I visited my favorite "Meisho Edo hyakkei" (One hundred Famous Views of Edo) painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what those scenes look like today.

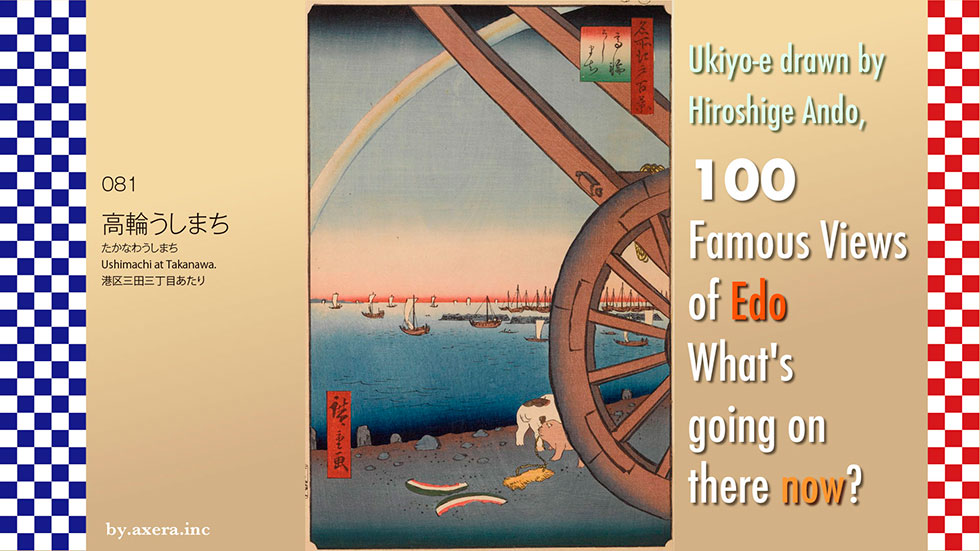

Ushimachi at Takanawa" (081) is a view looking toward the sea from the Sengakuji Subway Station, about where it is today, over a large carriage. At the time of Hiroshige, there was nothing on the east side of the Tokaido but the ocean.

First, please check Applemap to see where this picture was painted.

The earthen mound of Takanawa-Okido still remains on the north side of Sengakuji Subway Station, and Hiroshige seems to have painted the view of the sea from a little south of this Okido. We have used a red gradation to indicate the location from which Hiroshige's viewpoint was probably taken.

I put a picture map of those days over this. You can see that the east side of Tokaido was immediately lapped by the waves with no houses.

Let's put a map of the early Meiji period on top of this map. In this map, we can already see that the earthwork for the railroad has already been built beyond the coastline.

Let's reduce the size of this map, this time to a wider area. A diamond-shaped island-like structure appears in the sea to the east. These are so-called "platforms," or gun batteries for maritime defense, which the Edo Shogunate hurriedly built in response to the appearance of the black ships from U.S. The sixth and third gun batteries on the right still exist in Odaiba.

The coastline from Tamachi to around Shinagawa, which forms a slow arc, was called Takanawa, and was also famous for its moon.

Now, please take a look at the Takanawa zenzu, a bird's eye view of this area drawn by Hiroshige from the north.

The arch of the coastline is a bit exaggerated, but you can get the general atmosphere of the area. I also added Hiroshige's viewpoint in red gradation.

The "Ushimachi" that Hiroshige depicted is on the right side of the street to the south of Takanawa Okido, officially known as Shibakuruma-cho. In the lower left corner of this painting, around the stone wall of Okido, you can also see small oxcarts and large eight-wheeled carts.

For the construction of Zojoji Ankoku-den in 1634 and the building of the stone wall at Ichigaya-mitsuke two years later, a large number of oxcarts capable of transporting heavy items were needed. The Shogunate therefore called in oxen carriers, led by Seibei Kimura, an ox dealer in Kurumacho, Shijo, Kyoto, to Edo to transport the oxen. After the construction work was completed, they were allowed to settle down in this town and as a reward, were granted exclusive rights to use ox-drawn carts to transport goods, and the group of ox-drawn cart specialists continued to grow. At its peak, there were about 1,000 head of cattle in this area, which was officially called Kurumacho, or "cattle town.

As time progressed, when the number of cattle decreased due to the spread of an epidemic, Hachizaemon, a wheelwright from Kurumacho, developed the "Daihachi-guruma," a vehicle pulled by eight people instead of oxen. With this invention, however, oxen were no longer needed and the demand for ox carts themselves began to decline rapidly.

Sengakuji Temple, made famous by the Chushingura story, is depicted on the right in the middle of the painting. A little further on is the residence of the Arima family of the Chikugo Kurume domain. This location is now the Shinagawa Prince Hotel.

The Shinagawa-juku is depicted much further ahead, but it is not the current Shinagawa Station, and the Shinagawa-juku begins beyond that point, beyond Gotenyama.

At the back of the Arima family's villa, the Shogunate's office for the construction of platforms was located, and the platforms were being built by collapsing the Yatsuyama and Gotenyama mountains beyond the office. The cliffs were painted by Hiroshige as a different kind of famous place of interest in "Shinagawa Gotenyama," one of the 28 views in Meisho Edo Hyakkei (One hundred Famous Views of Edo).

Let's take a closer look at the actual painting by Hiroshige.

First of all, the rainbow in the sky is a rainbow, although it has lost its color. It is probably an afternoon after the rain.

The rainbow is more than just a rainbow; it is a "Daihachi-guruma" an invention of Ushimachi. It is interesting to note that the design of the wheels of the Daihachi-guruma cart is the same as the wheels of the festival floats still used in many places in Japan.

Many ships are floating on the sea, and together they depict a dais. The reason why the number is somehow obscured by the wheels is probably to avoid being blamed by the shogunate since it is a military facility.

To the left of the horizon, the Boso Peninsula is slightly visible, and a few piles for shore protection are also visible at the edge of the surf. Two dogs are depicted on the beach, and one of them is holding in its mouth a pair of sandals discarded by travelers on the Tokaido. The discarded watermelon peels together give a real sense of summer life.

Hiroshige seemed to love this Takanawa neighborhood and left quite a few works. Please enjoy some of them.

First of all, this painting shows a view of the sea through a large wooden door in Takanawa. The large carriage is also depicted, and the moon, a famous landmark, is also clearly depicted. These large wooden gates were built on the Tokaido Highway in 1710 as a gateway between the inner and outer districts of the Tokaido Highway, and also served as a place to sell tickets to the highest bidder.

In this "Autumn Scene," a beautiful woman watches the sea and the moon from her ryotei (Japanese-style restaurant). You can catch a glimpse of those days with the traffic on the Tokaido and the bustle of reed-bedecked restaurants built on the edge of the waves.

This "Evening View of Takanawa" is delightful because it seems to depict a moment in time, with a large depiction of a large ship at sea from in front of the Ookido, people traveling in a large cart and ox cart, horses and palanquins, and an innkeeper touting her wares.

At first, this Ookido had a wooden door that opened and closed at dawn and dusk, but later the door was removed and only the stone walls on either side remained. The starting point for the survey conducted by Ino Tadataka to map Japan was also at this Takanawa Ookido.

Takanawa no Meigetsu" roughly depicts the earthen mound and high tag at the Okido, the arched shoreline, and the reed screen store for viewing the famous moon. It is interesting to note that the geese that accompany the famous moon are also depicted in a large and realistic manner.

The "Wild Geese on the Moon," which made Hiroshige's name known throughout Japan, was also used as the design for a postage stamp in 1949. It is the type of the three birds on the right.

On the right, Hiroshige I depicts an earthwork at Okido and a procession of feudal lords, while the second generation on the left depicts a bull with a dynamic pattern and a ship on the sea with not only Japanese ships but also foreign flags waving. If you look closely, you can see that the people on the ship in the foreground are also wearing mountain-tall hats, giving the painting a very advanced feel.

In his picture book "Edo Souvenirs," Hiroshige also included this view of Takanawa, emphasizing that it is a magnificent sight. Hiroshige must have liked this view very much.

Finally, please take a look at Hiroshige's rival, Hokusai, who also painted Takanawa. This work is an attempt at Western-style expression with a new copperplate print style touch. It dynamically depicts the earthen mounds of the Ookido, the arched sea, the Tokaido, and Mt.Fuji.

I actually went to this location.

The area that used to be the sea is now under redevelopment around the new Takanawa Gateway station, and only the construction site is visible.

There is a wall in front of me, so I climbed up to the earthen mound of Takanawa Okido, which still remains and took this photo from there.

This is an animation looking toward Shinagawa from what used to be the sea.

This animation shows a view of Daiichi Keihin from the direction of Mita Station to the direction of Shinagawa.

This video shows a view from where Shiba-kuruma-cho stood at the time, looking out from Tamachi toward the sea.

This video shows a view from Shinagawa looking out toward the ocean from where we stood in what was then Shiba-kuruma-cho. Both of them look like incomprehensible construction sites.

When you stand at the Sengakuji intersection, you can see the other side somewhat clearly. However, the ocean is a long way from here.

The construction site is inset in Hiroshige's painting.

This redevelopment project covers almost the entire seaward side of the area then known as Takanawa. Instead of a lunar landmark, it is now a construction site landmark. I wonder if such a huge redevelopment project is still necessary in this covid19-devastated country.Why don't they just make a park instead of building a city?

Since we are here, we decided to leave as it was the invention that drove away the ox carts and craftsmen after the spread of the plague at that time, the Daihachi-guruma. What do you think?

Next time, we will take you to the "Cape with a view of the moon" at Shinagawa-juku.

I visited my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scene looks like today.

I visited my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scene looks like today.

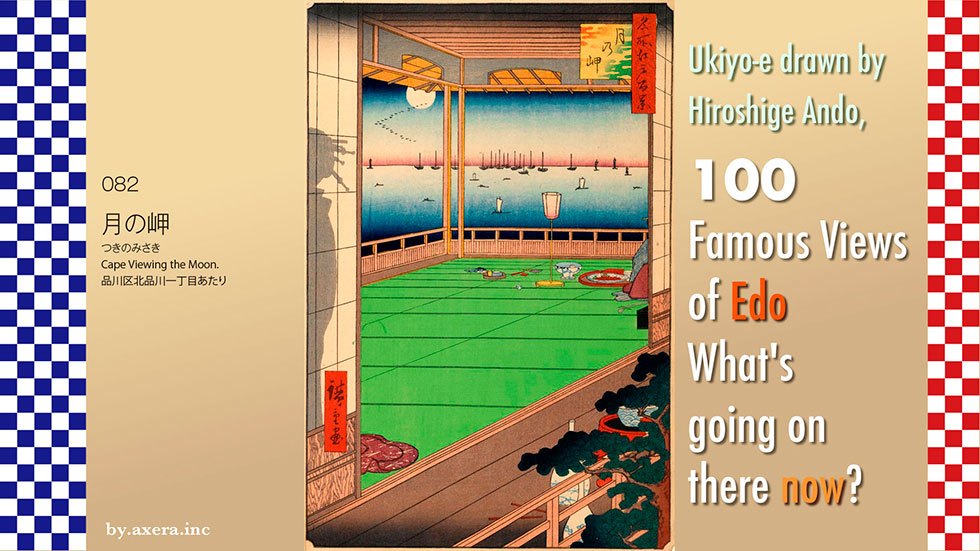

It is said that "Cape Viewing the Moon" in 082 is a view of the sea from around what is now Kita-Shinagawa 1-chome. At the time of Hiroshige, there was nothing to the immediate east of this area but the ocean.

Generally, the name "Cape Viewing the Moon" referred to the Takanawa area on the Mita plateau. This is the area from Mita 3-chome up Hijiri-zaka to the intersection of Isarago, where Mita-dai Park is located today. Until the Tokaido was built along the coast, the most common route west from Edo was through Gotanda and Chigasaki via Nakahara Kaido. It is said that Tokugawa Ieyasu entered Edo by following this route in reverse.

However, Hiroshige's painting seems to have depicted the Shinagawa area.

In the picture book Edo Souvenir by Hiroshige, a view looking toward today's Shinagawa Station from the Yatsuyama area is introduced as "Cape Viewing the Moon.

However, there are no splendid ryotei restaurants in the Yatsuyama area as Hiroshige depicted. Therefore, there was a famous ryotei called "Dozo Sagami" a little further south, around what is now Kita-Shinagawa 1-chome. It is said that Hiroshige may have used this ryotei as the setting for this painting.

Now, please check the map to see where this "Dozo Sagami" is located and in which direction you are looking. This time, I have used a screen capture from Tokyo History Map. The reason is that you can clearly see the transition of the sea topography. First, please look at the GSI map, and then cover it with the map from the end of the Edo period.

Dozo Sagami was located at the end of the street down from the current Keikyu Kitashinagawa Station toward the sea, on the left side of the street to the right. It is thought that the room facing the sea at that time had a view of the sandy beach below and the sea connected to the Meguro River.

As you can see from this map, the sandy beach brought by the Meguro River spread out in the North Shinagawa, and the vast sandy beach brought by the Tama River spread out in the South Shinagawa. The famous rakugo story "Shinagawa Shinju (double suicide)" was set on this vast sandy beach with a prostitute at Shinagawa-juku. The story was made funny because Kinzo, who could not swim, did not die when he was pushed off the pier by Osome, a prostitute, on this shallow sandy beach.

Now let's actually take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

First, outside the window is the sea with large ships anchored far out to sea. The moon is floating in the sky, and geese are flying next to it.

Inside the room, there is a Bonbori (paper lantern), a cup washer, a cup, a tray, a fan, and what looks like red fish sashimi. Next to the tray, the hem of a geisha and the pole of a shamisen (a three-stringed Japanese instrument) peek out. Was she playing with them until now?

On the left, a prostitutes' figure, made up of the shade of an Andon (paper lantern), is reflected in a shoji door. The fact that she has five hairpins in her hair suggests that she is a very high-class prostitute. Who is in the direction the prostitute is facing? It is an interesting pattern that stirs the imagination.

Such a thought-provoking pattern is rare in this series, and the only other paintings in this series that depict scenery in that direction are View 39, "Azumabashi Bridge Kinryuzan Distant View," and View 101, "Asakusa Tanbo Torinomachi Pilgrimage," but View 82 is the only one that depicts scenery that is not in that direction.

Since Hiroshige titled this painting "Cape Viewing the Moon," it is thought to be a scene from just after the annual Nijurokuya-no-Yoru (Twenty-six Night Waiting) banquet held in July.

The twenty-sixth night of waiting is also depicted by Hiroshige in his picture book "Edo Souvenirs" with detailed explanations.

In the Edo period (1603-1867), people waited for the moon to rise on the 26th night of the first and seventh months of the lunar calendar and worshipped it, which was called "26-night waiting. It was said that the three deities Mida, Kannon, and Seishi would appear in the moonlight, and especially in July, the area from Takanawa to Shinagawa, which was said to be one of the best places to see the moon, was very crowded.

Hiroshige left various pictures of this scene.

Many people crowded along the road from Takanawa to Shinagawa, enjoying sake, food, songs and dances, rakugo (comic monologue), lanterns, and street lectures while they waited for the moon to rise.

I actually went to this location. There is now an apartment building with a convenience store where the Dozo Sagami used to be, so I moved a little to the north and looked for a view out toward the ocean, and took this shot.

From this location, swing the camera toward Kawasaki on the old Tokaido. About 30 meters from here, on the left, is Dozo Sagami.

The official name of the inn, Sagamiya, was a storehouse with a sea cucumber fence on the exterior, and was commonly called "Dozo Sagami". Sagamiya was one of the largest brothels in Shinagawa, and was known as the place where Shinsaku Takasugi, Hirobumi Ito, and other patriots at the end of the Edo period held secret ceremonies. The building seems to have survived until the early Showa period.

I swung the camera in the opposite direction toward Shinagawa Station. This is now the Keikyu railroad crossing.

I tried to fit the present image into Hiroshige's painting.

In fact, I took the picture from a slightly elevated position near where the storehouse Sagami used to be, and inserted only the window. Of course, you cannot see the sea at all, only buildings.

A few years after Hiroshige painted this picture, under the name of the Meiji Restoration, the country was being industrialized, the beautiful beaches were being reclaimed, and the sea, which had been a treasure house of fish, was being transformed into a smelly, sludgy sea. The sea, once a treasure trove of fish, has been transformed into a smelly sludge. The time when we are allowed to enjoy the elegance of waiting for the moon to rise while gazing at the beautiful sea will probably never come again.

I wish I could see the three deities appearing in the moonlight.

I visited my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scene looks like today.

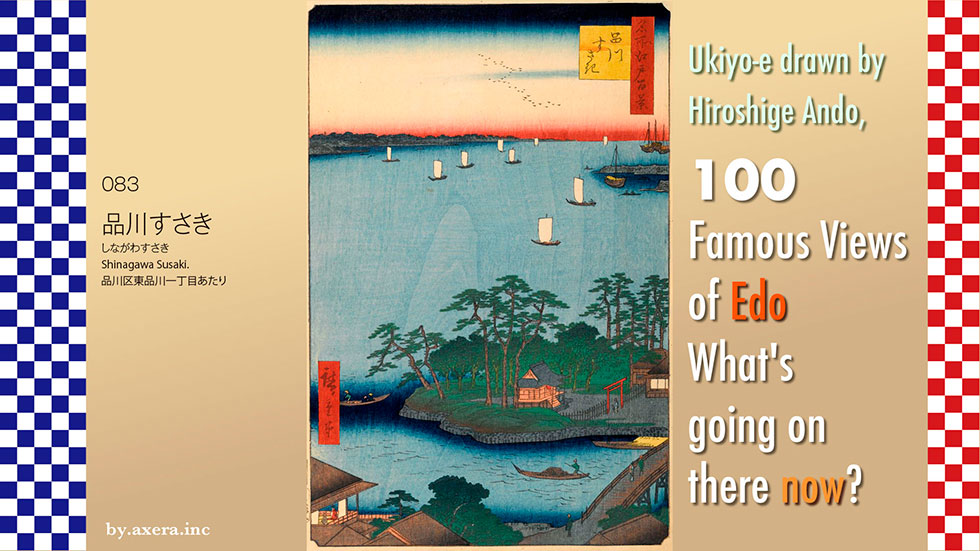

The "Shinagawa Susaki" of 083 is a view of Edo Bay over the Suzaki Benten Shrine in Shinagawa.

Now, please check the map to see where Hiroshige viewed this painting from. It is the sea side of the Old Tokaido, about 1 km south of the present Shinagawa Station. The red gradation represents Hiroshige's viewpoint.

This is superimposed on a pictorial map of the time. The place marked "Benten" at the northernmost end of the sandbar created by the Meguro River is the Suzaki Benten Shrine, which is now Kagata Shrine.

Let us return the map to the present and cover it with another pictorial map. The black areas are the townspeople's areas, the red areas are temples and shrines, and the white areas are samurai residences. You can see that Edo Bay extended immediately to the southeast at that time.

Let us return once more to the modern map, and then cover it with a map of the early Meiji period. The fishermen's town extends along the Meguro River, and the Kagata Shinden is depicted on the west side of the Kagata Shrine. However, this is not a new rice field, but a gun emplacement, or "daiba," built by the shogunate in preparation for the coming of the black ships. At that time, it was called Gotenyama Shita Daiba, and is now the Shinagawa Ward Daiba Elementary School. A little to the west, you can also see the first and fourth daiba. You can also see the vast mudflats on the sea.

Let us actually take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

The geese flying ahead in the distance are seen in the direction of Fukagawa and Gyotoku. On the right side of the Benzaisen floating in Edo Bay, two platforms can be seen. They are the first and fourth batteries.

The one in the middle is the Susaki Benten shrine.

In front of it is the Meguro River, and this Benzaiten was located right at its mouth. The shrine is surrounded by a slightly high stone wall, and pine trees are planted to protect it from the waves. The Benzaiten can be reached by crossing the Torimi Bridge, after which there is a vast shallow beach, which is famous for ebb and flow fishing from before summer.

On the far left, what looks like a ryotei restaurant peeks out, but the Tokaido side is slightly elevated and can be seen for quite a distance, so we were able to enjoy the view while enjoying the play.

Hiroshige II left a painting of a scene of Shiohigari (ebb and flow) fishing in this area. This shows that flounder, clams, etc. were caught in the vast shallow sea.

Hiroshige I painted Suzaki Benten Shrine from a different angle. Beyond the reed screen stalls, Edo citizens enjoying ebb tide fishing are depicted in a small size.

On the left, the shallow sea and nori cracks are depicted outside the window of a geiko eating roasted nori.

On the right, beyond the Edo citizens playing on the beach, the Suzaki Benten shrine is surrounded by a stone wall.

In his picture book Edo Souvenir, Hiroshige depicted the Susaki Benten Shrine in the exact same composition. In the accompanying commentary, he praises the view, which shows that Hiroshige was fond of this area.

I actually visited this place. The Susaki Benten Shrine, now Kagata Shrine, is lined with houses around and on the approach to the shrine, and there is almost no trace of those days.

The place that used to be the Meguro River in the Edo period is now Yatsuyama-dori Avenue with its winding shape, and I took a video of it.

This is the former Susaki Benten Shrine, now Kagata Shrine. It was originally built in 1626 by Priest Takuan, who had invited Benzaiten to a sandbar on the Meguro River.

With the separation of Shintoism and Buddhism in the Meiji era (1868-1912), the deity was changed and the shrine became "Kagata Shrine. It is said to have originated from the "Kagata Clan," the feudal lords of Shinagawa-juku during the Edo period (1603-1868).

There is a small park on the west side of the shrine, along what was then the Meguro River, where a whale was buried in 1798 after it strayed into the waters off Shinagawa. At the time, the whole city of Edo was in an uproar, and onlookers rushed to the site to catch a glimpse of the whale. It is recorded that Ienari Tokugawa, the 11th shogun of the Edo Shogunate, had the whale towed to the present Hamarikyu Gardens to witness the event.

I tried to fit the current photo into Hiroshige's painting. It is a very lonely picture.

Following Views 81 and 82, Hiroshige painted scenes of this area. This is nothing but Hiroshige's great love for the scenery of Takanawa and Shinagawa.

There is one further oddity. This painting was issued in April of the 3rd year of Ansei.

In fact, in the first year of Ansei, the construction of a daiba had started right after this Suzsaki Benten-sha. This platform, called Gotenyama Shita Daiba, was one of 11 planned to counter the black ships and was completed in December of the first year of Ansei. Therefore, Hiroshige intentionally completed this painting without depicting that daiba.

For Hiroshige, it may be that he could not allow a gun emplacement for war to be built in his favorite view of Takanawa and Shinagawa, and he wanted to leave this beautiful view without the gun emplacement forever.

Today, only the third and sixth platforms are still standing in Odaiba. Finally, please take a look at the view from Odaiba looking toward Shinagawa.

I visited the actual location of my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see how the scene looks today.

I visited the actual location of my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see how the scene looks today.

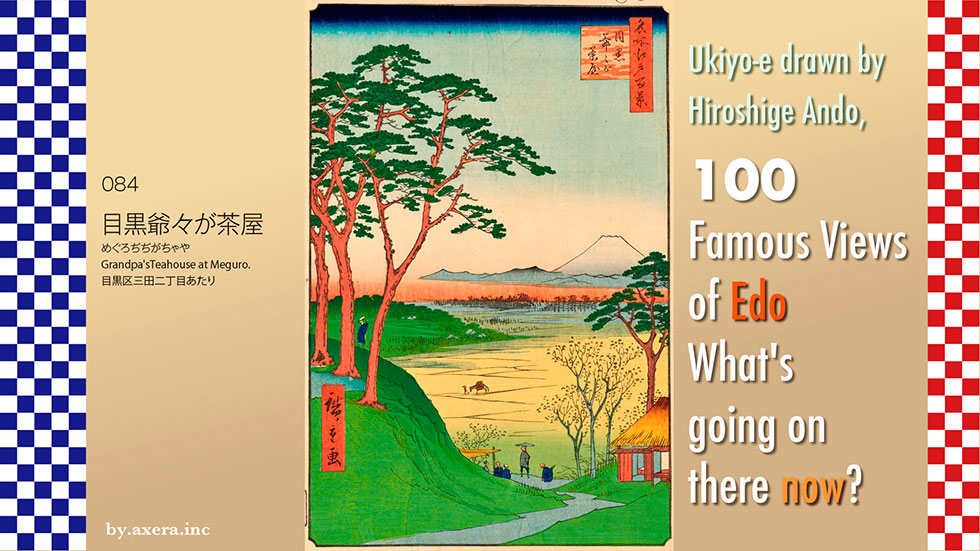

The "Meguro Grandfather's Tea House" in 084 is a view of Mt. Fuji from the top of a steep hill slightly downhill from Meguro Mita-dori.

In fact, please check the location on the map now, just about 1 km south of JR Ebisu station. The red gradation represents Hiroshige's viewpoint.

Let's cover this with a map of the time. The light blue line at the bottom is the Meguro River, and the light blue line at the top is the Mita Waterworks.

Now, here is a map that shows the difference in elevation of the land, although it is a little wide. I added a red gradation to Hiroshige's viewpoint. You can see that river terraces are formed along the Meguro River.

If you zoom in a little more, you can see that the Meguro area is diagonally "elevated" between the Meguro River and the Shibuya River on a map with extreme height differences.

In fact, the south side of the Meguro River here is a cliff, and it was an excellent location from which to view the southwestern direction from high ground. The Mita water supply runs along the cliffs, and the steep cliffs were all scenic spots with good views.

Hiroshige left three views of Mt.Fuji.

Here is an Applemap street view from the sky around Yebisu Garden Place. I will also include the red gradient that is Hiroshige's viewpoint.

The white tent that looms beyond Hiroshige's viewpoint is the Meguro Incineration Plant, which is currently under construction.

The straight road running vertically is Shinchaya-zaka, where the Mita water supply ran from right to left at that time.

Yebisu Beer, which was brewed at the site of what is now Yebisu Garden Place, relied on the water rights of the Mita Irrigation Canal. However, until the very end, there was a dispute with neighboring farmers over water rights.

The building with the long, narrow green roof on the right is a huge pool where the Naval Technical Research Institute used to study the condition of waves on warships and other vessels during the war. This area is now under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Defense.

The Mita Irrigation System continued to flow for more than 300 years until it was discontinued in 1974. The water was diverted from the Tamagawa Waterworks at Kitazawa, south of Sasazuka Station on the Keio Line, and was supplied to the Shirokane area via Oyama, Uehara, Aobadai, and Mita.

In the past, when Shinchayazaka was built, the waterway for the Mita water supply crossed over the hill and was crossed by a tunnel called "Chayazaka Tunnel," but this was removed around 2001 for road widening.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting. Again, please take a look at the high-resolution first print.

The first thing that appears is a pine tree planted on a hill, with Mt. Fuji, and to the left, Mt. Daisen. Under the red misty clouds, what appears to be a pine forest is depicted, which is probably in the Komazawa area.

On the left in the middle, the roof in green is Yutenji Temple, and in the foreground, a horse with a load on its back is walking leisurely along a yellow-colored rice field path. The Meguro River in the foreground is hidden from view. The teahouse on the right, where several Edo citizens are standing, who may have come to see Mt. Fuji, is "Meguro Grandfather's Tea House.

Hiroshige depicted this place in almost the same composition in his picture book Edo Souvenir. According to the commentary, the old couple entertained the shogun when he came for falconry, and the old man and his wife became the teahouse.

Falconry is a type of hunting in which tame hawks are released into the mountains and fields, rather than hunting hawks, for both military training and recreation. Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of the Edo shogunate, was famous for his fondness for falconry, and it seems that he considered it more than a mere falconry hobby, but a definite way of regimen and a way of life for warriors.

Ieyasu had an entourage of falconry technicians, called "falconry gumi," who were paid well as warriors. Thus, during the Edo period, successive Tokugawa shoguns favored falconry.

Two falconers are also depicted next to Mt. Fuji in Katsushika Hokusai's Fugaku Sanjurokei (Thirty-six views of Mt. Fuji) in Shimomeguro.

The third shogun, Iemitsu, in particular, is recorded to have conducted hundreds of falconry trips during his tenure as shogun. However, the 5th Shogun Tsunayoshi abolished falconry with his "decree of mercy for all living creatures," and it was not until the Kyoho period under the 8th Shogun, Yoshimune, that falconry was revived.

There was a teahouse on the way uphill from Dendobashi Bridge on the Meguro River to the present Yebisu Garden Place area. The Shogun often stopped by this teahouse on his way home from falconry to rest. The Shogun liked the simple personality of the teahouse owner, a peasant named Hikoshiro, and called him "Grandpa, Grandpa," which is how the teahouse came to be called "Grandfather's Tea House. Since then, every time the shogun stopped by here, he gave Hikoshiro a piece of silver.

It is said that the shogun at this time may have been Iemitsu or Yoshimune.

Chaya-zaka has always been a very lonely place, though it has always had a beautiful spring and trees, and during the chaos of the Meiji Restoration, the teahouse was often robbed. The teahouse was often robbed during the turmoil of the Meiji Restoration, so "Grandfather's Tea House" was finally moved to the village of Sakashita.

In the Shimamura family, a descendant of the teahouse, there is a document recording that Yoshimune visited the teahouse on April 13, 1738, during a falconry trip and exchanged words with the owner.

There is also a document recording that the Shimamura family served 150 skewers of dumplings and 100 skewers of tofu-dengaku when Ieharu, the 10th Shogun, visited the family. It is said that these anecdotes about the friendly Shogun and "Grandfather's teahouse" led to the birth of the famous rakugo story "Meguro no Sanma" (The saury of Meguro). The story goes that "saury is only available in Meguro.

I actually went to this place. I gradually descended the teahouse slope that still remains. Obviously, you cannot see the other side at all. Perhaps, if I climbed up to a tall building in this area, I could see Mt. Fuji.

I tried to fit the current picture into Hiroshige's painting. Fuji and Yutenji, not to mention the fact that you cannot see the other side at all.

There are about 17 places in present-day Tokyo called Fujimizaka, where, during the Edo period, one could see Mt. Fuji. Most of these slopes are located on higher ground, and the one in Nishinippori 3-chome was the last Fujimizaka in Tokyo where pedestrians could actually see Mt. Fuji. However, it has recently been overshadowed by condominiums, making it impossible to see Mt. Fuji.

On the contrary, Mt. Fuji was a common sight from many places in the town of Edo. Now, however, it is not visible except to residents of high-rise condominiums or houses on high ground open to the southwest. Fuji could be seen from anywhere on the north side of the Meguro River, from Mita to Aobadai, which used to be a famous spot with few houses in the Edo suburbs. Today, it has been completely developed and there is not a shadow of Fuji to be seen. Fuji" from Tokyo has become a privilege only for the rich?

Lastly, I would like to insert a picture of beautiful Mt. Fuji as seen from Tachikawa, west of Tokyo, on the morning of January 3, 2023.

I visited the place where my favorite artist Hiroshige Ando painted "Meisho Edo hyakkei" (One hundred Famous Views of Edo) to see what the scene looks like nowadays.

I visited the place where my favorite artist Hiroshige Ando painted "Meisho Edo hyakkei" (One hundred Famous Views of Edo) to see what the scene looks like nowadays.

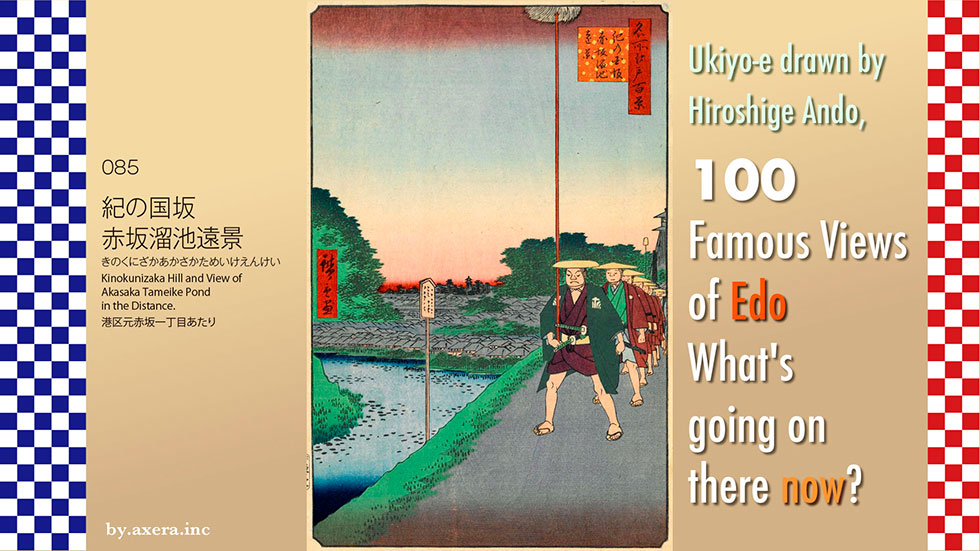

The "Kinokunizaka Hill and View of Akasaka Tameike Pond in the Distance" (085) is a view of the Tameike from the downhill east of the State Guest House Akasaka Palace. Actually, the pond on the left is not Tameike but Benkei-bori. The publisher, Uoei, wanted to include the word "Tameike" in the title because pictures of Tameike were very popular at that time.

Please check its location with Applemap first.

From Yotsuya Station, there is a descent along the moat that goes around Akasaka Imperial Palace. The blue line indicates the location of what is now named Kinokunisaka. It descends from the left to the lower right.

This map is enlarged.

The large green area on the left is the State Guest House and the Akasaka Imperial Palace, the residence of the Imperial Family, among others. This area was the central residence of the Kishu Tokugawa family of 555,000 goku during the Edo period. The Hotel New Otani Tokyo on the right was the residence of the Ii family of the Hikone domain.

The moat between the two was called Benkei-bori, after Benkei Ozaemon, who was the contractor for the construction of the ditch. Nowadays, many people enjoy bass fishing here in rowboats. The moat and greenery alone make it hard to believe that you are in Tokyo.

The map of the time is shown with Hiroshige's viewpoint in red gradient.

The gray areas are townhouses and the white areas are daimyo's residences. Except for large roads such as Aoyama-dori and Sotobori-dori, the narrow roads are almost the same as now, as you can see.

Here is a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

The upper half is almost sky, and the green on the left is the forest of Sanno-Hie Jinja Shrine. There is a Tameike pond below it, but it is not even light blue, as if he forgot to add color to it. It is a distant view in name only.

The fire watchtower on the right is because there was a residence of a fireman here. This is where the Tokyu Agency building stands today. The greenery in the middle is the forest leading from the Asano family of the Hiroshima clan to the Hikawa Shrine. It is around the area from the present TBS Broadcasting Center to the U.S. Embassy dormitory.

The town with its folded roofs runs from Moto-Akasaka to Toranomon area. In the foreground, to the left is Benkei-bori, and on the right, a procession of feudal lords led by foot soldiers with hair spears is now descending Kinokunisaka. This procession is on its way back to the central residence of the Kishu Tokugawa family, and although there are actually two lines, the one on the right is obscured.

Here is where something strange turns out to be true. The present-day Kinokunisaka slope goes all the way down from the direction of Yotsuya with Benkei moat on the left, but in this picture, the procession of feudal lords is coming down from the direction of Akasaka toward Yotsuya.

To elucidate its strangeness, I actually went to this location. This is a photo taken from the sidewalk with my back toward Yotsuya. Benkei moat is on the left, Kinokunisaka slope is on the right, and the elevated Shinjuku line of the Metropolitan Expressway turns sharply left along the moat toward the intersection of Akasaka-mitsuke. You can see that the road goes all the way down.

This is a Google Earth capture of the view from the roadway. If you look closely, you can see that the roadway on either side of the towering Alsoc building in the center of the front elevation is slightly elevated.

A closer photo would make it easier to understand.

This is a picture of the lowest point. From here, you can see that it is indeed descending this way.

Please look at the map again here.

Kinokunisaka descends from the Yotsuya direction to the bottom of this blue line, but from there it is almost flat.

As can be seen from the old map, Tamagawa-josui, which was formed by a gutter at that time, ran along the south side of Benkei-bori and supplied drinking water to the Toranomon area. This Tamagawa-josui flowed out from the residence of the Kishu Tokugawa family and became a crank.

It seems that there was a waterway under this crank where rainwater and pond water from the Kishu-Tokugawa family's property flowed into the Benkei moat. Because it was a waterway, it was naturally at its lowest point, and from today's Moto-Akasaka area, it went down to an uphill slope known as Kinokunizaka.

The location of the fire watchtower on the right side of the painting is also indicated by the blue dotted line. You can see the words "Joubikeshi" (fire extinguisher).

In searching for documents, we found a photograph of this area taken by Felice Beato, a photographer who came to Japan at the end of the Edo period. It was taken around 1868, about 10 years after Hiroshige painted this picture.

This is a photo looking down toward Akasaka-mitsuke from around what is now Nagatacho station. Along the Benkei moat, a bamboo barrage was installed, under which the Tamagawa-josui (water supply) flows. The blue frame is Benkei Bridge, which had not yet been built at that time. Beyond the bridge, the red circle indicates where the bamboo barrage has been cut off. This is where the Tamagawa-josui intersected with the Kishu-Tokugawa family's waterway. After all, this area seems to have been the lowest land.

I inserted a photo taken from the current sidewalk into Hiroshige's painting. It is difficult to see the relationship between the slopes in this picture, so I replaced it with a picture taken from a lower location a little further ahead.

This would make a nice angle for the Kishu-Tokugawa family's daimyo procession coming down the hill. The black building in front is the Sumitomo Chemical building facing Aoyama-dori, and to the far right was the fire watchtower of the fire extinguishers. Nowadays, you can't see the fire watchtower or even beyond it, though.

The name "Akasaka" is derived from the fact that today's former Akasaka is a slope that climbs up to Mount Akane near the Akasaka Imperial Palace where Akane grass grows. Therefore, the title of Hiroshige's painting, "Kinokunizaka Hill and View of Akasaka Tameike Pond in the Distance," may be correctly understood as a distant view of a procession of feudal lords coming down Akasaka and the Tameike, as seen from Kinokunisaka.

I visited the location of my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scene looks like today.

I visited the location of my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scene looks like today.

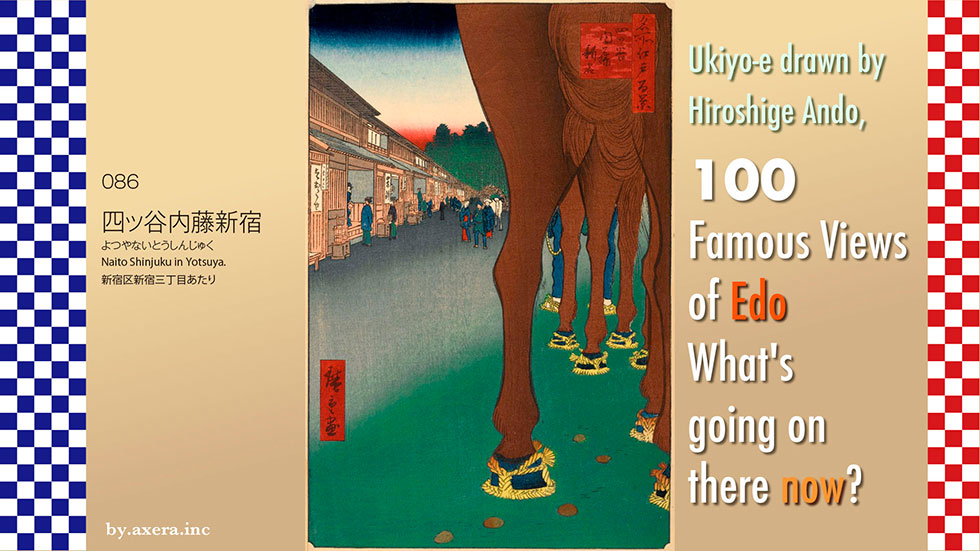

Naito Shinjuku in Yotsuya" (086) depicts a view looking toward Yotsuya from around Shinjuku 3-chome on Shinjuku-dori.

First, please take a look at Applemap to see where we are.

Roughly speaking, it is around the east side of the current Isetan Shinjuku.

Using a slightly more enlarged map, I will add a red gradient to the location where Hiroshige's viewpoint would have been. It is said that this is the view looking toward Shinjuku 2-chome from the current Shinjuku-dori street.

This map is covered by an old map of the time.

In the center of the map, you can see the word "Oiwake," which was called "Ome-kaido" because this was the dividing road between the Ome-kaido road going west and the Koshu-kaido road going southwest.

In reality, the Koshu-kaido road was heading south from this old map, so I have corrected it by cutting it out a little to reflect the actual situation.

This area was a post town located between Nihonbashi and Takaido on the Koshu-kaido, and was one of the four post towns in Edo along with Senju, Itabashi, and Shinagawa. In 1590, Kiyonari Naito, who was the general magistrate of the Kanto region, received a large tract of land from Ieyasu Tokugawa, who told him, "I will give you as much land as you can ride your horse on," and settled there. In 1698, an inn was established on the north side of the premises of the Mikawa Naito family, which became the lord of the Takato domain in Shinshu, and was called "Naito Shinjuku" in contrast to Takaidojuku.

Please see a more extensive map to see beyond the Ome Kaido and Koshu Kaido, which separate from Naito Shinjuku to the north and south. The red road is Ome Kaido and the blue road is Koshu Kaido, and I have drawn lines along both old roads on the present map.

Ome Kaido was a road used to transport lime from Nariki and Osogi, beyond Ome, by horseback at the beginning of the Edo period when Edo Castle was being rebuilt. For this reason, the road was called Nariki-michi until before the Meiji era (1868-1912). Edo Castle was a pure white castle like today's Himeji Castle, and the original building material, plaster, was transported from this Ome Kaido to Edo via Naito Shinjuku.

Later, the Ome Kaido became an important distribution route for booming Ome cotton, sweet potatoes from Kodaira, charcoal from Okutama, and vegetables from the Itsukaichi Kaido.

In fact, the Ome Kaido was also called the Koshu Ura Kaido because it passed through the Daibosatsu Pass and rejoined the Koshu Kaido east of Kofu.

It is said that the Koshu Kaido was built to serve as an evacuation route for the shogun to Kofu in the event of the fall of Edo Castle when Tokugawa Ieyasu entered Edo. As a result of the battle of Sekigahara, Kai Province came under the direct control of the Tokugawa clan, and the areas along the Koshu Kaido were ruled by Tokugawa fiefs or Tokugawa lords, and the Naito family was one of them.

Here is a map captured from the Tokyo History Map website. You can see that at the end of Hiroshige's viewpoint, indicated by the red gradient, there are four groups of guns, the Iga, Negoro, Koga, and Aoki groups, called the Twenty-Five Horsemen Group, which were placed in position. These were prepared to escort the shogun to Kofu Castle in the event of an emergency. Today, the Hyakunin-cho district in Okubo is named after the Iga clan that moved into the area.

Taisoji Temple, a Pure Land Buddhism temple, was built in 1668 with a donation of land from Shigeyori, the eldest son of Masakatsu Naito, lord of the Takato domain in Shinshu, and prospered as the family temple of the Naito family. In addition to the six "Edo Roku Jizo" statues built to mark the entrances and exits of the city of Edo, there is also a statue of Enma, who was worshipped by the people of Edo. In those days, the temple was also the center of the bustle of the inn, with a nakamise (a shopping street) built along the approach and in the precincts of the temple.

Please see the picture book "Edo Souvenirs" by Hiroshige. Only three clans, the Shinano Takato, Takashima, and Iida clans, used this Koshu Kaido for their pilgrimage, while the other clans used the Nakasendo. Even so, Naito Shinjuku developed as a logistics center as grapes from the Koshu area, silk from Hachioji, gunpowder from Chichibu, and other goods were brought to the area.

Another aspect of Naito Shinjuku's history is that of an "entertainment district.

Although the area outside Yotsuya Okido was outside of Edo, in 1697, five townspeople, including Kihei Takamatsu, a master of Asakusa-Abekawa-cho, petitioned the shogunate to establish a new lodging house by paying 5,600 ryo in gold to the shogunate as a freight payment. Since Takaido, the first inn on the Koshu Kaido, was about 4 ri (about 16 km) away, the ostensible reason was to secure convenient lodging, but in reality, the purpose was to develop a new downtown area.

In this newly developed lodging town, more than 50 unauthorized brothels, ostensibly inns, but actually prostitution districts, lined the streets, and the area was very crowded with playgoers who came from Edo. However, due to excessive public morals and complaints from the proprietors of Yoshiwara (the largest entertainment district in Edo), Naito Shinjuku was forced to close down after only a little over 20 years.

In April 1772, Naito Shinjuku reopened after more than 50 years. The ostensible reason for the reopening was to increase the distribution of goods to Edo. In reality, however, it was an attempt on the part of the shogunate to use the revenues from the downtown area to secure finances. With the reopening of the inns, Naito Shinjuku became bustling again, and by 1808 it had grown into a large entertainment district with 50 inns and 80 pull-out teahouses. At this time, up to 150 prostitutes, called "meimori onna," were officially allowed in the area, but it is said that the actual number was more than twice as many.

Let's take a closer look at the actual Hiroshige painting.

The brown horse's hips and tail occupy 1/3 of the picture. This is Hiroshige's signature composition. Beyond the two horses, we can also see the legs of the stable boys. On the left is an inn, and you can almost hear the conversation between the owner and the traveler who recommends staying there. The thickly green area in the back is the forest of either Taisoji Temple or the Naito family's water guard station, and a white horse carrying a load of straw-covered straw on its back is also depicted below it.

At the bottom of the painting, several pieces of horse manure on the road are depicted. The Koshu Kaido played a major role as an industrial road, and this tells us that horses and horse manure were an everyday scene for the townspeople of that time. If you look closely, you can see that the horses' hooves are covered with sandals, just like humans.

Horseshoes did not come into use in Japan until the Meiji period (1868-1912). During the Edo period, native horses had relatively strong hooves, and horses used to carry loads were made to wear sandals called umagutsu (horse shoes) to prevent their hooves from being damaged.

A horse's sandals lasted only about 8 km, and it was necessary to have the horses change their sandals each time, so spare sandals were a must-have for the horsemans.

It can be said that this painting by Hiroshige contains all the motifs of Naito Shinjuku at that time.

The Shinjuku Museum of History, located in Yotsuya Sanei-cho, displays a reconstructed model of Naito Shinjuku as it was then. The road joining the street from the right in the foreground is Koshu Kaido, and the wide road running vertically to the back is today's Shinjuku Dori, beyond which is Yotsuya. The lower left is the current Isetan area, and across from it is Oiwake Dango.

In the Edo period, a drone flying over Hiroshige's viewpoint would have created this atmosphere.

I actually went to this location. First of all, the Oiwake Dango, which was on the right side of Hiroshige's viewpoint, is still in existence, although it is inside a building.

Now, standing in Hiroshige's point of view, the view looks like this. To the right are Marui and a movie theater. Underground here is the Marunouchi Subway Line and the Fukutoshin Subway Line, which crosses the street. A little further ahead, Meiji Dori crosses on either side, and the Toei Subway Shinjuku Line intersects the Marunouchi Line underground.

When Hiroshige painted this picture, the population of Japan was about 30 million, of which about 21 million were farmers. Horses, including farm horses and stagecoach horses, numbered about 600,000, and were used as family members, workers, and means of transportation.

I tried to fit the modern landscape into Hiroshige's painting. Since I wanted to show the horse in the foreground, I put a "car" in the foreground, which is positioned like a horse in modern times.

Naito Shinjuku, once a transportation hub at the intersection of Ome Kaido and Koshu Kaido, has now become a railroad transportation hub for JR, private railways, and subways, and has been transformed into Shinjuku Station, which boasts the highest number of passengers in Japan after the "Naito" was removed.

As an entertainment district, Naito Shinjuku changed its name to Kabukicho and became world famous as a nightlife district that never sleeps 24 hours a day. The area that was the actual center of Naito Shinjuku has become even more popular abroad than Kabukicho as a gender-free, free town called Shinjuku Nichome. Hiroshige's paintings depict horses and horse manure in everyday life, but from a different perspective, they are also paintings filled with various thoughts and ideas that lead to today's Shinjuku.

I visited the actual location of my favourite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scene looks like today.

I visited the actual location of my favourite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scene looks like today.

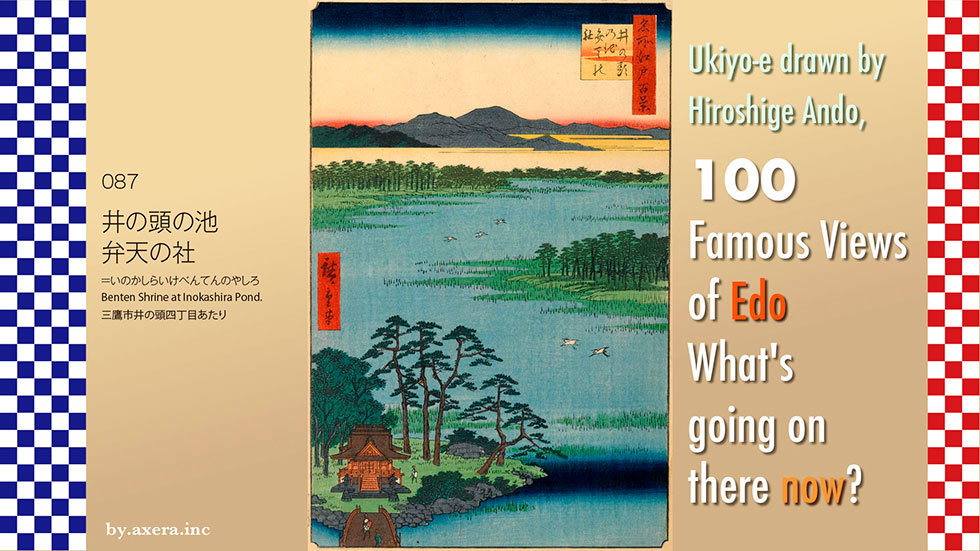

087, 'Benten Shrine at Inokashira Pond', depicts a view of Benten Shrine and the surrounding pond in Inokashira Park, seen from a little higher up.

First, see where we are from Applemap.

Benten Shrine is located in Inokashira Onshi Park, south of Kichijoji Station on the Chuo Line.

See enlarged map. The large park that looks like the letter 'Tsu' in hiragana turned upside down is Inokashira Onshi Park. In the park, there is now a pond that looks like the letter 'Y' turned sideways, which is Inokashira Pond. To the west of the letter 'Y' is a steep cliff, and this area was a rich spring area in Musashino, with about seven springs. The water was supplied mainly to Kanda and Nihonbashi, so it was named Kanda Josui (Kanda Waterworks), and it supplied water to the city of Edo.

The rivers are shown on a wide-area map. At the top is the Zempukuji River flowing out of Zempukuji Pond, and below it is the Kanda Waterworks, which flows out of Inokashira Pond and eventually joins the Zempukuji River, Myoshoji River and Hanazono River to form the Kanda River, which flows into the Sumida River.

When Tokugawa Ieyasu first entered the Edo government, he ordered Okubo Tadayuki to build the Kanda River from this pond to supply water to Edo, where water supply was scarce. It was completed around the time of the third shogun, Iemitsu, who came here on a falconry trip and named the pond 'Inokashira', because it was shaped like a wild boar's head.

Later, in 1654, the Tamagawa Josui water supply was completed, and the water supply to Edo developed dramatically. The area is shown in dark blue on the map.

Please see the GSI map showing the difference in elevation here. This area is just at the eastern end of the Musashino Plateau, where there were abundant springs and several rivers flowing through. Inokashira Pond was one of these abundant springs.

The Senkawa River has its source in Mitaka, the Nogawa River in Kokubunji Koigakubo, and the northern side of the river terrace of the Tama River is the Tama River spring cliff, which is called ’Hake’ by the local people.

Benzaiten is placed in Sanpoji Pond, the source of the Shakuji River, Zempukuji Pond, the source of the Zempukuji River and Inokashira Pond, the source of the Kanda River, all known as the three major springs in Musashino.

Sarasvati, originally a Hindu goddess, was incorporated into Buddhism, then into Shintoism through the Shinto-Buddhist syncretism, and after the Middle Ages she was incorporated into the Seven Deities of Good Fortune.

Since Sarasvati was originally an Indian river goddess, Benzaiten has been enshrined and worshipped at places related to water, such as wells, reservoirs, rivers and springs. The Benzaiten of Inokashira Pond, combined with the scenic beauty of the surrounding area, seems to have made it a popular tourist attraction at the time.

Let us now take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

The first mountain in the far distance is said to be the Nikko mountain range. Below that is the direction of Shakujii and Oizumi, and nearby you are looking in the direction of Kichijoji station.

The light blue area that takes up most of the screen is part of Inokashira Pond, which is now about 42,000 square metres. Even if it was a little larger at the time, it is still a little exaggerated. Five egrets are also depicted, and the island part depicts a pine forest. Rocks have been piled up on the seawall of Benten Shrine, and a bridge is being crossed by people who are going to visit the Shrine.

The hall of Benten Shrine is still red in colour and, according to legend, was built here in the mid-Heian period by Saicho to house a statue of the goddess Benten. The Inokashira Pond depicted by Hiroshige is considered to be an autumn scene, which is a little sad, but today, cherry trees have been planted around the pond, making it a tourist attraction that attracts many people during the cherry blossom viewing season.

Hiroshige also depicted this Benzaiten in his picture book Edo Tosa. In an almost identical composition, the Nikko mountain range is also depicted in the distance.

Separately, a snowy scene of Benten Hall is also depicted. The quiet view of the snow falling shows that it was a tourist attraction even in winter.

Since you are here, please also visit Benten-do, painted by Kawase Hasui. The contrast between the red of the hall, the white snow and the deep blue of the pond is stunning.

Now, I actually went here.

This is the Benten Hall from the front, I went there in 2023, when it was fresh green, and I took this picture.

Here are some photos from a visit in autumn 2021.

If you put it all together in Hiroshige's signature composition, does it look like this?

Standing with my back against the cliff, I looked around the hall from the west.

The bridge is actually a surprisingly thin, short and cozy hall.

This is a view of the autumn foliage from the hall side.

Looking from the back, the pond has a fountain in it, and beyond the Benten Hall, the roof of Daiseiji Temple, which was the temple that managed the Benten Hall during the Edo period, can be seen.

The well is said to have got its name from the water in the pond, which Ieyasu Tokugawa used to make tea when he visited the area. The water is still gushing out from the well. The well is actually dug and pumped up by a pump.

To get closer to Hiroshige's viewpoint, I climbed up the cliff a little, but the trees were in the way and I couldn't see beyond it.

We relied on Applemap street view.

Google Earth may be a better way to see the mountains.

So I tried to fit this painting into Hiroshige's painting. It's a bit of a stretch, but I think it gives the general atmosphere.

In fact, a serious problem is now occurring in this water-rich area. In the Musashino Hills we have seen so far, there are a number of municipalities that use groundwater for their tap water. The well water from these sources is said to be contaminated with a suspected carcinogenic organofluorine compound called PFAS. According to a citizens' group that conducts blood tests on residents, the contamination is spreading mainly in Kokubunji and Tachikawa, and seven cities have stopped mixing water from their wells.

The suspected source of contamination is the US Yokota Air Base, where a British journalist reported that a large amount of foam firefighting agent containing PFAS leaked into the soil between 2010-17, and a survey in 2018 found the highest concentration of PFAS in Tokyo in a well near the base.

The right-hand edge of the image is the US military base at Tachikawa. The view extends from Fussa to the Fuchu area.

The problem is that this contamination is spreading further and further downstream on groundwater, and that there is too little coverage of this. Another problem is that neither the Tokyo Metropolitan Government nor the Government is serious about this issue. It is said that this is due to the consideration for the US military privileges that the US-Japan Joint Commission has.

Even Inokashira Pond, painted by Hiroshige, is now already contaminated with carcinogens, rather than being used for making tea.

I visited the actual location of my favourite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scene looks like today.

I visited the actual location of my favourite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scene looks like today.

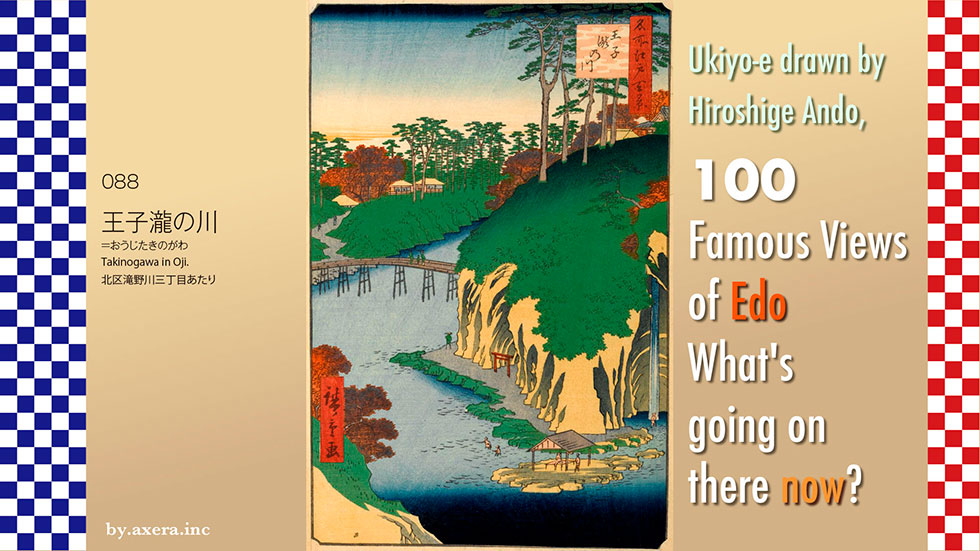

Takinogawa in Oji in 088 depicts a view of the Oji area, downstream from the Shakujii River.

First, please check the Applemap to see where this location is, about 1.5 km west of JR Oji Station.

As you can see from the enlarged map, if you walk upstream from Oji Station along the promenade along the Shakujii River, the third bridge is the Momiji Bridge, and you can still find a rather large temple called Kongoji on its right bank. This is on the west side of that temple. I added a red gradation to Hiroshige's viewpoint.

At that time, however, the Shakujii River flowed in a very meandering direction, roughly in the shape of a dark blue line.

This was covered by a pictorial map of the time, but the road locations and directions are so different that this can only be used as a reference for the name of the facility.

Next, please see the map from the GSI (Geospatial Information Authority of Japan), which shows the difference in elevation.

The Shakujii River is fed mainly by the Sanpoji Pond in Nerima and flows eastwards across the Musashino Plateau into the Sumida River. However, it is called the Otonashi River and meanders past Naka-juku on the old Nakasendo road, and in the Edo period it showed the beauty of its valleys according to the seasons.

The Oji area was also a popular spot just the right distance from Edo at the time, which could be visited overnight, and was a mature tourist destination with natural beauty and recreational areas.

This map is covered by a geological map from the website of the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology.

In the Edo period, the Shakujii River passed the Toshima-dai Plateau of the Musashino Plateau (Musashino terrace deposits) and entered the Hongo-dai Plateau, a deposit with a different geology represented in a slightly darker green colour, around Nakajuku, crossed the Ueno-dai Plateau and dropped down from Asukayama at Oji in one stroke.

Long before that, in the Jomon period, the Shakujii River was the sea to the side of Oji Station, and the Shakujii River tried to cross Hongodai Plateau and Uenodai Plateau. However, it did not actually cross over, and there was a time when it went south for a while, along what is now Senkawa-dori, crossed the Koishikawa, and poured into the Hibiya inlet from around Suidobashi. There was also a time when the river did not cross Asukayama and continued southwards, becoming the Yata River and the Aizome River, passing through Komagome and Yanaka before emptying into Ueno.

It appears that at that time it formed a deep gorge, bent as it is now. However, on the Musashino terrace deposits of peat, the Otonashi Gorge created by the Shakujii River is a special case, and the only other gorge that is known to have formed is the Todoroki Gorge.

Now let's actually take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

The red colour of the maple trees indicates that this is an autumn painting. In particular, the temple on the right, of which only the roof is visible, is the Kongoji Temple, which still exists today and has been nicknamed the 'Autumn Leaves Temple' since that time, attracting many tourists.

The river that meanders through the area is the Shakujii River, which in this area was called the Otonashi River. The road on the left bank ends at Oji, and after crossing a bridge called Matsuhashi Bridge to the right, there were two slopes, one going up to Kongoji Temple and the other going down to Iwaya-benten , which could not be seen behind rocks.

The Iwaya Benten, where the red torii gate is visible, and the Benten Waterfall was located around it. People actually swimming in the waterfalls, resting or in the river are also depicted. In addition to Benten Falls, many other rivers flowed down in the valley around here, which is why this area was also known as the River of Waterfalls.

In Hiroshige's 100 Views of Edo, there are six paintings depicting this Oji neighbourhood, including one that has not yet been introduced. It was certainly a popular tourist destination, but Hiroshige seems to have liked the area very much. See the six painted views in succession.

Hiroshige painted this neighbourhood in addition to the Edo 100. This painting depicts the Iwaya Benten and citizens playing on the Otonashi River in search of cooler weather.

This painting shows Kongoji Temple in autumn leaf colour over the Maruhashi bridge.

The season is spring, and the painting depicts people coming and going on the pine bridge over the Otonashi River and cherry blossoms.

The painting on the left shows Iwaya Benten and the waterfall together over the Matsuhashi bridge, with emphasis on the maple trees.

The painting on the right is similar in composition to the first Hiroshige painting, but by the second Hiroshige.

Finally, if you also look at the Edo Meisho Zue, you can see the actual location of Matsuhashi, Iwaya Benten and the Benten-waterfall.

We actually went to this location. The first thing you notice is that it has been completely revetted with concrete. The meandering river has also been straightened. The Iwaya Benten was located next to the stairs in the front. Behind the front is Kongoji Temple.

The area where the Otonashi River used to meander is now the Kita-ku Otonashi Midori Park.

This is the view from Google Street View from that park. There is a monument to the 'Matsuhashi Benzaiten Cave Site' at the top of the front steps.

This is a view of the Takinogawa Bridge upstream. The concrete revetment is fine or painful.

This is a view of the still extant Kongoji Temple, commonly known as Momiji Temple, from the opposite bank on the Oji side of the river.

I have tried to fit the current photo into Hiroshige's painting. Of course, waterfall rafting and playing in the water are not allowed, and except for this park, we can't even go down to the water's edge. I understand that the shape of the park has to be this way because of the lives of the people who live there. However, the valley, which in the past had the appearance of a beautiful deep valley, is now like a huge sewer with a continuous concrete revetment. Is this also the sad fate of urban rivers?

A little closer to the station than the Kongoji temple in the centre of the photo is the Otonashi Sakura Green Park, also created by correcting the meandering of the river, where you can see outcrops of a geological formation called the Tokyo Formation, which was formed 120,000 to 130,000 years ago, when the area around present-day Tokyo was under the sea floor. If you are interested in this miraculous geological formation created by the Shakujii River, please visit.

I visited the actual location of my favourite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Ando Hiroshige, to see what the scene looks like today.

I visited the actual location of my favourite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Ando Hiroshige, to see what the scene looks like today.

089, 'Moon Pine at Ueno', depicts a rounded pine tree said to have been under the Kiyomizu Kannon Hall in Ueno Park, and the view beyond.

The pine tree was located on the shores of Shinobazuno Pond, west of JR Ueno Station.

See also an enlarged map. Keisei Ueno Station lies underground to the east of Shinobazuno Pond, and the moon pine tree was about ground level to the north of the station. Hiroshige's viewpoint is shown in red gradient.

This is covered by a pictorial map of the time. The actual Shinobazuno Pond was about 1.5 times this size from north to south. On the east side of the pond, the Ueno mountain and Kan-eiji Temple occupy a vast area.

On the west side are the houses of the feudal lords, the largest of which is the residence of the Maeda family of the Kaga clan. Most of these are now occupied by the University of Tokyo.

Hiroshige painted a series of three bird's-eye views of this Shinobazu Pond from the south-west. The island on the left in the painting is Nakajima, where the vermilion-lacquered Benten shrine is located, surrounded by ryotei restaurants. When the island was first built, it was accessed by boat, but eventually a bridge was built and it became a popular spot for Edo residents to view lotus blossoms, cherry blossoms, cooler temperatures, the moon and snow throughout the four seasons.

I will also include Hiroshige's point of view in this painting in a red gradient.

In fact, in view 11 of the Edo 100, Hiroshige depicted this winding pine tree in a small way in his presentation of the view of the Kiyomizudo Hall and Shinobazu Pond in the Kan-eiji precincts. This time, in the 89th view, he published it again with this pine tree as the main theme.

See the full map of Shinobazuno Pond again. This area around Kan-eiji Temple in Ueno was modeled after Kyoto by the monk Tenkai, who was entrusted with the design of the city of Edo. The mountains of Ueno were named Toeizan, as Hieizan in the east, and Shinobazunoike Pond is Lake Biwa to its east. Nakajima is Chikubujima, and the actual Benzaiten of Chikubujima was recommended and named Nakajima Benzaiten.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting. The brown pine tree called 'Tsuki no matsu' (moon pine) largely closes the entire screen. On the other side of the tree are the town houses of Ikenohata, and at the far end, where the three fire watchtowers on the Hongo Plateau can be seen, there was a row of daimyo residences as far as the Nakasendo road at the far end of the area. This is a view unique to Edo, where fires were common. The largest of these residences was the Maeda family of Kaga Hyakumangoku, who organised their own group of firefighters called the 'Kaga Tobi'. Also known as the 'fighting steeplejacks', they had too strong a sense of privilege and often came into conflict with the town firefighters and the regular firefighters.

The name 'Kaga-Tobi' is now one of the brands of delicious sake produced by Fukumitsuya in Kanazawa.

The black spots on Shinobazuno Pond are lotus flowers, which bloomed in white and pink in June, making it the best lotus-viewing sightseeing spot in Edo. The restaurants around Nakajima Benzaiten served lotus rice, which seems to have been particularly popular among Edo citizens.

The 'moon pine' was not specifically depicted in Hiroshige's bird's-eye view of Kan'eiji Temple, and no pine tree that looked like it could be found in the Edo Meisho Zue, drawn in 1872.

In Hiroshige's series of paintings of famous ryotei restaurants, the fire watchtower of a daimyo's house is depicted in the outside view.

The Kawachiro is even depicted with a warehouse on the left. The main residence of Hisaya Iwasaki, the third president of the Mitsubishi Group, would eventually be built in this area.

I did some more research on the 'moon pine', which Hiroshige painted twice. It seems that 'Aioi-Matsu' and 'Kamenoko-Matsu' are the most famous pine trees in the Ueno Mountains, but 'moon pine' does not appear either in the paintings or in the descriptions. The reason for this seems to be related to this mountain in Ueno.

Eleven years after Hiroshige painted this scene in 1857, the Boshin War began in 1868. It was the largest civil war in modern Japanese history, fought between the old shogunate forces and the new government forces led by the Satsuma, Choshu and Tosa clans, which had raised Emperor Meiji to power.

One of these battles, the Ueno War, took place between the old shogunate forces, including the Shogitai, and the new government forces in Edo Ueno. The title of this picture is Honnoji Battle, but this is a picture of the battle at Kan-eiji Temple in Ueno. The soldiers in hakama are the Shogitai and the soldiers in black and red Western-style clothing are the new government forces. The 'moon pine' seems to have been located on the right side of the painting, in front of the black gate, where it is cut off.

This is a map of the locations where the Shogitai war dead were found during the Ueno War. The black dots on the map are the locations. It seems that the 'Moon Pine' was located around the blue circle. The Kan'eiji precincts were burnt to the ground in this war, and were then largely off limits to the public until February 1869. According to a description in the book 'One Hundred Contrasting Views of Edo, Now and Then' published in 1919, the 'Moon Pine' was broken by a storm around the beginning of the Meiji era (1868-1912), and it seems to have withered quietly because it was off-limits to the public. Nevertheless, until around 1919, there were many people in the Ueno area who remembered this pine tree.

According to the 'One Hundred Contrasting Views of Edo, Now and Then', the pine tree was located on the edge of the bank below the Kiyomizu Kannon-do Hall, facing the Shinobazu Pond, and was also known as the Moon Pine, also known as the Wana no Matsu. It is described that its ring of branches looked different depending on where and from what angle it was viewed, and that it looked different from the new moon to the full moon.

The Boshin War then moved through Aizu and the north-east, ending with the Hakodate War in May 1869. As the saying goes, "As long as you win, you're regular army", the coup was renamed the "Meiji Restoration" and history was subsequently rewritten to suit the new government.

I actually went to this place. To my surprise, this "Moon Pine" had been restored. The location is just below the Kiyomizu Kannon-do Hall, so it is a little different from the location at the end of the Edo period, but there was a pine tree there that looked like it did back then. Looking at it from the front, there was also a magnificent introduction plaque saying "Utagawa Hiroshige's Moon Pine". Looking up from below, the pine tree stands out against the vermilion-lacquered Kiyomizu Kannon-do Hall.

The current appearance is framed in Hiroshige's painting. In Hiroshige's painting, the town in the direction of Ikenohata was contained within a ring of pine trees, but now the rebuilt Benten-do can be seen completely inside.

Hieizan in Kyoto, which was the motif for Ueno Mountain, was devastated by Oda Nobunaga. Toeizan Kan-eiji Temple, built in imitation of it, was also burnt to the ground by the new government forces.

The "Moon Pine", a favourite of Hiroshige's, was also destroyed in the ensuing fire, but has now been recreated, albeit a little more forcibly, by a group of talented planters.

The Tsurugajo Castle in Aizu-Wakamatsu, which was similarly devastated by the new government forces, was restored to its present appearance in 1890 (Meiji 23) when the former Aizu clan warriors donated their private fortune to acquire it and donate it to the former Matsudaira family, just before it was demolished.

If you look closely at this 'moon pine', you can see many things on the other side of the circle of pine trees.

I visited the actual location of my favourite 100 views of famous places in Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like nowadays.

I visited the actual location of my favourite 100 views of famous places in Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like nowadays.

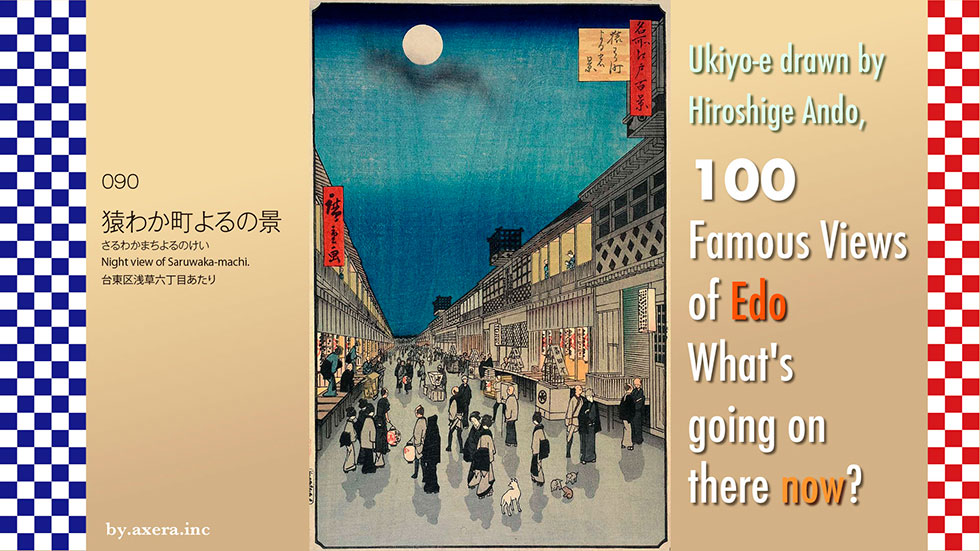

The 090 'Night view of Saruwaka-machi' is a view looking towards Kototoi-dori from Asakusa 6-chome, which was called Shibaimachi in this period.

First of all, please note where this location is depicted. If anything, it is on the north-eastern outskirts of Edo, around the north-eastern side of what is now Asakusa Station.

See a slightly enlarged map. I have added a red gradation, Hiroshige's point of view, to it. The scale is a little different, but let's put a map from the Tempo period on top of it. The area indicated by the red gradient was a theatrical town called Saruwaka-machi.

Please see the detailed map of this Saruwaka-machi up to the 2nd year of the Ansei era. Again, I have included Hiroshige's viewpoint in a red gradient. The entire town was occupied by shibaigoya (playhouses), shibai teahouses, residences of people involved in the theatre and related facilities.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's paintings. First of all, at the top is the moon on the fifteenth night. So it is a view of an autumn night. It depicts Edo citizens returning home outside after a Kabuki performance at the end of the evening.

On the right are the three kabuki houses known as the Edo Sanza, in the order Morita-za, Ichimura-za and Nakamura-za. Above each entrance is a signboard called a "Yagura(Watchtower). It was customary to put up a curtain on three sides, with five hair spears and a Brahma doll on the side, as evidence that the performance had been authorised by the shogunate.

The row of shibai teahouses on the left were for drinking and eating after the play had finished, and were usually open until midnight. Alongside these were the Yukiza and Satsumaza, two puppet theatre houses.

If you look closely, you can see a customer who has prepared to go home and is about to board a palanquin, and a woman from a teahouse is politely escorting him back to his palanquin. The sushi stall on the right is probably about to make another fortune.

The teahouse is already lit, and the theatre-goers, who look like a family of samurai, are about to go somewhere, following a guide man with a lantern under his arm.

The Edo Sanza moved into this location in 1841, just as Hiroshige was reaching the peak of there career when he painted this picture.

To see a play in Saruwaka-machi from the Takadanobaba area, people had to get up in the middle of the night, cross the Ushigome area, change to a boat and go down the Kanda River and the Sumida River. Therefore, if you returned at the end of the night, you would usually arrive at midnight.

The origin of Kabuki is said to be Kabuki Odori, which was started around 1603 by a woman called Izumo no Okuni in Sanjo-kawara, Kyoto. At this time, the dances often contained sexual scenes, and it is said that the possibility that Okuni herself had a prostitutes' side cannot be ruled out.

Later, the lustrous dances were adopted in prostitutes' houses and came to be known as 'prostitutes' kabuki', and spread throughout the country over a period of ten years or so. In parallel, there was also 'wakashu kabuki', performed by boys aged between 12 and 18, and 'yaro kabuki', performed by adult men only.

Around the time of the Genroku era (1690s), a notable actor appeared in this 'yaro kabuki'. He was Ichikawa Danjuro I of Edo, who gained a reputation for performing rough art. From this 'yaro kabuki', the modern form of kabuki was established.

Restrictions imposed by the shogunate also led to the liquidation of the many shibaihouses, and by the beginning of the Enpo era (1670s) only four - Nakamura-za, Ichimura-za, Morita-za and Yamamura-za - were authorised to operate as government-licensed shibai-houses, with their turrets raised as a sign of their status. However, an incident occurred here.

In 1714 (Shoutoku 4), Ejima, an old woman in the service of the birth mother of Ietsugu, the seventh shogun of the Tokugawa family, saw Ikushima perform at the Yamamura-za theatre, a playhouse in present-day Higashi-ginza, on his way back from visiting the former shogun's grave at Kan-eiji in Ueno and Zojoji in Shiba. At the banquet that followed, Ejima invited Ikushima and others to his teahouse, which caused him to be late for the curfew in the inner palace. This became a major problem within the shogunate, and Ejima was imprisoned for the next 27 years, while the actor Ikushima was exiled to Miyake-jima and the Yamamura-za theatre was also destroyed. The incident became a topic of conversation throughout Edo, and was painted and performed in Kabuki theatre.

Originally, the magistrate's office had a policy of preventing the proliferation of playhouses by banning prostitutes' and young people's kabuki on the grounds that it disturbed public morals, and by granting the right to perform to yaro kabuki on a licence basis. As a result, the number of playhouses in Edo was gradually reorganised, and only three - Nakamura-za, Ichimura-za and Morita-za - were allowed to 'raise the Yagura(Watchtower)', which were known as Edo sanza (Edo three theatres).

Another incident occurs on 7 October 1841. The Nakamura-za theatre was destroyed by fire, and the Ichimura-za theatre burned down in a similar fire. Together, the Satsumaza and the Yukiza puppet theatre also suffered damage.

At the same time, the Tempo reforms were being promoted in the Shogunate under the leadership of the old chief of staff, Mizuno Tadakuni. Kabuki actors such as Ichikawa Danjuro VII were banished to Edo for their extravagant costumes, and playhouses were placed under near-repressive control to show the citizens of Edo what they could do.

Incidentally, Ichikawa Danjuro Hakuen, who is scheduled to Imperial tour of succession perform in the autumn of this year, is the 13th Ichikawa Danjuro.

The incident prompted the Shogunate to forbid the playhouse from being rebuilt in the same location as part of a gag law, and the following year it was forcibly relocated to the Asakusa Shoden-cho area (now part of Asakusa 6-chome, Taito-ku, Tokyo). In addition, the Morita-za theatre in Higashi-ginza was also forced to relocate.

This newly established theatre town in a remote area far from the centre of Edo was named Saruwaka-machi after Kanzaburo Saruwaka, the original founder of the Nakamura-za family, but it was so remote that it did not attract any customers in the early days. Later, it gradually became popular thanks to the exchange of actors between the Edo three theatres and promotion. Eventually, together with visits to the Senso-ji temple, the Yoshiwara play after seeing a play, or the execution at Kozukappara in Minami Senju, the Asakusa area grew into a major entertainment district reminiscent of Ningyocho in the olden days. Hiroshige depicted Saruwaka-machi at its most vibrant at this time.

I actually went to the current Saruwaka-machi. This is the view that Hiroshige once painted. The scenery is completely far removed from the bustle of the city, with houses and small and medium-sized office buildings lining the streets.

When the shogunate collapsed at the end of Keio 3 (1867), ten years after Hiroshige painted this place, the new government suddenly recommended at the end of September the following year that the Edo Sanza in Saruwaka-machi be relocated elsewhere as soon as possible.

The first theatre to leave Saruwaka-machi was Morita-za, which moved to Shintomi-cho in 1872 (Meiji 5) and was temporarily acquired by Shochiku, but was damaged by the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 (Taisho 12) and closed.

Next was Nakamura-za, which moved to Torigoe in 1884 after a fire in 1882, but was completely destroyed by fire in 1893 and closed down.

The last Ichimura-za was moved to Taito 1-chome in 1892 (Meiji 25), and Shochiku took over the management for a while, but it was destroyed by fire in 1932 (Showa 7) and closed down. The Edo Sanza, which boasted a 300-year tradition, finally drew the curtain on its history.

Today, not even the name of the town of Saruwaka-machi remains.

The Nakamura-za theatre in Saruwaka-machi, which was at its most vibrant at this time, has been lavishly restored at the Edo-Tokyo Museum in Ryogoku. This will surprise you to see what it was like back then.

The present-day view is inset into Hiroshige's painting. The town is so quiet that it is hard to believe that it was once a busy theatre town.

In those days, there was no reliable lighting, so plays were performed from morning until dusk. The only light was from the outside, as it was in a dimly lit hut. Today, however, lighting, staging and stage construction are more elaborate, and the plays can be seen in bright conditions as a comprehensive performing art. Kabuki also continues to make various other developmental attempts, such as incorporating somersaulting and taking material from manga as a modern form of theatre, while still placing emphasis on tradition.

In the Edo period, entertainment, whether kabuki or sumo, could only be enjoyed by going to the place where it was performed, whereas today, although not as realistic, the content can be enjoyed in the comfort of one's own home. Now I would like to think about whether this is a good thing or a bad thing, while looking at the current situation here in Saruwaka-machi.