda, and on the left is a fire watchtower. This is the tallest fire watchtower in Edo, built by the Arima family, who were in charge of guarding Zojoji Temple, and was a famous landmark in its own right.

The white banner coming out of the hazy clouds in the middle is that of the Suitengu Shrine, whose deity is the water god of the Chikugo River. The shrine is located on the west side of the house, and it was crowded with visitors on the fifth day of every month, when the public was allowed to pay homage to the goddess of water, as it was said to be beneficial for safe childbirth, protection from water disasters, and restaurant business. The Suitengu shrine was later moved to Aoyama in 1871 when the Arima residence was relocated, and then to Ningyocho the following year.

The bridge in the lower center of the picture is Akabanebashi. Beyond that, under the black forest in the picture, surrounded by a long fence, is the Arima family's upper residence, and below that, in front of the bridge, there is a guardhouse.

Hiroshige painted Akabane-bashi Bridge from a lower angle in his Toto Meisho. The upper residence of the Arima family, the banner of the Suitengu shrine, the fire watchtower on the left, and the people coming and going on the Akabanebashi bridge are all depicted peacefully. It conveys a peaceful era.

Hiroshige II painted a wide view of Akabanebashi Bridge in Tohto Meisho, depicted over the Nakanohashi Bridge upstream. The painting is seen from the complete opposite perspective of Hiroshige I's. The splendid Kamiyashiki (upper residence) on the right, the banner of Suitengu Shrine, and the fire watchtower are also depicted, while the red five-story pagoda is depicted in a small distance on the left. Many people of various occupations are depicted, giving us a glimpse into the lives of the common people of Edo at that time.

Hiroshige II also depicted the same angle in a vertical painting in Akabane of Edo Meisho Zue. This is the painting on the left. The composition is perfected as a painting, and the commentary describes the bustle of the area.

The painting on the right, a collaboration between Hiroshige I and Toyokuni, depicts a mother and child who have come to see the fire watchtower about to cross the Akabane Bridge. On the other side of the bridge, the fire watchtower and the upper residence of the Arima family are depicted in detail. As you can see, the upper residence of the Arima family was surrounded by a sea cucumber wall, and the front gate was painted red.

I found a book with photos of what it was like back then. It is called "Edo Tokyo in Pictures" by Shinchosha. It was taken by Felix Beato, who visited Japan at the end of the Edo period. It's in black and white, so you can't see the colors, but it starts from the upper residence of the Arima family on the left side and expands to the right. On the way, a surprisingly large Furukawa river appears, and on the right side of the river, you can see the present-day Higashi-Azabu district.

I actually went to this place. The area around the Shiba-Maruyama Tumulus is now Shiba Park, and there is no trace of the five-story pagoda. The view toward Akabanebashi Bridge is almost impossible to see due to the trees standing in the way.

Even if you go to the south side of the mountain, you can only see a little bit.

I went down to the road. The apartment in the middle is a tower apartment building at the foot of Akabanebashi Bridge. The building on the left is Myojo-in Temple, which I saw on an old map.

Please also see the video from this angle.

As you swing the camera to the right, you can see Tokyo Tower and the Grand Prince Hotel. At that time, this was also the site of Zojoji Temple. If you compare it to Beato's photo, you can see the amazing transformation it has undergone.

Take a look at the current Applemap street view. At the end of the tennis court is Myojo-in Temple, and beyond that is Akabanebashi Bridge, and you can see the Metropolitan Expressway Loop Line running above along the old river. The five-storied pagoda of Asakusa was inserted into the picture to show the atmosphere. When Hiroshige painted it, the five-story pagoda was red.

Finally, I tried to fit a current photo into Hiroshige's painting.

However, this was too lonely, so I left the five-story pagoda and inserted a photo of Akabanebashi Bridge from the top of the hill, hidden by the trees.

This area has been home to human activity since ancient times, even to the extent that the Shibamaruyama burial mound still remains. In the Edo period (1603-1868), a landmark red five-story pagoda was built. However, it too was lost in the conflicts between people, and the red Tokyo Tower was built as a new landmark for Tokyo. Isn't it true that the times keep on creating and destroying new things?

Finally, please take a look at the image of Tokyo Tower. This is the view over the park next to Toshogu Shrine in the precincts of Zojoji Temple. In this park, there is a "Peace Light". This "fire" is a combination of the "Peace Light" of Hiroshima City, the "Fire of Peace" of Yame City, Fukuoka Prefecture, and the "Nagasaki Pledge Fire" of Nagasaki City. In this way, the horrors of war and the preciousness of peace are passed on to future generations.

I actually visited the 100 famous Edo views drawn by my favorite artist, Hiroshige Ando, to see how the scenes look like today.

I actually visited the 100 famous Edo views drawn by my favorite artist, Hiroshige Ando, to see how the scenes look like today.

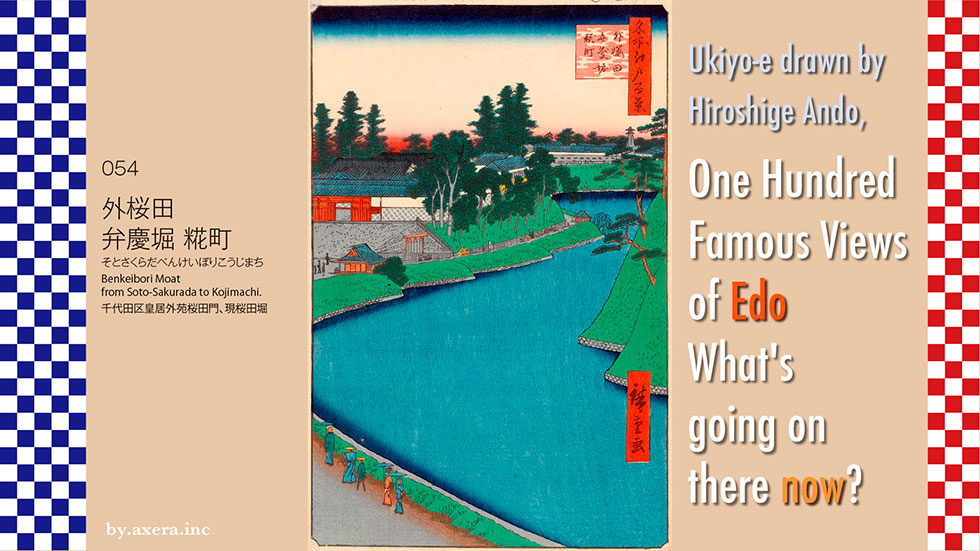

054 "Benkeibori Moat from Soto-Sakurada to Kojimachi" is a view looking toward Miyakezaka from the area across from the Metropolitan Police Department on today's Uchibori Street.

First, please check the map with the red gradation to see where this picture is viewed from. The view is from Sakuradamon Station on the Yurakucho subway line, looking toward Miyakezaka.

I put an old map of the time on top of this. As you can see from this map, there is a line of daimyo residences such as Ii, Miyake, and Matsudaira in the direction of the viewpoint. Beyond that, you can see the gray townhouses lined up along the Koshu Kaido road from Hanzomon, which is the Koji-cho area.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting. In the upper part of the picture, there is a mansion with a conspicuous red gate, which is the upper residence of the lord of the Hikone domain, Ii Kamon-no-kami. It is now the Kensei Kaikan and Kasumigaseki Park. Beyond that is the upper residence of Miyake Tosanokami, lord of the Mikawa Tawara domain. This is the area around the Supreme Court, now called "Miyake-zaka" in Hayabusacho.

The mansion with the long horizontal wall is the mansion of Matsudaira Hyobutaifu, which is now the National Theatre of Japan.

In front of the gate of the Ii family, there is the Tsuji-bansho, and next to it, where you can see three fishing pots, is a famous water well called "Sakura-no-i". On the right side of the well, by the willow tree that can be seen on the far side of the Tsuji-bansho, is another famous water well called "Yanagi-no-i".

To the right of the painting, you can see the bank of the Edo Castle lawn, which is called the Hachimaki Doi, with pine trees on top and a stone wall reinforcing the water's edge at the bottom. On the right side of the bank is the Nishinomaru, where the shogun's retired daimyo and the heir to the next shogun lived.

Although it is not visible in the picture, there is a Sakuradamon gate in front of the Benkei moat, and roughly speaking, the outer part of the moat was called Soto-sakurada and the inner part was called Uchi-sakurada.

Hiroshige depicted the Ii family's upper residence and Sakurano-i well in the near view as the Yamadaya version of Edo Meisho. Here, the common people of Edo are talking peacefully through the inner moat, heading toward the Tsuji-bansho. The Ii family's upper residence with its red gate and namako wall, and the Sakurano-i well with its three fishing pots are also well depicted.

Hiroshige also painted another cold winter scene of Soto-Sakurada. This is almost a horizontal version of Meisho Edo Hyakkei. Not many people are depicted, and it is a quiet winter scene.

Hiroshige II painted the first view looking slightly to the right, in a vertical position with the willow well at the center, in different seasons. On the left, the grass is fresh green, and on the right, you can see that the grass has turned yellow with the onset of autumn.

Hiroshige II painted the landscape slightly to the right of the one painted by Hiroshige I, in a vertical position with the willow well in the center. On the left, the grass is fresh green, and on the right, you can see that the grass has turned yellow with the onset of autumn.

Hiroshige I also painted a winter picture looking toward Sakuradamon gate over the Sakurano-i well. He depicts a man drawing water, men shoveling snow, and people coming and going in the snow with the hems of their kimonos rolled up. Although the scenery is cold, you can feel the vitality of the citizens of Edo.

I actually went to this place now. The area around the moat seems to have been preserved in its original state. The round building in the center is FM Tokyo, and to the left is the National Theater, followed by the Supreme Court.

This is a picture of Uchibori Street looking toward the Diet Building. The Metropolitan Police Department is on the left, and the current Sakurano-i well is behind the signal on the far right.

On the right is the Metropolitan Police Department, and at the end of the moat on the left is Sakuradamon gate. There are no traffic lights on the sidewalk along the inner moat, so many joggers come running by.

This is a closer shot of Sakuradamon gate. The tall, white building on the far right is the Marunouchi Building, and to the left is the Shin-Marunouchi Building. The Sakuradamon gate has recently started to be lit up at night.

This video shows the view from the entrance of Sakuradamon Station on the Yurakucho Line in the direction of the former Iyi family's upper residence, the moat, the west circle of the Imperial Palace, and Sakuradamon Gate. You can see that the pine trees on the bank, which were planted as a blindfold at that time, have grown large.

I tried to fit a current photo into Hiroshige's painting. If you match the shape of the moat, you can't see the Sakurano-i well. I haven't confirmed this yet, but it's possible that the current location of the Sakurano-i well has been moved due to the expansion of Uchibori Dori and the Metropolitan Expressway.

Still, it's amazing that the area around the Imperial Palace is still almost exactly as it was when it was built.

On a snowy day four years after this painting was published, Ii Naosuke, the owner of the Hikone domain's mansion, which is depicted most prominently in this painting, was attacked outside Sakuradamon Gate by ronin from the Mito domain, which set the era in motion.

Finally, please check the current state with Applemap's Street View.

I actually visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by my favorite artist, Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like today.

I actually visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by my favorite artist, Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like today.

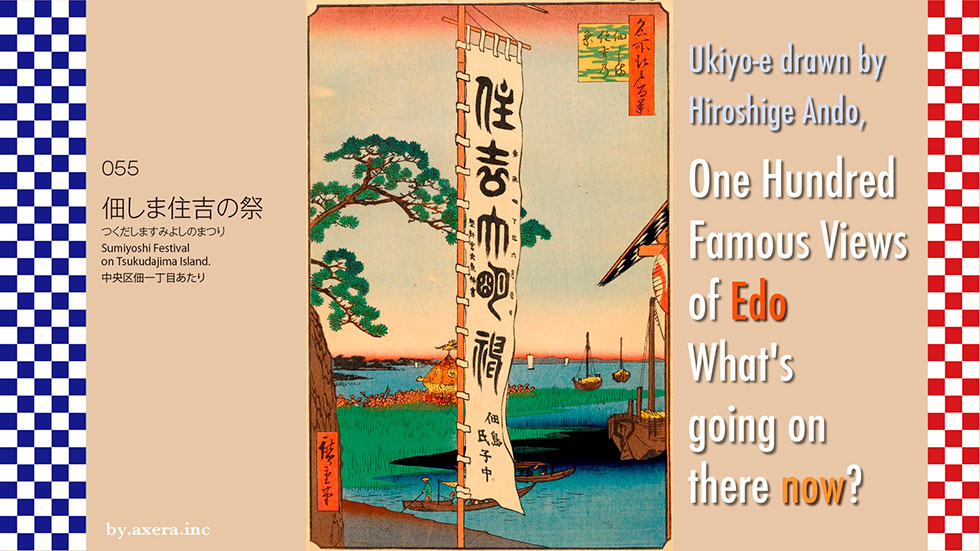

The "Sumiyoshi Festival on Tsukudajima Island" (055) depicts the main event of the festival, the parade of portable shrines at Sumiyoshi Shrine, and the large banner.

First, I used the current map to show where Hiroshige painted this picture, using a red gradation.

Here is a map of the area from 1838. You can see that Tsukuda Island was a small island.

I also superimposed a map from the 4th year of Ansei, when this painting was drawn. Tsukuda-jima and its northern neighbor, Ishikawa-jima, were islands formed on a small sandbar at the mouth of the Sumida River.

Let's go back to the current map and put a map from around 1878, which is a more accurate scale, over the top. At this time, the Ishikawa-jima area north of Tsukuda-jima was being turned into a shipyard. You can also see that the Eitaibashi Bridge was a little further upstream than it is now.

The origin of Tsukuda Island dates back to the 10th year of Tensho (1582). Ieyasu was in Sakai when he was summoned by Oda Nobunaga, and learned that Nobunaga had been defeated by Akechi Mitsuhide at Honnoji in Kyoto. From there, Ieyasu and his party of 32 decided to escape to their hometown of Mikawa.

On the way, when they reached the Kanzaki River in Settsu, they were unable to proceed due to the lack of boats to cross the river, but Magoemon Mori, the headman of the nearby Tsukuda village, and the fishermen he led showed up. The red circle on the map is today's Tsukuda Village (Tsukuda, Nishiyodogawa Ward).

Later, when Ieyasu opened the shogunate and entered Edo (now Tokyo), he invited the fishermen of Tsukuda village in Settsu, who had saved him at that time, to come to Edo and gave them the right to fish freely and the privilege of being exempted from annual tribute. The fishermen of Settsu and Tsukuda were allowed to fish freely and were exempted from paying tribute. Thirty-three fishermen and the local priest, Yoshitsugu Hiraoka Gondayu, were called to the island and named it Tsukuda Island. They also spirited away the spirits of the Sumiyoshi Shrine in Tsukuda, Settsu Province, and built the Sumiyoshi Shrine.

Let's actually take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting. The first thing that appears in the center is the large banner. These were specially permitted by the Tokugawa family to be erected during the festival, and even today, on the day of the festival, six large banners are erected.

On the left is a pine tree, and below it is a picture of a portable shrine being carried by fishermen. This is called an octagonal portable shrine, and after entering the shrine, it went out to sea and circled the island in a counterclockwise direction, and has just returned. To the right, in the distance, you can see the Shinagawa-Omori area.

Underneath, several large benzai boats float by, and to the side, the Tsukuda ferry and fishing boat are also depicted.

I tried to find a picture of Tsukuda Island as it was depicted back then. The first thing I found was an Edo Meisho Zue drawn by Saito Gesshin. It's a picture of Tsukuda Island as seen from the sky above Akashi-cho. If you look closely, you can see the green arrows and the portable shrine procession. On the lower right is the Tsukuda ferry landing.

Next is Tsukuda Island, which Hiroshige painted from the Eitaibashi Bridge in his early days. The subject of the painting is the first cuckoo, a bird that sows its seeds, so it is thought to be a view from around April. On the left is the Fukagawa Shinchi area, which is now Etchujima.

This is Tsukuda Island as seen from the Eitai Bridge. You can tell that this area was the center of the Edo harbor because there are many benzai boats in the picture. The boats go up the Nihombashi River in turn from here.

This is a panoramic view of the Eitaibashi Bridge as drawn by Hiroshige. You can clearly see the location of Tsukuda Island at the mouth of the crowded Sumida River. At that time, Eitaibashi Bridge was located a little upstream, around where IBM Japan is today. In the lower right is the mouth of the Nihonbashi River.

I actually went to this location. This is the point where Hiroshige painted this picture, seen from the south. This is the southwestern end of Ishikawa-jima Island, where there was a depot for people during the Edo period, and where the Ishikawa-jima Lighthouse was restored.

After crossing the Tsukuda Moat from the lighthouse, you will see the red torii gate on your left, and the main shrine of Sumiyoshi Shrine behind it. Today, the Sumida River is protected by high concrete walls, but in those days, from the height of this path, you could go straight down to the Sumida River.

This is the view that Hiroshige actually saw. However, there is now the Tsukuda Bridge, so I came to the bottom of it and took this photo. You can see Kachidoki on the left, Tsukiji on the right, and the Kachidoki Bridge connecting the two is small. On the right is the St. Luke's Tower. The left half of this photo is the view that was painted by Hiroshige.

This is the precincts of Sumiyoshi Shrine. It is a small shrine, but it is the guardian deity of the newly reclaimed areas of Tsukuda, Tsukishima, Kachidoki, Toyomi and Harumi.

This is the Sumiyoshi Shrine.

This is the octagonal portable shrine depicted in Hiroshige's painting. It was made by Toshihei Manya of Shiba Daimon in 1838, and has been in use for over 170 years. The inside is lacquered and waterproofed for use in the sea.

This is an octagonal portable shrine that was renewed in 2011 by Sangoro Akiyama of Hatchobori.

This is the view from the bridge over the Tsukuda Moat, looking towards the back of Sumiyoshi Shrine. The pillars for the large banner and the daki are buried in this moat and have been preserved. This method of burying them in the moat has been used since the Edo period.

The pillars and huggers that are dug out of the Tsukuda Moat during the festival are built by peeling off the three square lids of this walkway.

This is the view of the Tsukuda moat from the south. At that time, the point where the camera was located was already the sea. The skyscraper at the back of the building was a stopping place for people during the Edo period, then became the Ishikawajima shipyard, and was reborn as the Okawabata River City in a redevelopment project initiated by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government.

This is the view of Tsukuda Island from where the ferry used to be on the Akashi-cho side. Behind the red torii gate is Sumiyoshi Shrine, the sluice gate on the left is the Tsukuda moat, and to the left is the rebuilt Ishikawa-jima lighthouse, which was Hiroshige's viewpoint. The octagonal portable shrine will be taken out of Sumiyoshi Shrine, pass through the red torii gate in front, and enter the sea. It then goes to the right, circles the island from the southern tip of Tsukuda Island, and comes back here to land. That's when Hiroshige drew this picture from the lighthouse area.

Until the Tsukuda Bridge was built in August 1964, the year of the Tokyo Olympics, people commuting to the shipyard and the residents would make as many as 70 round trips a day from here to Tsukuda Island.

This is a photo from the beginning of the Taisho era (1918-1926), which was published in a book titled "One hundred views of Edo in contrast to the past. The scene seems to be that the portable shrine has entered the sea from the shrine and the portable shrine procession is about to begin. You can clearly see that it was an octagonal mikoshi (portable shrine) even then.

I tried to fit Hiroshige's painting with an actual photo of the area today. Skyscrapers in front of Kachidoki Station stand in the area that was once the sea. The Tsukiji fish market, which used to be on the right of this picture, has now been moved to the landfill site of Shin-Toyosu, far to the left of this picture.

Edo Bay has been continuously reclaimed since Ieyasu's arrival in Japan, and will continue to be so for many years to come.

I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by my favorite artist, Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like today.

I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by my favorite artist, Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like today.

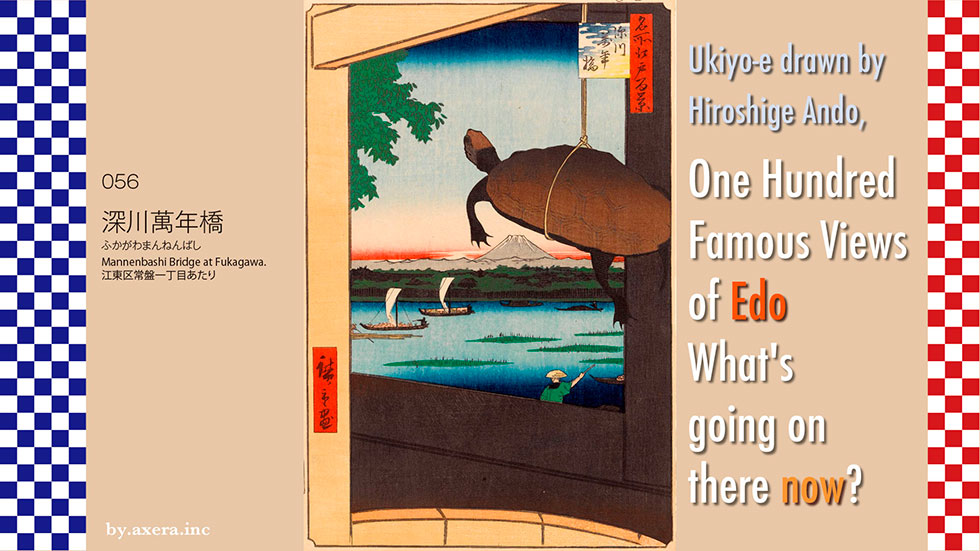

"056, Mannenbashi Bridge at Fukagawa", Fuji over the Mannenbashi Bridge in Fukagawa, with a turtle in the foreground.

Fuji in the foreground. Hiroshige seems to have been troubled by this painting of Mt. Fuji, but first, please check the wide area map of Applemap to see where this place is.

Hiroshige's viewpoint is shown in red gradation. The Mannenbashi Bridge was located to the west of Edo Castle, around the intersection of the Onagigawa River, which flows in a straight line from the east into the longitudinal Sumida River.

The Onagi River is now divided by the Arakawa River, but at that time it was connected to the Gyotoku, and was an important river for transporting salt and vegetables from the Gyotoku area to Edo City. This is a man-made river, or canal, built by Ieyasu Tokugawa after he came to Edo, so it is almost a straight line.

Please see a more detailed map. At that time, the Mannenbashi Bridge was a bit closer to the Sumida River, and was raised in the shape of a drum so as not to obstruct the passage of boats sailing underneath. The view of Mt. Fuji over the Sumida River from there was so beautiful that it became a famous landmark.

I combined and covered this with an old map from the Tenpo period. In the direction of the viewpoint, on the other side of the Sumida River, there is the residence of Nagatono-kami Ando, a member of the Iwaki Taira clan in Mutsu Province. You can also see that the Shin Ohashi Bridge was built much further downstream than it is now.

I covered the map with a more accurately scaled map from the Meiji era. You can see that the Sumida River in the direction of the viewpoint makes a big turn and widens in this area. There is a place surrounded by a blue dotted line with the word "reed" written on it. This place was called "Mitsumata parting pool" because the sand from the Sumida River tends to accumulate here and the salt water and fresh water separate at high tide.

In 1772, this sandbar was reclaimed and a new area of 9,600 tsubo called Tominaga-cho was built, and it became a pleasure quarter along with Ryogoku. However, 17 years later, under the Kansei Reforms, the area was returned to a reed-grown sandbar, and Hiroshige called it "Nakasu now, the dream site of fools" in his poem "Karuta.

Now let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

At first glance, it is hard to tell what the painting is about, but the yellow area around the turtle is the wooden bucket in which it is suspended, and the brown area inside it is the parapet of the Mannenbashi Bridge. There are probably a few more turtles in this wooden bucket, although they are not visible.

In fact, this painting depicts a scene from the Houjo-e festival. Hojoe is a religious ritual in which captured fish, birds, and animals are released into the wild to discourage killing. In Japan, it was adopted into Shintoism through the syncretism of Shintoism and spread throughout the country.

This is the Dai Nihon Meishoukan (Great Japanese Reader of Generals) by Tsukioka Honen, which depicts Minamoto no Yoritomo releasing 1,000 cranes on Yuigahama beach during a releasing ceremony at Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine.

During the Edo period (1603-1868), the "Houjoe" festival was held at shrines and temples all over Japan on August 15th to release captured birds and fish into the mountains and rivers to pray for the souls of the dead and for one's own future life.

A customer buys a turtle from the turtle shop, releases it into the river, and the turtle shop catches it again and sells it to a new customer, a very relaxed way of doing business. Hiroshige painted this picture with a bold composition of the turtle shop's barrels, the turtles, and the view of the Sumida River and Mount Fuji over the parapet of the Mannenbashi Bridge.

In the center of the painting is a stone turtle with Mount Fuji below it and Takase boats and rafts floating on the Sumida River. The sandbar with green reeds in the river is the "Mitsumata parting pool" which was an entertainment district for 17 years.

The reason Hiroshige went to the trouble of painting the Bannen-bashi Bridge, when the famous Houjo-e at Tomioka Hachimangu Shrine in Fukagawa is the most famous, is that he wanted to compete with the cranes painted by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi. In Japan, it is said that a crane lives for a thousand years and a turtle for ten thousand. Furthermore, it is said that the Mannenbashi Bridge was named after the Eitaibashi Bridge that already existed in Japan, where "Eitai" means eternity.

This is the 36 Views of Mount Fuji by Katsushika Hokusai, a senior painter to Hiroshige and famous for his Mt. The roundness of the Mannenbashi Bridge is exaggerated in the painting, and the people are vividly depicted to give a glimpse of life at that time. The contrast of Edo commoners leisurely dropping fishing lines beside a boat coming from Gyotoku creates a very tranquil atmosphere for Mt.Fuji.

When Hiroshige painted "Mannenbashi Bridge at Fukagawa" he must have been conscious of his senior and rival Hokusai.

I actually went to this place. This is the view from the current Mannenbashi Bridge.

Moving a little closer to the Sumida River, this is the view from the area where the Mannenbashi Bridge used to be. The bridge on the left is the Kiyosubashi Bridge, the building in the back is the Yomiuri Shimbun, and the building on the right is the Tornare Nihonbashi Hamacho, a high-rise building built on the Hamacho Nakano-hashi cross.

This is a picture of the Mannenbashi Bridge from the north. It has moved a little further east than it was then, and is now a magnificent steel-framed bridge.

This is the Masaki Inari Shrine, which was located at the foot of the Mannenbashi Bridge to the north at that time. It was believed to have the power to heal boils, and was a popular place of worship. At that time, there was a large Masaki tree beside the shrine, which served as a landmark for boatmen at the entrance to the Onagi River. Just beside this area, Matsuo Basho lived in a hermitage until he left for the "Narrow Road to the Deep North. There is now a Basho Memorial Museum nearby.

Please look at the painting again. This painting is said to have been painted in November 1857. Hiroshige passed away less than a year later.

In 1853, the arrival of the Black Ships from America caused an uproar that turned all of Japan upside down. Two years later, the Great Ansei Earthquake struck, and by the time this painting was painted, the citizens of Edo were finally beginning to regain their peaceful lives. However, the times were on the verge of being swallowed up by the new wave that was steadily coming in.

This painting shows a tortoise at a releasing party that brings merit, and over the parapet of the Mannenbashi Bridge, the "Mitsumata parting pool," now in the water after its prosperity. In the background is the eternal sacred mountain Fuji and the quietly flowing Sumida River.

Hiroshige was depicting here a kind of "flow of time" that transcends time and space, quite different from the Fuji depicted by Hokusai.

I tried to fit the current scenery into Hiroshige's painting. However, this was not enough to create a picture, so I removed the parapet of the bridge. What do you think?

Coincidentally, doesn't the arch of the Kiyosubashi Bridge look like Mt. Fuji. It also looks like Hiroshige worshipping the gods with his hands.Isn't it possible to see the eternity of peaceful Edo that Hiroshige was hoping for?

I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Ando Hiroshige, a favorite of mine, to see how the scenes look now.

I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Ando Hiroshige, a favorite of mine, to see how the scenes look now.

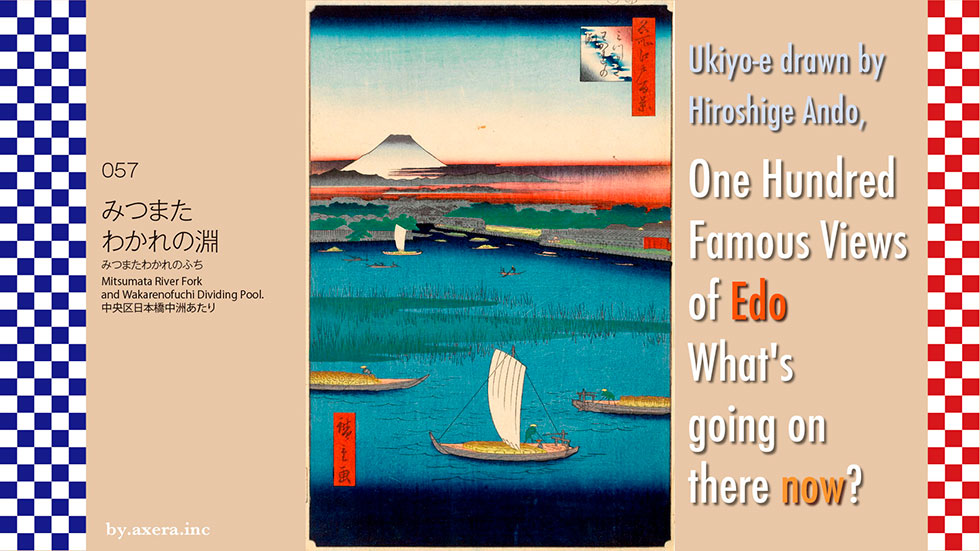

057 "Mitsumata River Fork and Wakarenofuchi Dividing Pool." is a view from the Kiyosubashi Bridge over the Sumida River, looking toward the Hakozaki Junction of the Tokyo Metropolitan Expressway.

Please check the Applemap to see where this place is located, right next to the Mannen Bridge mentioned in 056.

I enlarged the map a little more and added a red gradation to the places where Hiroshige's viewpoint would have been. I inserted an old map of the time into this. Please forgive the fact that the left bank side, the Fukagawa direction, is completely off because the map of that time is quite distorted.

I have included the places depicted in the painting in this map. The subject of the painting, the "Mitsumata River Fork" is depicted as a green sandbar with reeds growing in the Sumida River.

A large town once existed on this sandbar. In 1771, a sandbank in the Sumida River was reclaimed, and in the following year, a new area of 9,600 tsubo was created, named Tominaga-cho, which was a continuation of Hamacho. Three years later, 93 restaurants, bathhouses, and other establishments lined the area, making it an entertainment district on par with Ryogoku. The reclaimed land at that time is shown by the yellow-green dotted line.

However, because the Hakozaki River, a branch of the Sumida River shown on the map, was closed, flooding occurred frequently. 17 years later, during the Kansei Reforms, the area was returned to the original sandbar and the Hakozaki River was reclaimed as a waterway. Hiroshige painted the sandbank again 68 years later.

Let's take a look at Hiroshige's painting based on this map. First, there is a fairly large summer scene of Mt. Fuji in summer. Below it is the Eietai Bridge over the Hakozaki River, and at the entrance to the Hakozaki River are the residences of the Tayasu Tokugawa family on the left and the Shimizu Tokugawa family on the right. While the Tayasu family is clearly painted, the Shimizu family is painted in some kind of yellow.

To the right, across the Kawaguchi Bridge, the residence with the red gate is the subordinate residence of Nagatono-kami Ando, a member of the Iwaki Taira clan in Mutsu Province. Perhaps because the Hakozaki River has been re-dug, the sandbar has been moved to the middle of the Sumida River. It seems that this area is the sandy point of the Sumida River. In front of the sandy sandy beach, medium-sized boats such as tea boats and Takase boats are sailing on the Teppozu and the Umaya riverbank upstream, carrying cargo transshipped from big Kaisen boats.

In the Edo period, the "three families" were Owari, Kii, and Mito, but there were also the "three lords". In addition to the three families, there were also the "Three Lords," which were established to produce heirs to the shogunate, but they were like the reserve of the three families. In a sense, they were the underpinnings of the succession production system: the Tayasu Tokugawa family, the Hitotsubashi Tokugawa family, and the Shimizu Tokugawa family. This time, Hiroshige's painting depicts the subordinate residences of both the Tayasu and Shimizu families.

The Shimizu Tokugawa family was founded by Shigeyoshi, the second son of Ieshige, the ninth shogun of the Edo shogunate, and had produced several lords of the Kishu domain. For 20 years from 1846, it was called Akeyakata without a head. Hiroshige painted this picture in 1857, exactly ten years after the head of the family was absent. The yellow area in this painting is the Shimizumis' the lower residence, or villa, and I believe it was vacant land.

After that, the Shimizu family welcomed the 6th head of the family, Akitake (adopted from the Mito Tokugawa family, younger brother of the 15th shogun, Yoshinobu), in 1866, but he succeeded the Mito Tokugawa family as the 11th head of the Mito domain two years later, and the Meiji Restoration came without a head of the family.

I looked for Ukiyoe paintings that depict this area. First of all, here is a painting by Hiroshige looking at the area from the Hakozaki River. The red gate on the left is the upper residence of the Ando family, and on the right is the Shin-Ohashi Bridge. The sandbar is drawn quite large. By this time, the sand had accumulated and the sandbar was getting bigger and bigger.

This is a painting of the Eitai Bridge from the upper residence of the Ando family to the right of the lower residence of the Tayasu family. At the end of the dense sandbar, you can see that the houses are densely packed in Fukagawa. The boats with their sails up now have their sails down and sail poles bent when they pass under the bridge.

This is a view of the Hakozaki River from under the New Bridge. The red gate on the right is the Ando family's upper residence, and beyond that is Kawaguchi Bridge. The lower residence of the Shimizu Tokugawa family is depicted as a grove of trees. Fuji is depicted in the same position, which means it must have actually looked like this.

Eisen painted a picture seen from around Kawaguchi Bridge. On the right of the center is the lower residence of the Tayasu Tokugawa family, the Eitaibashi Bridge can be seen across the Hakozaki River, and the white residence to the right is the middle residence of Sadono-kami Makino of the Tanabe clan in Tango Province. For some reason, this painting does not show a sandbar.

This is a painting by Hiroshige and Shosai Ikkei, probably painted from the Shin-Ohashi Bridge. The angle of the two paintings is almost the same, but the way the sandbank is depicted is different. Hiroshige depicts fishermen raising their boats on the sandy beach, while Shosai Ikkei depicts women and children on a boating trip. It is interesting to note that the shape of the seawall of the Tanasu Tokugawa family's suburban residence is almost the same. Beyond the Eitaibashi Bridge, many sailing poles of circumnavigations coming into the Teppozu harbor are depicted.

I actually went to this place.

The gate-shaped building on the left, in front of the Metropolitan Expressway, is the River Gate Building, and the area to the right of it is where the current address is Nihonbashi Hakozaki-cho, Chuo-ku. The blue sign is the Hakozaki Pumping Station, and the area to the right is where the Tayasu Tokugawa House was located on the map. The brown apartment building to the right and the white apartment building to the right of it are around the reed-grown sandbar in the picture.

This is the present-day Kiyosubashi Bridge as seen from the Nakasu side looking toward Fukagawa. Hiroshige's painting is the view from the middle of the bridge, looking to the right and west-southwest.

This is the view from the base of the Kiyosubashi Bridge, looking towards the right bank of the Sumida River. The bank is a promenade called Sumida River Terrace. In the foreground on the right is what is now the address of Nihonbashi Nakasu in Chuo Ward. There used to be a sandbar on the right here, but the Hakozaki River has all been reclaimed and is no longer there.

Please look at the painting again.

In the painting, the Shimizu Tokugawa family, which is depicted in a strange yellow color, is thought to be the current location of Arima Elementary School in Chuo Ward. When I looked up the three lords and the Shimizu Tokugawa family, I felt a little sad. I also felt a sense of sadness when I learned that the reed-filled sandbar in the Sumida River is a remnant of Tominaga-cho, a very lively entertainment district 68 years ago. Did Hiroshige deliberately paint the location of the Shimizu family in a conspicuous yellow color in order to create such a sense of sadness?

I tried to fit the current view into Hiroshige's painting. However, it has become a picture of an apartment building standing on the original sandbar.

So I combined Applemap's street view and Mt. Fuji in summer to create a modern look. The highway is the old Hakozaki River, and the area around the turn to the right is the Nihonbashi River. The apartment buildings in the lower right are the river and the sandbar. It's interesting to look at it this way. Fuji does not look this big in reality.

I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando, a favorite of mine, to see what the scenes look like today.

I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando, a favorite of mine, to see what the scenes look like today.

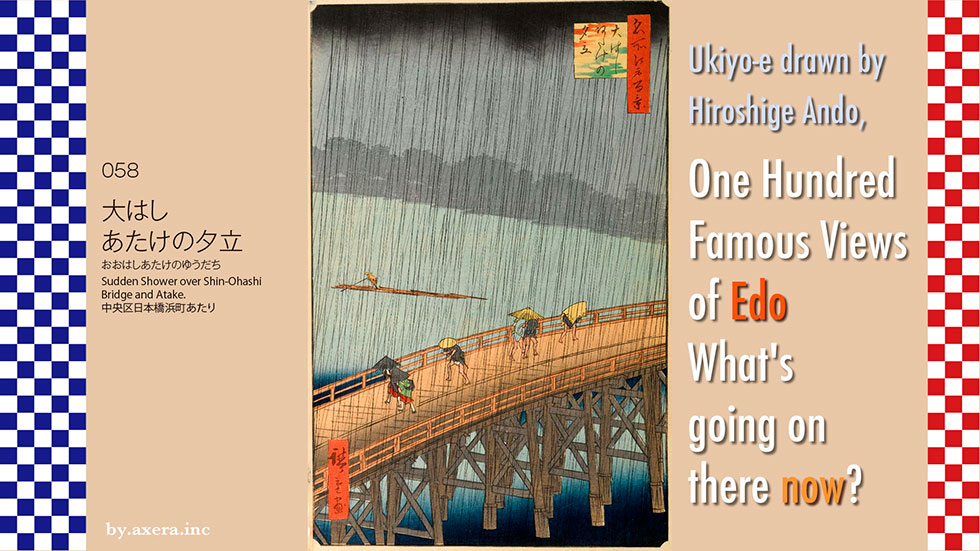

058 "Sudden Shower over Shin-Ohashi Bridge and Atake" is a view of the Shin-Ohashi Bridge from the direction of Hamacho in the Edo period, when the bridge was located downstream from the current Shin-Ohashi Bridge.

Please check the map to see where this painting was drawn from. It is a drawing of the Edo-era Shin-Ohashi Bridge, which was built just where the Sumida River turns west, looking north.

I put an old map of that time on top of this one. You can see that the Shin-Ohashi Bridge was built much farther south than it is now.

The Shin-Ohashi Bridge was built in the winter of 1693, the third bridge along the Sumida River, and was named "Shin-Ohashi" to follow the Ryogoku Bridge, which was called "Ohashi. It is said that Keishoin, the mother of Tsunayoshi Tokugawa, the fifth shogun of the Edo shogunate, built the bridge for the citizens of Edo, who were forced to live in inconvenience due to the lack of bridges.

Matsuo Basho, who lived at the foot of the Shin-Ohashi Bridge to the east at the time, wrote a haiku about the completion of the bridge.

"On the bridge where the first snow is falling.

"Thank you, you made it and stepped on the frost on the bridge.

As you can see from the map, the Shin-Ohashi Bridge was located in a fast-flowing area and was repeatedly damaged, washed out, and burned down more than 20 times. During the Kyoho era, when the shogunate's finances were in dire straits, the government gave up on maintaining the bridge and decided to demolish it, but the bridge was allowed to continue to exist on the condition that the town would bear all the expenses associated with maintaining it.

However, the bridge was allowed to continue on the condition that the townspeople would bear all the expenses associated with maintaining the bridge. The townspeople collected donations and set up rules such as those for people to cross the bridge without resting to prevent damage, merchants and beggars were not allowed to stay, and carts were not allowed.

In the direction of the viewpoint, around the base of the current Shin-Ohashi Bridge, there is a place labeled "Mifunakura". This was the place where the Shogunate's boats were kept at the time.

The Atake Maru, a military-style goza-bune warship newly built by Iemitsu Tokugawa, the third shogun of the Edo Shogunate, was completed in 1634 in Ito, Izu. After that, it was moored in the Gofunagura (warship warehouse) here in Fukagawa, and was decorated in a luxurious and ornate manner without ever being used in battle. The ship was 38 meters long, 20 meters wide at the shoulders, and drained 1,500 tons of water, so it was probably too large to be useful. In the peaceful Edo period, the ship fell into decay and was dismantled without ever being used. The area around the ship came to be called "Atake" after the Atake Maru.

Looking at a map from the Meiji era, we can see that there was a ferry called "Atake no Ferry" that went to and from the banks of the Atake ports, and it seems to have been very prosperous.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

First, at the top of the painting, there are some suspicious rain clouds in black. The distant view is hazy due to the rain, and the gazebo and fire watchtower are painted in pale gray. It is interesting to note that the riverbank and the rain streaks are slightly tilted, as if the photo was taken in a hurry, and the composition is zigzagged with the bridge.

In this downpour, the rafts that must have been carrying the lumber from upstream were moving slowly along the Sumida River, and the common people crossing the bridge were not in a hurry, but were slowly trying to cross the bridge.

Paris, 1886. Van Gogh, an unsuccessful 33-year-old painter who was looking for a new style of painting, happened to see Ukiyo-e painted on paper wrapped to protect ceramics sent from the Orient. Later, he saw more Ukiyo-e at an art gallery and tried to copy some of them. This is one of them.

Hiroshige, who died in 1858, could not have imagined that more than twenty years after his death, in Paris, Van Gogh, the master of Impressionism who would later become famous, would be copying his painting. Van Gogh also committed suicide as an unsuccessful artist three years after painting this picture.

I actually went to the location of this painting.

This is a picture of the current New Bridge from a similar direction. It's a little different in terms of the height of the viewpoint and where you are looking.

This is a picture of the back of Hiroshige's painting, looking upstream at "Atake". The area where the scaffolding for construction is now is where the Mifunagura used to be.

This is a photo of Hiroshige's point of view from the other side of the river. It is thought that he was looking at this from the sky above the building with the yellow sign on it.

I actually tried to fit the current photo into Hiroshige's painting. It's an obvious picture, isn't it?

This doesn't give a unique zigzag composition, so I relied on the street view from Applemap. I also tried to make it rain.

But after all, the perfection of Hiroshige's painting is astounding.

The remnants of the warship Atake Maru, left to decay as a result of the continued peaceful era. A quiet and peaceful scene of townspeople and rafts crossing a bridge for the common people of Edo. The downpour of rain from the black clouds falling there. And the tilted composition. This painting, said to be Hiroshige's masterpiece, may have been depicting a time when peace would be broken and bent in the future.

I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by my favorite artist, Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like today.

I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by my favorite artist, Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like today.

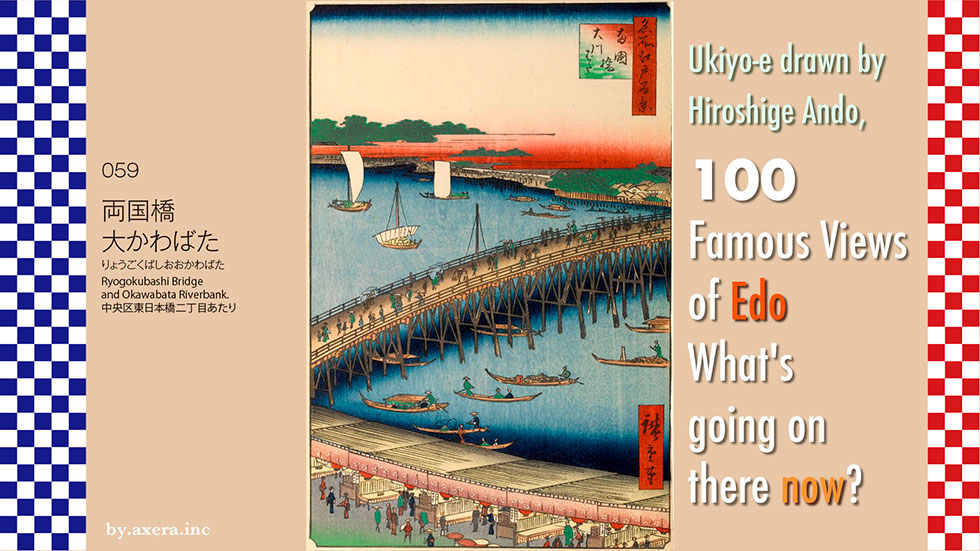

059, "Ryogokubashi Bridge and Okawabata Riverbank," is a view of the bridge from the west side of Ryogoku-bashi Bridge, looking over Ryogoku Hirokoji, which was a fire protection area at that time.

Please check Hiroshige's viewpoint on the map. It is shown in red gradation.

The scale and position are a little off, but here is an old map of the time overlaid on top.

At that time, Ryogoku Bridge was about 20 meters downstream from its present location.

There are two theories as to when the bridge was built, 1659 or 1661. The Edo Shogunate did not allow bridges over the Sumida River except for the Senju Bridge on the Nikko Kaido Road, because of the need for protection. However, in 1657, during the Great Fire of Meireki, the largest fire of the Edo period, many Edo citizens who had no bridges and no place to escape were swept away by the fire, resulting in more than 100,000 casualties.

The shogunate took this situation very seriously and finally decided to build a bridge at this location. About 70 years after the Senju Bridge, the second bridge, the Ryogoku Bridge, was finally built over the Sumida River. This marked a major shift by the shogunate in Edo's urban planning from a defensive strategy to an urban planning for the citizens. The Ryogoku Bridge is a product of peace. The bridge is shown on an old map in yellow, somewhat thickly.

Here is a series of ukiyoe related to Ryogoku Bridge from Hiroshige's three series of wide depictions of the bridge.

At first, the bridge was called Ohashi, but since it straddled two countries, Musashi in the west and Shimousa in the east, it was popularly called Ryogoku Bridge, and when the new Ohashi Bridge was built in 1693, it became the official name.

Since the Ryogoku Bridge was built, two major events have taken place.

The first was the bustle of the fire exclusion areas on the east and west sides of the bridge, which were built to prevent the spread of fire. The west side in particular, called Ryogoku Hirokoji, was lined with restaurants and teahouses, many of which were covered with reed screens, as well as theatrical performances, lectures, circuses, and other spectacles. However, the stores were limited to those with simple construction so that they could be demolished immediately to prevent the spread of fire in the event of a fire.

The other was the development of the towns of Honjo and Fukagawa, where many Edo citizens lived. In those days, the main street to access the north was the Oshu Kaido, which left Nihonbashi and crossed the Kanda River at Asakusa Gomon to head north. After the Ryogoku Bridge was built, you could choose to walk across the Sumida River here first, pass by the birthplace of sumo, Eko-in, and then head north toward Boso and the north.

In 1732, the Ryogoku Fireworks Festival was held to celebrate the opening of the river, and the towns of Honjo and Fukagawa grew even more. The fireworks were depicted in many Ukiyoe prints around this time, and became very popular.

Here you can also see a very clear Ryogoku Bridge painted by Katsushika Hokusai, Hiroshige's rival. This painting is a view of Ryogoku Bridge and Mt. Fuji from upstream, in the opposite direction of Hiroshige's painting.

Here is a photo of the Ryogoku Bridge area published in the Meiji era. Ryogoku Bridge continued to develop as an important bridge connecting Edo (Tokyo) and Boso (Chiba) and as a place for leisure after the Meiji era. However, Ryogoku Bridge, which was made of wood, was replaced many times since the Edo period due to spills, burns, and damages, and in 1875, it became a huge wooden bridge 175 meters long in the western style.

On August 10, 1897, during a fireworks display, the bridge was pushed down 10 meters by a crowd of people trying to avoid the fireworks sparks that landed on the bridge, resulting in a catastrophic collapse of the parapet and dozens of casualties.

As a result, it was reborn in 1904 as an iron bridge with triple arches, 164.5m long and 24.5m wide.

Now, let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

First of all, the area hidden by the red hazy clouds at the top is a Shogunate facility called the Mitakegura. It is a place where building materials are stored for disasters, and boats can enter and exit from the Mikura Bridge on the left. This is the current location of Ryogoku Station and the Kuramae Kokugikan.

As was customary when depicting shogunate facilities, publishers would cover them with hazy clouds to hide the contents and prevent them from being banned.

To the right, on the bank of the river at Yokonami-cho, you can see a seawall facility called "Hyappon piles" to protect against waves. The area behind this was used as samurai residences at the time.

Below it, the Sumida River flows from left to right, and the surface of the river is covered with many different types of ships, including noryo boats, takase boats, boar boats, tea boats, and fishing boats. The Ryogoku Bridge over the river is crossed by many people of various occupations. You can feel the peacefulness of the time flowing by.

The bottom of the picture is a raised area called Ryogoku Hirokoji in Okawabata. You can see that many of the stores are covered with reed screens. The Sumida River was called the Asakusa River or the Miyato River around Asakusa, and the area from Ryogoku Bridge to Shin-Ohashi was generally called the Okawa River, and the west bank of the river was called the Okawabata.

I actually went to this place.

Please take a look at the photos taken from the same area continuously since the Meiji era. The angle is a little low, but this is approximately where Hiroshige painted it. The current Ryogoku Bridge has no arches, and what you see in the photo is the overlapping arches of the JR railroad bridge.

From the point of view Hiroshige would have painted it, turn the camera 360 degrees to the left.

I tried to fit the current photo into Hiroshige's painting. The picture has a completely different atmosphere.

In addition, I tried to use the street view from Applemap to create an atmosphere, but it also turned out to be a terrible composition. Sorry about that.

Originally, the Ryogoku Bridge was built to save people from fires during the Edo period. Later, in the Meiji era, accidents occurred and many people died, so the bridge was replaced with an iron bridge. However, in the Showa era, 87 years after Hiroshige painted this picture, the city was burned to the ground, leaving only the iron bridge.

This photo was taken by the U.S. Army right after the Great Tokyo Air Raid (firebombing of Tokyo, Mar. 10, 1945). The bridge that looks like a bone in the upper right corner is Ryogoku Bridge, and above it is the Shin-Ohashi Bridge. I wonder where Hiroshige made the mistake of going in this direction from the peaceful world he depicted.

I think we all need to rethink this as we look at the peaceful Ryogoku Bridge painted by Hiroshige. While listening to John Lennon's Imagine.

I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by my favorite artist, Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like today.

I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by my favorite artist, Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like today.

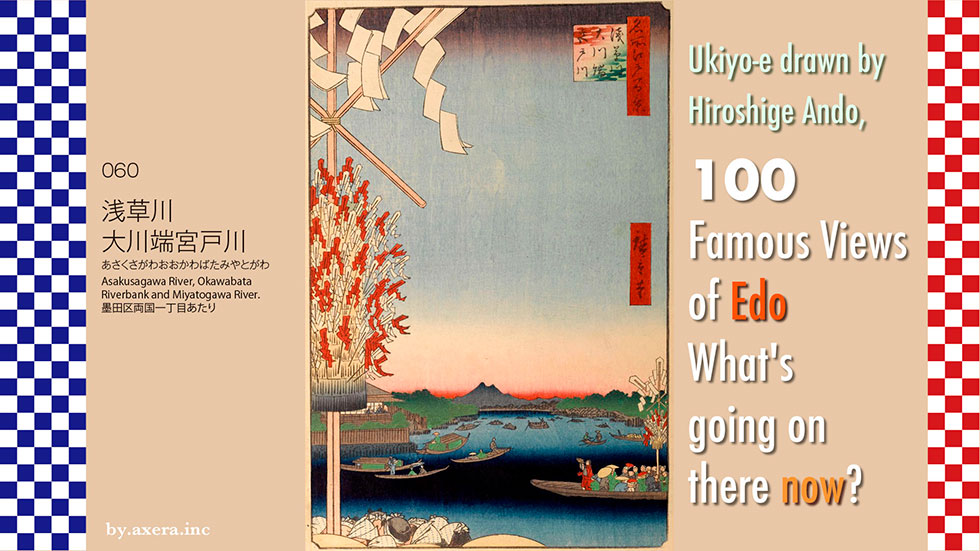

The picture "Asakusagawa River, Okawabata Riverbank and Miyatogawa River" 060 is a view looking north-northeast, upstream from Ryogokubashi Bridge on the Sumida River at that time.

First of all, please visit Applemap to see Hiroshige's point of view.

I put a map of the time on top of this. Ryogokubashi Bridge was about 20 meters downstream from its present location. To the north of the west end of Ryogoku Bridge was the Yanagibashi Bridge, which crossed the Kanda River, and across the bridge was a famous restaurant called Manpachiro. The building depicted in the lower left of Hiroshige's painting is the Manpachiro.

Please take a look at an old map with a wider area. I added Hiroshige's point of view in red gradation. At that time, you could see all the way from Ryogokubashi Bridge to Azumabashi Bridge.

At that time, the Arakawa River was called the Sumida River downstream from the Senjuohashi Bridge. Around Asakusa, it was also called the Asakusa River, or the Miyatogawa River, because of the appearance of the statue of Kannon, the principal deity of the Sensoji Temple. From here on, the river was called the Okawa, and the west bank from Ryogokubashi Bridge downstream to Reiganjima was called Okawabata.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

The main subject of this article is a group of people visiting Mt. Oyama is the main peak of the Kanagawa Tanzawa system. Here, a priest named Roben built the Sekisonsha Shrine to enshrine Seison Dai-Gongen, Fudo Hall to enshrine Fudo Myoo on the mountainside, and twelve lodging houses around it.

Mt. Oyama was originally a mountain of worship for farmers, also called "Rainfall Mountain. From around the middle of the Edo period, it became popular for people to form Oyama-kō, like the Fuji-kō, to pay homage to the mountain, as it was believed to be beneficial for gambling and business.The boom was triggered by the fact that compared to the Fuji-kō, Oyama was much easier to reach.

The large image on the left side of Hiroshige's painting is called Bonten (Brahma-Deva), which was distributed to each house in the town after the Oyama pilgrimage. At the east end of Ryogokubashi Bridge, there was a place for purification, and after purifying oneself, the leader of the group, dressed as a mountain priest, blew a Buddhist shofar while carrying a wooden sword to dedicate to the god. They all repeat in unison, "Repentance, repentance, purification of the six roots," as they proceed. In Hiroshige's painting, the group on the right crosses the river by boat, while the group on the lower left walks across Ryogokubashi Bridge.

I looked for traces of the Oyama pilgrimage that was popular at the time. This is Totsuka in Hiroshige's 53 Stages of the Tokaido Road. On the left side, the signboard of "Komeya" has a tag of "Oyama-ko-chu" hanging on it, which indicates that this was a regular lodging for Oyama-ko.

In Fujisawa in the same 53 stage of the Tokaido Road, a group of people walking down the slope of Yugyoji Temple are depicted with wooden swords and the same appearance.

In Hiratsuka in the 53rd Meisho Zu-e (Famous Places in 53 Stages), Mt. Oyama is depicted in large scale at the end of the Banyu River. The painting on the left is titled "People visiting Oyama on the road" and depicts people with wooden swords, people carrying portable shrines to offer sacred sake called Miki-waku, and touts at inns soliciting them. The route from Hodogaya to Oyama is also drawn at the top.

In the painting on the right, Hiroshige has also included five other places of interest along the Oyama road in one painting. It is interesting that he even depicts Koyasu's souvenirs.

In the painting on the left, Katsushika Hokusai dynamically depicts "Roben no Taki," the goal of the Oyama pilgrimage. In the lower right corner, a lodging house with the name "Taki no Bo" written on it is also depicted.

This is what Oyama looks like today as seen from Sagamihara.

While researching photos, I found one with almost the same angle as Hiroshige's viewpoint. It was taken during the Meiji era (1868-1912), and although it is a snowy scene, the building on the left is the Manpachiro that Hiroshige painted. To the left is the willow bridge.

Hiroshige painted the view from the Manpachiro to the other side of the river.

This is a picture of Ryogokubashi Bridge over the mouth of the Kanda River, probably taken from the Manpachiro.

Here is a photo actually taken from what would have been Hiroshige's point of view. The Ryogokubashi Bridge and the light green arches are JR railroad bridges. Of course, Azumabashi Bridge is not visible, nor is Mount Tsukuba at this height. The golden building on the far right, beyond the Metropolitan Expressway, is the Sumida Ward Office at the east end of Azumabashi Bridge.

I tried to fit the current photo into Hiroshige's painting. What do you think?

According to my research, before Hiroshige painted this picture, the pilgrimage to Oyama had temporarily gone into decline. The Shogunate was alarmed by the military might of the monks and shugenja, as well as the spread of the flamboyant lectures, and in 1842, the "Miki-wake", which was shown in the painting, was banned. However, it became so popular that in 1857, a caricature book titled "Oyama Dōchū Hizakurige" was published, and as shown in the painting, Edo artisans, mainly carpenters, steeplejackers, and plasterers, headed for Oyama.

Hiroshige depicted the city of Edo and the common people who had completely recovered after the earthquake.