I visited the actual location of my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scene looks like today.

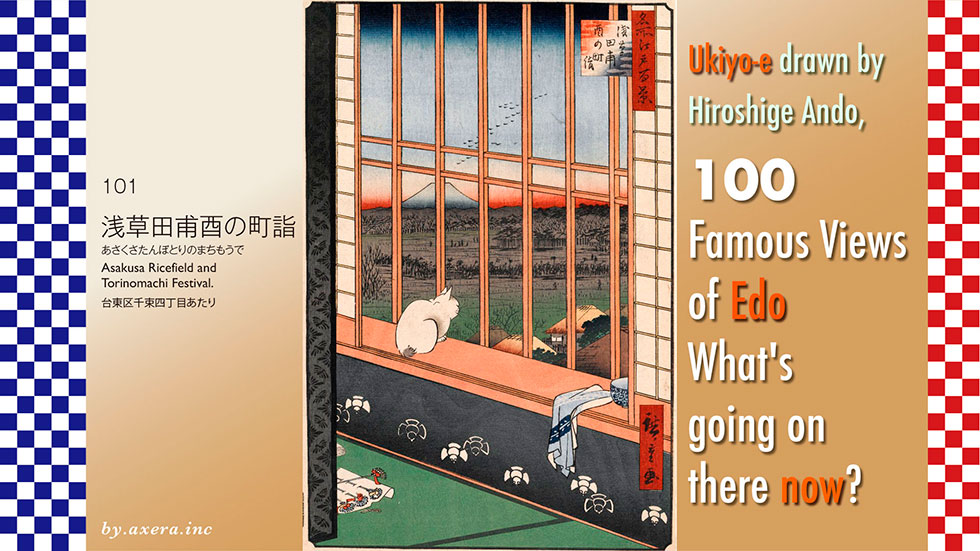

In "Asakusa Ricefield and Torinomachi Festival", the Otori-sama and there visitors are seen from a room of a brothel in the Shin-Yoshihara licensed quarters.

First, please check where Shin-Yoshihara was located on Applemap.

It is about 5 km northeast of Edo Castle. At that time, this area was on the outskirts of Edo, and there were few private residences, mostly fields and rice paddies.

In 1617, shortly after the establishment of the Edo shogunate, a recognized brothel called Yoshiwara was permitted in the area around present-day Nihonbashi Ningyocho, but it was destroyed by the great fire of Mereki (1657). The Shogunate then relocated the brothel to rice field, behind Sensoji Temple, instead of rebuilding it, because the Ningyocho area had already become quite residential.

This new officially recognized brothel was called Shin-Yoshihara to distinguish it from Yoshiwara in Ningyocho. It is represented by the red dashed line on the map.

Here is a slightly enlarged map. Shin-Yoshihara, with a total area of 20,700 tsubo, was rectangular in shape, surrounded on all sides by blackboard walls that isolated it from the rice fields outside, and on the outside by a 3.6 meter wide moat called "o-haguro-dobu". The moat was built to control suspicious persons and prevent prostitutes from escaping. It is the blue line.

The only entrance and exit to Shin-Yoshihara was the O-mon gate on the northeast side.

On top of this, I will cover a pictorial map of the time.

However, it is too small, so if you enlarge it a little, you can see the relationship between Shin-Yoshihara and Ohtori-jinja Shrine.

This is a detailed map of Shin-Yoshihara from 1846 (Koka 3), with the Ohm gate on the right. You can see that the stores are crowded together.

Next, please take a look at a map called Saiken-zu, issued in the fall of the 4th year of Ansei (1854). This is a map of the period when stores were newly moved into Shin-Yoshihara, which had been rebuilt after a fire caused by an earthquake, from temporary stores scattered all over Edo City. The Ohmon gate is shown below. Guide map-like maps like this one were best sellers at the time.

Hiroshige's drawing may have been made with the rooms of the big stores around Ebiya and Miuraya, surrounded by the red dashed lines, in the upper right corner of the map.

Here we will look at the paintings of Yoshiwara left by Hiroshige and Kunisada, and explain Shin-Yoshiwara and the prostitutes who worked here.

This is the overall picture of Yoshiwara painted by Hiroshige. 10,000 people lived on this site, and as much as 1,000 ryo per day was spent there.

In addition, the shogunate required that 10% of the money be paid to the town magistrate, so Shin-Yoshiwara was highly valued, and the policing of the area was extremely strict.

Yoshiwara was a famous sightseeing spot and cultural center of Edo, and the prostitutes who behaved so glamorously were actually living a harsh life, known as "ten years in a bitter world. They were not allowed to leave Yoshiwara until they had completed ten or more years of hardship.

Most of them came to Yoshiwara as prostitutes. Since peddling was prohibited even in the Edo period, it was ostensibly a form of indentured servitude, but in reality it was mostly human trafficking. Recruiters called pedants traveled around the country, not only looking for offers from relatives, but also for daughters of poor peasants to seduce their parents and bring them to the brothels with sweet words for their daughters.

Rural daughters were sold by their parents for a mere 3 to 5 ryo, or less than 400,000 to 1 million yen in today's value. These debts became their own debts, and since they were charged enormous interest, they could not easily repay them and had to serve 10 years of indentured servitude. The prostitutes received only two holidays a year, New Year's Day and Bon Festival (July 13). Even then, however, most of them were not free to leave the Ohmon.

In 1849, an attempted arson attack occurred in which 16 prostitutes of Umemoto-ya conspired to set themselves on fire. In the commotion, the women rushed to the house of the master and accused the management of wrongdoing. In their written statements, they described their horrific daily lives, including being fed only rotten rice and being chastised to the point of near-death.

There were approximately 3,000 to 5,000 prostitutes in Shin-Yoshihara, but only a few high-class prostitutes were called "tayu" or "yobidashi.

Most of the prostitutes died of venereal diseases before the end of the year, or were unable to repay their debts and were stuck in Yoshiwara for the rest of their lives.

It is believed that the average life span of a prostitute at that time was about 22-23 years old.

The only time a prostitute could leave Shin-Yoshihara was when she died. The bodies of prostitutes were secretly hung upside down in the middle of the night and carried out of Yoshiwara. The bodies were usually brought to the precincts of several "nagekomi-dera" temples, such as Jokanji Temple in Minowa and Saiho-ji Temple in the Imado area under the Nippon Zutsumi, and left there with a small coin attached.

According to the records in the Jokan-ji temple's past records, the average number of bodies of prostitutes brought in from Shin-Yoshihara in a month was about 40, and 28 at Saihoji temple.

The world was warmly receptive to the prostitutes who had overcome the glamorous and miserable conditions of their lives and had come to the end of their years.

Here is an episode. Kyoden Santo, a writer who is said to be the most typical of Edokko, got married twice in his life, both times to ordinary prostitutes who were not in the oiran (courtesan) class. On one occasion, Kyoden told his younger colleague Takizawa Bakin, the famous author of "Nanso Satomi Hakkenden" ("Eight Dogs of Satomi"). All of them are kind, intelligent, and the best for wives.

Let us take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

Geese fly across the still blue sky. Fuji, covered with snow on the horizon, and the darkly painted rice field below it. If you look closely, you can see many people carrying rakes. The source of the procession is Ohtori-jinja Shrine, which is hidden on the right.

The Washi-jinja Shrine (Ohtori-jinja) was called "Tori-no-machi", with its annual festival on the day of the rooster in November, and was crowded with merchants and craftsmen who prayed for prosperous business, selling rakes to "bring in profits", yatsugashira-imo (sweet potatoes that "can become human heads") and golden rice cakes (chestnut cakes) to "make you rich".

On this day, which was also a special holiday in Shin-Yoshihara, the Nishigashi gate at the far end, which was usually tightly closed, was opened, and a hastily made bridge was built over the ohaguro dobu, allowing free entry and exit if accompanied by a guest.

The black impulse on the far left depicts a crest called a toridasuki, depicting it as a dignified store. On the waistboard, a puffy sparrow is depicted, ironically expressing the wish that the owner will not have trouble finding food and that he will live a prosperous life.

In the lower left corner are several rake-shaped hairpins, probably purchased from Otori-sama. In fact, "kanzashi" were very popular in Yoshiwara at that time as a lucky charm to attract customers, and various designs were made and used to communicate with customers. Keisai Eisen depicted such annual events.

In the center is a white cat staring out of a latticed window. The cat is probably a prostitute's pet, but to me, it looks like a prostitute itself.

The master is hard at work behind the blinds, but the cat is staring out as if nothing is going on.

Now, I have actually been to this location. However, this location has not been precisely assigned. This picture shows the northwestern edge of the former Shin-Yoshihara, at the fork in Senzoku 4-chome. If you go ahead, you will find the Ohtori-jinja Shrine.

This is the present-day Ohtori-jinja Shrine. Until the Edo period (1603-1868), the shrine was the Washi-Daimyojin, a precinct shrine of Chokokuji Temple, but became independent upon the separation of Shinto and Buddhism during the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912), and the name was changed to Ohtori-jinja Shrine.

The deity is Amida on the back of an eagle, which is connected to "grasping the eagle," and was popular as a god of success in life, military fortune, and good fortune. Nowadays, though, the shrine is surrounded by buildings rather than in Ricefield.

I tried to fit the current state into Hiroshige's painting.

This is the state of the painting for now.

This is too different from the original, so I made a composite of Applemap, GoogleEarth, and Mt.Fuji.

Now I believe that Hiroshige wanted to support the prostitutes as a whole with this painting.

This painting was issued in November of the fourth year of Ansei (1857). Shin-Yoshihara, which had been destroyed by the Ansei earthquake just two years earlier, began full-scale reconstruction and relocation in June, and was just beginning to bustle with activity around this time. More than 500 prostitutes were killed in the earthquake, but those who were lucky enough to survive returned to Shin-Yoshihara and began to work hard to make it through the year.

The toridasuki pattern on the impulse stand in the painting and the puffy bird of a sparrow signify the "caged bird" status of the prostitutes, and the white cat in place of the prostitutes stares out, dreaming of eventually going outside to collect good fortune with its rake-shaped hairpin. Perhaps I am overthinking it, but I feel that this painting represents at least the wish of Hiroshige, who had shaved his head and become a monk the year before.

I actually visited the location of my favorite "One hundred Famous Views of Edo" painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scene looks like today.

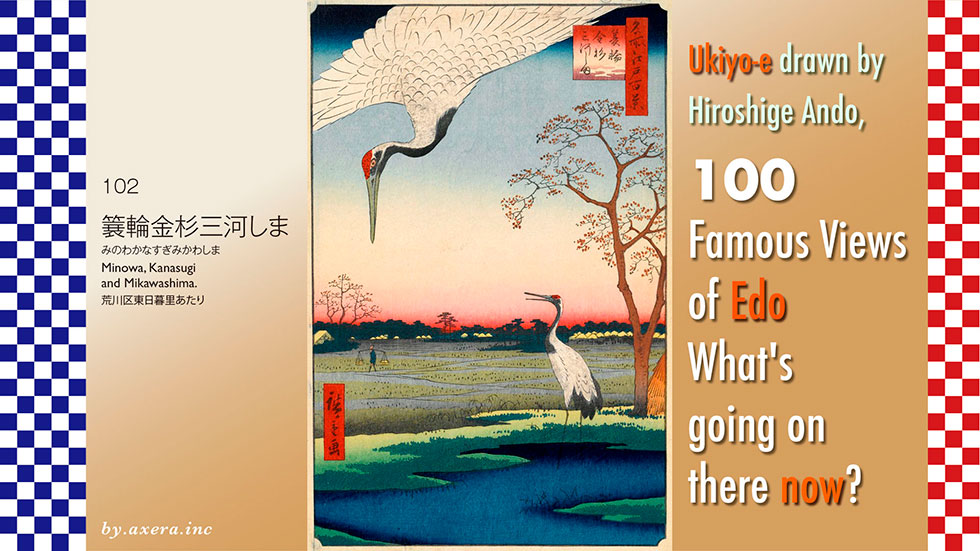

The 102nd, "Minowa, Kanasugi and Mikawashima," depicts a red-crowned crane that used to live around present-day Minowa and Mikawashima, and the view of the area.

It is said that Hiroshige painted this picture around the south side of the area between the current Minowa and Mikawashima stations, but even researchers do not know the exact location. The map shows this location with a red dashed line.

I believe that the view is from Higashi-Nippori 3-chome looking east, based on comparison of various old maps of the time. The red gradient is shown below.

Please refer to the map of Tokyo History Map around the time of the Tempo Era. Originally, Mikawashima and Kanasugi villages were located in this area, which was a frequent source of flooding overflowing with water from the Sumida River. The wetlands and abundant food supply were very favorable for birds, and many migratory birds gathered here in season. You can see many puddles that look like reservoirs on the map.

Now we will actually take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

This painting was published as a winter painting in May of 1857.

A red-crowned crane is depicted as if covered from above, and what appears to be a village is depicted in the distance below it. I suspect that this is a house along the Nikko Kaido.

To the left is a slightly larger house, and beside it is depicted a man carrying a balance pole on his way to it. This man was the caretaker of the cranes here, feeding them and taking care of them.

Originally, successive shoguns of the Edo shogunate liked to go falconry for training in martial arts. This area in particular was a great place for falconry, as there were wetlands all over the area. The shoguns would come from Asakusa and visit Kozukahara, Hashiba, Minowa, Mikawashima, and Machiya.

Furthermore, cranes used to migrate to this area every October. Since cranes were prized as a sacred bird of good fortune and longevity in those days, a feeding ground for them was set up here, and the shogunate strictly controlled the area around the feeding ground with bamboo barbed wire and straw to prevent humans and dogs from entering. The man on the left is thought to be the "Torimi-no-Nanushi," or "Inuban(dog guard)," who was in charge of managing the area and watching for wild dogs.

Although cranes were cherished, only once a year in December, a falconry called "Tsuru-Onari" was held, in which the shogun would catch two cranes. Each hunted crane was put into a white wooden box and sent to the emperor and the crown prince in Kyoto by express mail as a good-luck gift.

Now, cranes are often referred to as red-crowned cranes in Japan. According to ancient Chinese legend, the crane was a bird that lived in the fairyland, but in the Edo period, crane meat was prized as a luxury food along with swans. The Matsumae clan in Hokkaido exported them overseas as "salt cranes. However, this seems to have been either manazuru crane or nabezuru crane, and the meat of the red-crowned crane was actually tough and not very tasty.

Cranes caught by the Shogun's hawks were called "Okobushi no Tsuru," or cranes of the fist, and were presented to the court, so cranes were considered a bird for the upper class to handle. In fact, Toyotomi Hideyoshi had crucified a person who captured a crane, and the common people believed that capturing a crane was a capital offense.

After the fall of the Edo shogunate, the cranes entered a period of great hardship. Hunting of cranes, which had been forbidden until then, became widely practiced among the general public, and overhunting proceeded at a tremendous pace. As a result, the red-crowned crane was thought to be extinct in Japan until it was rediscovered in the Kushiro Marshlands in 1924.

In 1935, it became a national natural monument, including its breeding grounds, and in 1967, it was designated a special natural monument as a species without a defined area. According to a Hokkaido Government survey, as of January 2021, 1,516 cranes had been confirmed, including those in captivity. As a red-crowned crane, this is a relief.

Well, I actually went to this place. I went to the intersection of Higashi-Nippori, which I had guessed on my own that it would be in this area.

This is the picture looking toward Mikawashima Station.

This is the picture looking toward the nightingale station.

The current view is incorporated into Hiroshige's painting.

Well, this is good, but I also inset another picture of a red-crowned crane in Kushiro.

In fact, groups involved in the publication of Ukiyo-e were restricted in several ways by the shogunate. If there was even the slightest problem, the publication of Ukiyo-e was immediately banned, and the prints had to be recalled.

For this reason, it was essential for Hiroshige and other artists to be considerate of the shogunate by faking the number and visibility of military installations such as daiba when depicting the Shinagawa area, and hiding places such as armories and ammunition depots on the sides of Edo Castle with haze clouds.

On the other hand, the Shogun would capture two cranes, a sacred bird whose capture was punishable by death, each year by falconry and send them to the palace. From the perspective of the cranes, this meant that instead of being cherished and cared for, the shogun offered two cranes as sacrifices each year.

Crane is the English word for crane, which is the origin of the word for crane, that heavy equipment used to lift heavy objects. The word "pecker" is also derived from "crane's beak," in Japan which is a tool used to break up hard ground.

In this painting, what kind of heavy object was Hiroshige trying to lift up and what kind of hard object was he trying to smash?

Exactly 10 years after the publication of this painting, the Edo Shogunate decided to return to the Great Government.

I visited the actual location of my favorite "One hundred Famous Views of Edo" painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scene looks like today.

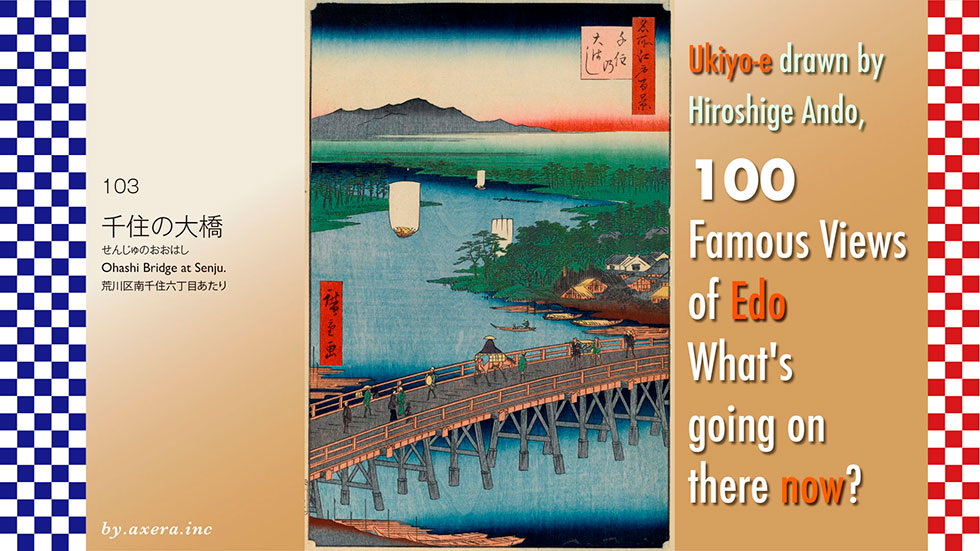

The "Ohashi Bridge at Senju" of 103 is a view of the Arakawa River upstream from the Senju Ohashi Bridge.

First of all, please check where this Senju Bridge is located on the map.

The bridge spanned the Arakawa River, which flowed about 7 km north-northeast of the Edo Castle keep, just beyond Minami-Senju Station. At that time, the Sumida River was called the Arakawa River in this area.

Please see a slightly larger map. Hiroshige seems to have looked northwest from a slightly overhead view from downstream, just before crossing the bridge. This is indicated by the red gradation. You can also see that the road running vertically from the bridge to the south is split in two in the middle.

Please see an old map from the Edo period, the year this painting was made. The blue road is the Nikko Onari-kaido road and the red road is the Oshu-kaido road, which merge before the bridge and cross the Senju Ohashi Bridge.

Furthermore, please see the "Rekichizu" which represents the road around 1840. Today's Chuo-dori, which runs northward from Nihonbashi in the blue circle, passes through Sujichigai-gomon gate and becomes National Route 4 from Ueno to Minami-Senju, which is Nikko-Onari Kaido.

On the other hand, the Oshu Kaido turns to the right from around the current COREDO Muromachi area, becomes Route 6, and heads north along the right bank of the Sumida River to Minami-Senju.

These two roads merge, pass through Senju-shuku, and split into three at the end of what is now Kita Senju, just before what is now the Arakawa River. On the left is the Nikko Kaido, on the right is the Mito Kaido, and straight is the Shimozuma Kaido.

Please see the "Rekichizu" for a further enlargement. The Arakawa River, over the Senju Bridge, led upstream to Kawagoe at the Shingishi River, further upstream to the Iruma River, and further upstream to Chichibu.

From the Kawaguchi area, it was connected to the Minuma-tsusen, which passed through what is now Omiya, and then to the Moto-arakawa and Tone Rivers.

This diagram shows the river bank, or river port, that was located on the Shinkagishi River. You can see that Senju supported the prosperity of Edo as a relay point for the Kawagoe night boats, which connected Kawagoe and Edo overnight and carried rice, barley, firewood, coal, and fish along with passengers.

The Ayase River also flows into the river a short distance ahead of Senju, indicating that the Senju riverbank was a very important transportation hub where people and goods flowed together.

Now, let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

The first thing that appears is where the Arakawa River ends, the Chichibu mountain range. According to expert books, it is the Nikko mountain range, but it is clearly the Chichibu mountain range in terms of direction.

The Arakawa River occupies most of the screen, and downstream it changes its name to the Okawa River and the Sumida River.

On the left side of the screen is Machiya Village, and on the right side is Kitasenju, and just after crossing the bridge is Hashido-cho. Here, there are many boats moored along the riverbank. The remnants of the market are still in operation today.

On the left before the bridge is Minami-Senju and Kozukabara-cho. You can see lumber brought from Chichibu moored to the bridge. The bridge depicts people crossing on horseback, in palanquins, and with luggage on their backs, showing how the traffic was active.

This Senju village has long been considered a strategic location for water transportation, and has been involved in the struggle for its rights since the Muromachi period (1336-1573). After the conquest of Odawara in 1590, Tokugawa Ieyasu came to Edo, and the Five Routes were built. After the construction of the Senju Bridge across the Arakawa River in 1594, the area developed rapidly.

Hiroshige published a similar composition in his picture book Edo Mirage.

At first, the Edo shogunate did not allow bridges to cross the various Kaido into Kan-Hasshu centered around Edo Castle to protect the city, but the Senju Ohashi Bridge was built across the Arakawa River only at Senju-shuku.

The Senju Ohashi Bridge was repaired six times, but from the first bridge to the flood caused by a typhoon on July 1, 1885, the bridge had never been washed out, and is said to have been a famous bridge that survived nearly 300 years of the Edo Period.

The first bridge was built by Ina Tadatsugu, head of the Kanto district government, and the timbers were donated by Date Masamune from the southern part of the Rikuchu region and made of Koyamaki (Japanese umbrella pine), which is water-resistant and resistant to decay. Legend has it that the bridge survived until it was washed away by a flood in 1885, thanks to the Koyamaki trees. In fact, even after the bridge was washed away, local residents continued to collect the piles of Koyamaki and use them to make braziers and Buddhist statues to be worshipped as guardian deities. Subsequent research has confirmed that these KoyaMaki bridge piles remain under the Senju Bridge, proving that the legend was true.

Senju Aomono-Market, which was said to have begun during the reign of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, was already operating as a market by the Meireki era (the reign of Tokugawa Ietsuna). With the construction of the Senju Ohashi Bridge, the market became a relay point for agricultural products and river fish, and by the Kyoho era (the reign of Yoshimune Tokugawa), various goods were being gathered and shipped, and by the end of the Edo period, agricultural products from the Musashi, Kazusa, Shimousa, and Hitachi areas were also gathered.

Thanks in part to the construction of a bridge, Senju as an inn was the starting point of the Oshu-kaido and Mito Kaido routes, and was crowded with travelers heading for Nikko and Tohoku. By Hiroshige's time, Senju had become one of the largest inn towns in the four Edo districts, with 1 main inn, 1 side inn, 55 inns, and approximately 2,400 houses, and a population of approximately 10,000 people.

According to a survey conducted in 1821, a total of 64 daimyo on their way to and from Edo used Senjujuku as a stopover on the Nikko, Oshu, and Mito Kaido routes.

I actually visited this location.

This is a picture of the current Senju Bridge for downstream only, seen from the Minami-Senju side.

The main body of the bridge was replaced in February 1973, and the bridge for exclusive use of upstream is parallel to the bridge on the right side. On the left side of the photo, there is also a bridge dedicated for industrial water supply by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Bureau of Waterworks.

This is the view from the bridge looking toward Minami Senju. There is Susanoo Shrine ahead, and since the Senju Bridge was first built, the ritual of the great tug of war began and continues to this day.

This is a photo looking north from the up-only bridge. The bridge immediately separates the two lanes going down to the Minami-Senju intersection and the two lanes heading toward Ueno from the Senju Police Station traffic light. In front of the photo is Adachi's fruit and vegetable market, which still remains.

This is a photo looking toward Minami-Senju from the sidewalk side of the up-only bridge. The left lane turns left at the Minami-Senju traffic light and heads toward Asakusa on the old Oshu-kaido road. The elevated lane on the far right is the old Nikko Kaido, Route 4, heading toward Ueno.

Across the Senju Ohashi Bridge, the Senju Green Produce Market has changed its name to Adachi Market and is still in operation as a Tokyo Metropolitan Government facility.

At the end of Adachi Market, there is a stone statue and a monument to Matsuo Basho, who left from Senju Bridge with his disciple Sora on the Okunohosomichi (Narrow Road to the Deep North).

Please also see the first part of Yosa Buson's "Okunohosomichi," which is a picture scroll of the "Okunohosomichi. It begins with the sentence, "The months are eternal travelers, and the years that come and go are also travelers.

Although the direction is slightly different from Hiroshige's painting, please also see the picture of the changed north side of Edo, seen from the sky above the Senju Ohashi Bridge downstream on the east side.

I inserted a bird's eye view of google street view into Hiroshige's painting.

Senju Ohashi Bridge was not only the setting for Matsuo Basho's departure, but also the bridge from which the last shogun of the Edo Shogunate, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, left for Mito.

In the early morning of April 11, 1871, 12 years after Hiroshige published this painting, the Senju Bridge was crowded with people and bannermen who were in love with Yoshinobu Tokugawa in the deep morning fog. When Keiki eventually appeared with a few companions, he saw Tesshu Yamaoka prostrate himself on the spot and called out to him, "I will not forget the cause of the emperor even after I leave my estate in Mito.

Hearing these words, Tesshu Yamaoka said, "You have put up with me well," and Yamaoka sobbed on the spot, apologizing for the many disrespects he had shown to Yoshinobu.

Satcho, who had supported the Imperial Court and staged a coup d'etat, wanted to make war on the Shogunate, making it the enemy of the Shogunate. The main warlords on the Shogunate side also wanted to confront Satcho. However, Yoshinobu heeded the advice of Tesshu Yamaoka, and decided to leave Kan-eiji Temple in Ueno and stay at his estate in Mito, in deference to the Imperial Court and to be patient. This was to avoid the firestorm that was about to engulf Edo.

If someone like Tesshu Yamaoka had been in what is now Russia and Israel, times might have been a little more peaceful.

This year marks 434 years since the first Senju Bridge was built.

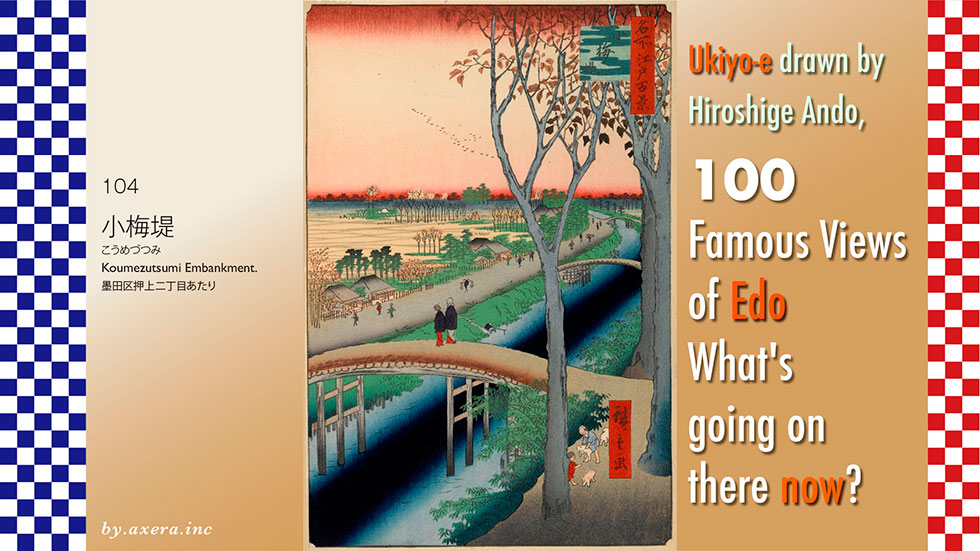

I visited the actual location of my favorite "One hundred Famous Views of Edo" painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scene looks like today.

The 104th "Koumezutsumi Embankment." depicts a view of the Hikifune River, which used to flow behind the current Tokyo Skytree.

First, please check the location on a large map.

It is about 5 km northeast of Edo Castle, around where Tokyo Skytree Station is now located.

Here is a slightly more enlarged map. The Kifune River flowed from the northeast into the KitajukkenRiver, which used to flow east-west south of the Sky Tree. It is shown by the blue line. Hiroshige painted the view around this curve. The viewpoint is represented by the red gradation.

This is what it looks like in Street View. Hiroshige's viewpoint is a yellow gradient.

This is the street view from the viewpoint direction.

The blue line represents the Hikifune River, which has now been reclaimed and turned into a road.

This Hikifune River was constructed by the Shogunate in 1659 for the development of Honjo. At that time, it was called Honjo-josui or Kameari-josui, and water was distributed and supplied from Moto-arakawa River in what is now Koshigaya City to various parts of Fukagawa.

Later, in 1722, the river ceased to serve as a waterway, but it came to be used as an important transportation route as the Yotsugi Kaido passed by the riverbank and connected to the Mito Kaido.

The river became known as the Hikifune River because travelers were pulled from the shore in boats called "zappako," and Hiroshige depicted this scene in his 33 Views.

Now here is the Tokyo History Map2. The base GSI map is covered by a map of the time.

Koume-village in the viewpoint is called Umegahara, an area with many plum trees, and Koume Kawara-cho in the east, like Imado-cho across the Sumida River, was named after the many kilns where tiles were baked.

In addition, there are Oshiage, Ukeji, and Terashima villages around the viewpoint. Oshiage is a village where the ground was pushed up, Ukeji is a floating island that became a Ukeji land, and Terashima is an island (shima) with a temple (tera), all place names symbolize this area that was a source of flooding. In fact, the Arakawa River joins the Iruma River and the Shingashi River and flows through this area in many different directions, and it seems that people lived on land other than the reed-lined marshland. The map shows many remaining blue ponds.

Hiroshige left a painting with a slightly different direction in his picture book Edo Souvenir 7. Reading the explanation of the book, it seems that this area was a favorite of Hiroshige. The guardian deity of this Koume village is the Mimeguri Shrine, and a little further down the road is the Akiba Shrine, famous for its fire protection. As a sightseeing spot, it seems to have been a place where visitors could easily reach from Asakusa.

In the Honjo Koume area, there were many restaurants and teahouses that catered to visitors to the temple. Hiroshige depicted one such establishment as a restaurant guide of the time.

In front of a large building that appears to be the main building, private rooms for entertaining guests are lined up in a row, and a woman is playing fishing in a small covered boat.

Now, let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

The painting depicts geese flying across a winter morning sky, and a tree with brown leaves halfway across the sky. This is an alder tree, planted to protect the irrigation channel. The same tree is also planted in the rice field in the back, which was used in place of a rice rack to dry harvested rice and other crops in the fall.

The Hikifune river curves to the left, but is actually almost straight. The next bridge to the left of the last bridge seen in the picture is the Akiba Shrine. In the picture, it is the small roof surrounded by green forest on the far left.

The road running parallel to the Hikifune River is the Yotsugi Kaido, which depicts many travelers. Straight ahead was Mito Kaido, and turning right before it led to Taishakuten in Shibamata. A tea store for these travelers is also depicted on the left.

On the bank beyond the two samurai-like figures crossing the bridge in the foreground, a villager is depicted leisurely casting a fishing line. Across from them, on the left bank, are many bamboo grass plants. Like the alder, they were planted to strengthen the embankment of the Hikifune River.

If you look closely, you can see that the two alder trees on the right side are laughably large and exaggerated. The child and dog playing at the base of them are cute. It is typical of Hiroshige to depict the lifestyle of the time in this area.

I have actually been to this location.

Today, the river has been reclaimed and turned into a road called Hikifune-dori.

A little further forward, the buildings along the road seem to be leaning against each other. The large high-rise building seen at the end of the road is the redevelopment area in front of Keisei Hikifune Station.

I tried to fit the current image into Hiroshige's painting. The river has become a road, the road is wider, and buildings have been built, so there is not even a trace of those days.

The road crosses the Arakawa River at Shin-Yotsugi Bridge and becomes a water park, passing by Ohanajaya and Kameari Stations, and from Oyata, a waterway called Kasai Waterway is restored. The waterway continues on, passing west of Koshigaya Lake Town, and still connects to the former Arakawa River.

In fact, "Koumezutsumi Embankment." is not included in Edo Meisho Zue, a book that introduces all the famous places in Edo. What is now known around the world as the Tokyo Sky Tree may not have been so famous at that time.

Until now, Hiroshige has half-heartedly depicted his favorite Mt. Tsukuba in this series, even if it is not visible. Even in the 33rd view looking in the same direction, Mount Tsukuba is depicted in large size. However, Mt. Tsukuba, which should be clearly visible in the foreground, is not depicted in this series.

This raises the suspicion that Hiroshige may have painted this picture just to make up the numbers.

See, Mt. Tsukuba was supposed to be drawn like this, but Hiroshige forgot to write it down?

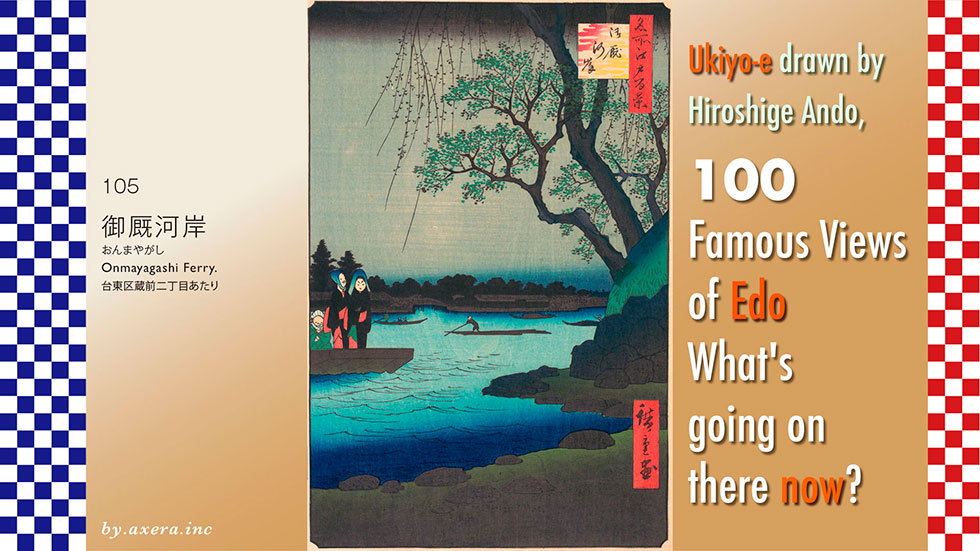

I visited the actual location of my favorite "One hundred Famous Views of Edo" painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scene looks like today.

The "Onmayagashi Ferry" in #105 depicts a night scene of a ferry crossing of the Sumida River that departs from and arrives at the Onmaya Riverbank, a little downstream of the present-day Umayabashi Bridge.

Please first check where this place was located.

It is located about 1 ri (about 4 km) northeast of Edo Castle. The area is surrounded by a red dotted line.

Please see a slightly enlarged map. In the Edo period, there were no bridges in this area, and there was a ferry on the Sumida River between Kuramae-bashi and Umaya-bashi bridge, that carried people to the other side of the river by boat. This is indicated by the red dashed line.

Let's cover this with a map of the time.

The right bank of the Sumida River in this area was lined with warehouses for a distance of 700 meters. These warehouses, called "Asakusa Okura," were used to store the annual rice tribute paid to the shogunate. To the north, in Miyoshicho, there were stables for horses kept by the shogunate, and the ferry from and to these stables was called "Onmayagashi Ferry".

The location of Hiroshige's viewpoint is shown in red gradient.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

On the right side of the painting is an oak tree growing from the bank of the Asakusa Okura, with willow branches also hanging down from it. The whole scene has a mysterious nighttime feel to it. On the other side of the river is Honjo Ishihara-cho, and the bridge over the small moat is Ishihara-bashi bridge.

Since the Sumida River is the main distribution route, boatmen carrying rafts and boar boats carrying luggage and people are also depicted, and a ferry boat coming from the opposite bank on the left is approaching the shore. The two women with red sashes riding in a bow are Night hawks, and the man sitting on the left is a Night hawk's tout and protector, called "Gyu.

The ferry was designated as a ferry in 1690, and records show that there were eight ferry boats, 14 boatmen, and four watchmen. The fee was 2 mon (about 30 yen in today's value) per person, and there was no charge for samurai.

Hiroshige also depicted this "Onmayagashi Ferry" in his One hundred Famous Views of Edo in view 61. He depicted the "Onmayagashi Ferry" crossing from downstream over the "Pine of Success". This is a night view from the middle of "Asakusa Okura" looking upstream toward Azumabashi Bridge.

There was another ferry called Fujimi no Ferry on the Honjo side from the "Pine of Success". Katsushika Hokusai depicted this in his "Thirty-six Views of Mt.fuji. This is the view of Mt. Fuji from the opposite side of the river over the Ryogoku Bridge. As expected of Hokusai, it is a magnificent view.

Here again, please see the map.

Where did these nighthawks come from? This area was famous as a town where nighthawks lived, and they crossed the Sumida River from here to Kanda and Asakusa area to do business. The map of those days is shown on the Honjo side.

At the same time that Hiroshige was gaining popularity for his "One hundred Famous Views of Edo", his great friend Toyokuni Utagawa was gaining popularity for his series "One Hundred Famous Beauties of Edo". In his series, Toyokuni depicted women of the same sex and manners. On the left is a prostitute from Shin-Yoshihara, a brothel authorized by the shogunate, and on the right is a nighthawk accompanied by a "gyu. Night hawks were a type of street prostitute in the Edo period, prostitutes who came out at night and prostituted themselves in the open air or in temporary huts. They were always accompanied by a bouncer called a "gyu" to protect them from customers who ran away without paying or who made false accusations or were violent.

In the Edo period, the typical fee for a prostitute in Shin-Yoshihara was about 500 to 2,000 mon, or about 150 to 250 dollars in today's terms. On the other hand, the nighthawks on the right, the lowest class of prostitutes, painted white from the neck up, wore a cotton kimono with a hood over it, always held one end of the hood in her mouth, and carried a sheet of mats with her while performing sexual services in the open air. The fee for this service was 24 mon, which is about 4 to 8 dollars in today's value. Since the price was close to the price of a bowl of buckwheat noodles at that time, the customers were mostly low-paid laborers and low-ranking servants of samurai and merchant families.

I actually visited this location.

It seems that the Metropolitan Expressway Route 6 runs in front of the beautifully revetted Sumida River terrace, and the area around Lion's Honjo Research Institute, which is located after it, was the arrival and departure point for the Honjo side of the river.

A little further downstream, around here, is the start/finish point on the Sumida River right bank of the Omayagashi ferry.

Looking upstream, Umayabashi Bridge and the Tokyo Sky Tree can be seen beyond it.

I have tried to fit the current photo into Hiroshige's painting. I darkened the daytime photo to match only the atmosphere.

The main motif of Hiroshige's painting this time is nighthawks, and it is said that there were as many as 4,000 of them in Edo at that time. The night hawkers included women from poor families, women who had been prostitutes, and middle-aged women who were poor. They ranged widely in age, with some being as old as 70 years old.

Even though they were called prostitutes of the lowest class, they were a common sight in Edo, appearing here and there in the town at night. They were often policed by the shogunate under the name of "night hawk hunting" because they were unauthorized, even though they appeared with the same frequency as today's convenience stores. This was a form of bullying by the shogunate, which was unable to collect taxes from these women. On the other hand, Edo citizens seemed to look at them warmly as ordinary "working women.

If you look closely, you can see that both of the white-painted nighthawks have very humorous faces. We can feel Hiroshige's gentle gaze toward them.

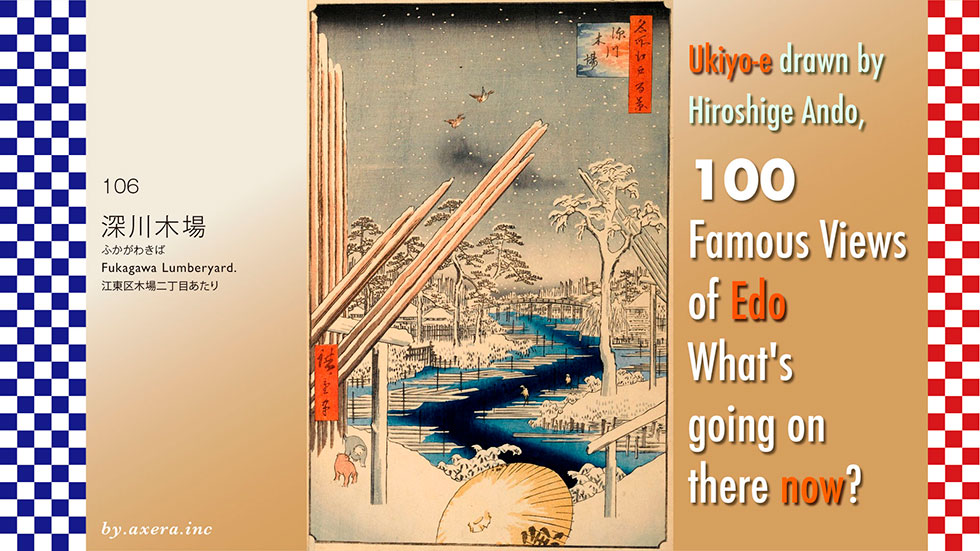

I actually visited the location of my favorite "One hundred Famous Views of Edo" painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scene looks like today.

It is not known exactly where the 106 "Fukagawa Lumberyardy" was painted. However, it seems that it depicts the moat of a lumber yard in the area called "Fukagawa Kiba" at that time.

Please check first where this location was located.

It is about 6 km east-southeast of Edo Castle. Although it is rough, I enclosed it with a red dotted line.

A slightly enlarged map shows the area around Kiba Station on the Tozai Subway Line. The area around Kiba Park on the north side of the station now appears to have been the center of a lumber yard at that time.

I covered this with a map of the time.

When the scale is adjusted roughly, many words "Mokuokiba" appear, indicating that this area was a lumber yard. The light blue dashed line indicates the location of the lumber yard.

In order to examine the area a little more precisely, let us cover the current map by the GSI with a map from around 1881. This also reveals the lumber yard that still remained at that time. It seems that almost the entire area north of the current Kiba Station was used as a lumber yard even in those days.

This is a sketch-like pictorial map known as the Keicho Edo Zu, drawn before and after Tokugawa Ieyasu's entry into Edo. Although it lacks directionality and accuracy, it is a valuable pictorial map of Edo as it was first drawn. Since this inlet was filled in 1603, it is estimated that this map may have depicted the townscape of Edo around 1602.

At the time, the Edo Castle built by Ota Dokan was in shambles, and Edo Bay extended into what is now Iidabashi, known as "Hibiya no Irie," with brackish marshes spreading throughout the bay.

Tokugawa Ieyasu entered Edo in 1590, and the first thing he began to do was to establish the Kanda Waterworks and develop residential areas. Specifically, he reclaimed marshland and secured water.

The Tokugawa Shogunate ordered the feudal lords of various regions to build urban areas in Edo, which led to the cutting down of mountains and the reclamation of inlets and bays, which in turn led to the rapid expansion of Edo as many samurai and their families took up residence and townspeople were also attracted to the area. Craftsmen and carpenters for civil engineering works were also gathered from all over the country.

This is a map of Edo drawn in 1690. This was the era of Tsunayoshi Tokugawa.

The Kanda Waterworks and Tamagawa Waterworks were completed, development of the Honjo Fukagawa area was underway, and the population exploded. However, since buildings at this time were almost exclusively made of wood, fires broke out frequently, and lumber merchants and carpenters were thriving to rebuild.

Kinokuniya Bunzaemon was particularly famous at this time. He bribed Yanagisawa Yoshiyasu, a daimyo (feudal lord) of the Edo shogunate, and other top officials, and earned huge profits from the construction of the Konpon-chudo Hall of Kan-eiji Temple in Ueno, becoming a lumber merchant under the shogunate's warrant. However, Bunzaemon, too, lost his "Kinokuniya Lumber Shop" in a fire at Fukagawa Kiba, and his lumber business was closed down.

In the early Edo period, lumber merchants gathered near Nihonbashi, forming a lumber riverbank, but the damage caused by the Meireki Fire of 1657 was so great that the shogunate planned a major remodeling of Edo, relocating shrines, temples, and daimyo's residences to the suburbs. As one of the measures, lumber dealers were forcibly relocated from Nihonbashi to Fukagawa, across the Sumida River, because lumber yards were considered to be a fire hazard.

In this map, the east side of Tomioka Hachiman Shrine at the bottom is still under development and is still a waterfront.

This is a map of Edo drawn in 1857. This is just the year Hiroshige passed away. If you look closely, you can see that the lumber yard of Kiba has already been formed. The town of Edo itself, centering on Edo Castle, is almost complete. However, even after the Meireki Fire, fires did not cease to burn in the town of Edo, and the lumber merchants and carpenters continued to prosper, with many fine houses apparently being built in the vicinity of Kiba. By the time Hiroshige painted his picture, 16 of the 18 or so lumber wholesalers were concentrated in Fukagawa.

Along with the lumber merchants, these carpenters, who were well paid, received about 17 grams of silver per day, or 17,500 yen in today's terms. If the actual working days were 290 days, the annual income would be about 5.2 million yen. The average monthly rent for a tenement house in the Edo period is said to have averaged 500 mon about 7,500 yen in today's money, which means that people were able to live quite wealthy.

Although opinions differ depending on what standards are used to compare the price of rice and other items with today's values, it is said that carpenters earned more than 12 million yen a year in today's terms, and it seems certain that carpentry was considered one of the "marriageable professions" in the male-dominated "Edo town" of Tokyo.

As shown in this painting, most carpenters had carvings on their bodies and wore large topknots on their heads, and were synonymous with the chic Edo man who "never carried money beyond the night.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

Two sparrows are descending from the snowy landscape. In the center of the snowy sky, black clouds, printed with the "atenashi bokashi" technique, also give a wintery effect. On the far left, a slightly longer piece of lumber stands straight up.

The straight timbers, which are waiting to be shipped, are placed at an angle and protrude diagonally from both sides, creating a sense of perspective.

A moat for lumber storage has been dug in all directions in this area, and a large bridge crosses over it at the far end. On both banks of the river are the mansions of lumber merchants, who must have built them with their vast wealth. In the blue moat in the center, many timbers are floating, and above them are two men in straw hats, called "kawanami-tobi, who are experts in freely manipulating the timbers.

"Kawanami-tobi" in Kiba used to have a tattoo called "Fukagawa-bori" on their backs to distinguish their identity in case of drowning, as they were often involved in water-related accidents.

In the lower left of the painting, two puppies are depicted playing in the snow, and in the middle of the parasol, someone is passing by, watching the work of "Kawanami-tobi. The word "fish" on this parasol is said to represent the publisher "Uoei," but whether this was a pun or a gratuity, the true meaning of the word is now unknown.

On a quiet note, please take a look at Kawase Hasui's subsequent depiction of Kiba.

It seems as if Kawase painted Kiba with the same feeling as Hiroshige, doesn't it?

Now, I actually went to this place, but since the actual location is not known, I tried to capture the most plausible place with my camera.

The moat around Kiba has been converted into a water park. Part of the lumberyard has been transformed into Kiba Park and the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo.

See the aerial view looking west from the east. It is now impossible to discern which was the lumberyard except for Kiba Park.

Also see the aerial view from above Kiba looking toward Tokyo Bay. At the time of Ieyasu, the area you are looking at was mostly sea or marshland, except for the lower third of Tsukuda Island on the far right. What about now? Kiba itself was moved further to the sea side and is now called Shin-Kiba.

I tried to fit the present image into Hiroshige's painting.

The quiet atmosphere is similar to that of Hiroshige's painting, but it is even a bit lonely.

In the early Keicho period (1596-1614), when Edo began its town development, Fukagawa Hachiroemon, who came from Settsu Province (present-day Osaka), began to develop the area around here. Later, when Hiroshige painted this area, lumber merchants moved in from Nihonbashi, and the area became a lumber town.

After the Meiji Restoration, the offshore land reclamation proceeded, Kiba became inland, and the sea disappeared rapidly. In March 1945, the area was completely burnt to the ground in an air raid on Tokyo. In 1969, a new lumberyard, Shin-Kiba, was constructed on reclaimed land offshore, and the existing lumberyard was reclaimed and turned into Kiba Park. The moat that ran the length and breadth of the park was generally turned into water parks and walking paths, with condominiums and other buildings lining the sides.

In 1878, this area became Fukagawa Ward. In 1947, Fukagawa Ward was combined with Joto Ward to form Koto Ward. Therefore, the area that is now known as Fukagawa is only a small part of the northern part of Monzennakacho.

In Hiroshige's time, the world was in a period of uncertainty, with the arrival of never-before-seen black ships from the United States in Edo Bay and a flurry of sharp opinions about the Emperor of Japan and exclusion of barbarians. Looking at this painting again, I feel as if I can hear the disturbing footsteps of the era that continues to the present day, even in this seemingly peaceful and tranquil scene.

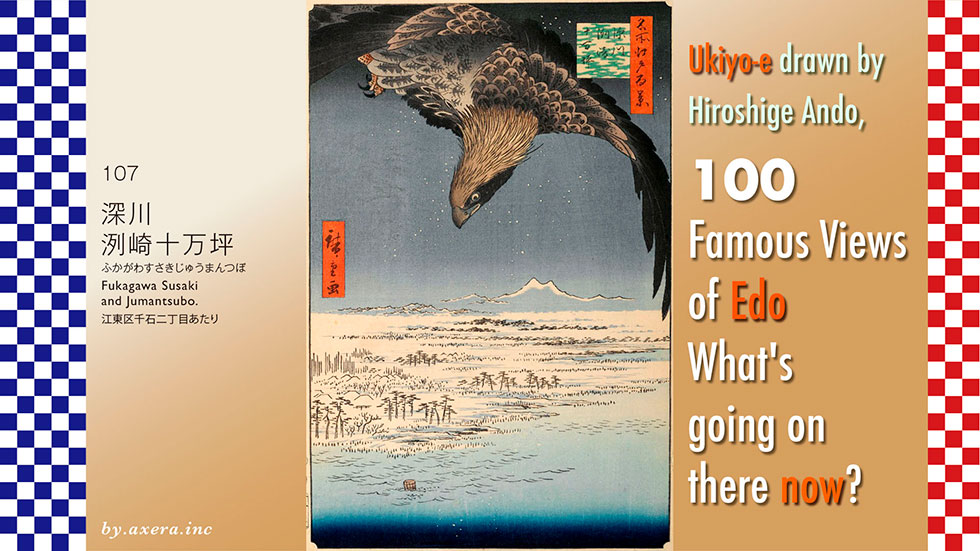

I visited the actual location of my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scene looks like today.

It is not known exactly from where he painted the 107 "Fukagawa Susaki and Jumantsubo". This is because Hiroshige's point of view was probably the sea at that time. However, he called the area on the north side of Kasai-bashi-dori, which is now Yotsume-dori, "Jumantsubo" as the title suggests.

Please check that location on the map first.

The area is about 7 km east-southeast of Edo Castle. The area called "Jumantsubo" is roughly surrounded by a red dotted line.

Let's zoom in on the map a bit and try to identify the place that was called that "Jumantsubo. Let's cover this map with a pictorial map of the time. The place surrounded by this red dashed line seems to be "Jumantsubo.

In the early Edo period, Hachiroemon Fukagawa, who came from Osaka by order of Ieyasu Tokugawa, reclaimed and developed this area, and after the great fire of Mereki in 1657, the development of the area began in earnest as the residences of feudal lords, shrines and temples were moved to Fukagawa.

From 1723, it was planned to reclaim the garbage generated in the city of Edo and turn this area of "Jumantsubo" into a new rice field. However, due to drainage problems, this did not work out, and although it was used as a coin foundry for a time, it was later taken over by the Hitotsubashi family and called "Hitotsubashi Jumantsubo.

The map also shows the name of a daimyo's mansion on the south side, but as shown in Hiroshige's drawing, the area was actually a tidal flat overgrown with reeds.

If this dashed line is put back on the current map and adjusted for differences in scale, etc., it is likely that the "Jumantsubo" was this red area.

Now let's actually take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

First of all, the highlight of the painting is the eagle that is covered from the snowy sky at night, which is depicted with a great deal of power. This is the only painting in this series by Hiroshige that depicts it so realistically.

Below it, Mt. Tsukuba, snow-capped in the distance, is highlighted. The puddle-like area to the right of center appears to be a pond where the Sendaihori River meets the Yokojuken River. To the left of the pond, the timber stands like a lumber yard Kiba and the roofs of its inhabitants.

The fact that the surface of the water is surging at the bottom of the painting indicates that the sea is quite shallow in this area. When the tide recedes, the entire area becomes a tidal flat. Pine trees are planted at the water's edge, and beyond that, reeds are painted in fine detail quite far back in the painting.

What is interesting is that a single wooden tub is depicted on the left side of the water. It is said that this may be a coffin of the time, called a "haya-oke," judging from its size, but why it is depicted here is a mystery.

I have actually been to this place. Rather than Hiroshige's point of view, the center of a place called "Jumantsubo" is probably this area. On the left is Hotel East 21, and the bridge in the foreground is the first bridge where the Yokojuken River turns west.

The hotel on the left was a piece of land owned by Hosokawa Echu-no-kami of Kumamoto during Hiroshige's reign. After the Meiji Restoration, the land was turned into a military facility, and then was sold to Kajima Corporation and used as a materials yard, where it was transformed into a hotel and commercial facility.

This is the view from the same location looking toward Toyocho Station, i.e., toward the sea. The Koto Ward Office is now immediately to the left.

This is a photo looking west from the bridge over the Yokojumen River on Yotsume-dori. East 21 is on the right. Kiba Park is at the back.

This is the street view from Applemap of this area. At the far end, you can see the current Arakawa River.

I tried to fit the present image into Hiroshige's painting.

However, the angle is a little different, so I inserted a processed image.

I believe that this painting may have depicted the view of life and death in Hiroshige's mind.

In fact, on the left side of the painting was the famous scenic spot, Susaki Benten Shrine. From here, one can see Edo Bay from the Boso Peninsula to the east to Shibaura to the west, and the area was very crowded with people who went out to enjoy the ebb tide in summer, moon viewing in autumn, and sunrise on the first day of the year on New Year's Day. If it were an Edo landmark, Susaki Benten Shrine would have been depicted.

The tidal range of Tokyo Bay is still about 1.8 meters. This vast sea with its tidal flats was a very rich sea and a very good environment for birds as well as fish. Migratory birds such as snipes and plovers from Russia and Mongolia probably flocked to the area every year. Nowadays, it would be a candidate site for the Ramsar Convention.

Hiroshige depicted such a place with overwhelming power, as if it were a landscape symbolic of the Latter Day Sect of Buddhism.

Mt. Tsukuba has long been revered as the male and female deities from its two peaks, visible even from Edo. In the tidal winter sea, where such a snow-covered mountain of conjugal harmony can be seen, a single coffin is now drifting out to sea. Inside the coffin is probably Hiroshige's own corpse, clutching his knees.

If you look closely, you can see that small fish are gathering there, and waterfowl are also coming to take advantage of them. An eagle, a bird of prey that stands at the top of the ecosystem, is aiming for it and looms large over it from above. It is as if the whole life of a person is expressed in this single painting.

Did Hiroshige think that once he died, he too would return to nature in this way?

Almost a year after this painting was published, Hiroshige was indeed reduced to a corpse by cholera.

About 10 years later, the Edo shogunate also became "dead" and a coup d'etat by Satcho succeeded.

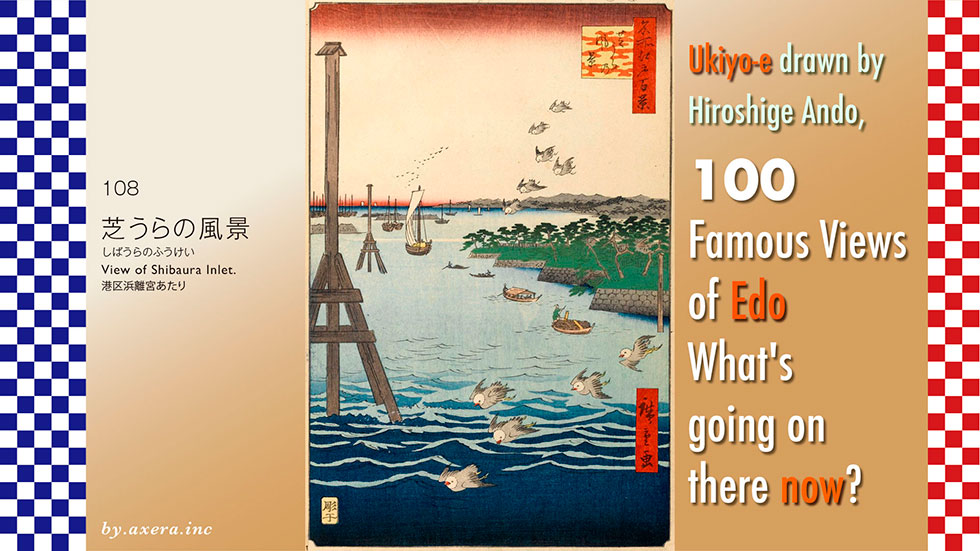

I visited the place where my favorite artist Hiroshige Ando painted "One hundred Famous Views of Edo" to see what the scene looks like today.

The 108 "View of Shibaura Inlet" is a view looking south from the east side of the present Hamarikyu, which was then the sea.

First of all, please check the map to see where this area called Shibaura was located at that time. It roughly refers to the sea on the Minato Ward side of Tokyo Bay. This area, where the Musashino Plateau falls to the sea, was called "Shiba" because grass grew over a fairly large area, and the land side was called "Shibahama" and the sea side "Shibaura".

Let me cover this with a relatively accurate map from 1881. You can clearly see that even at this time, this area was the sea.

During the Edo period, what is now Shimbashi was called Shibaguchi (Entrance of Shiba), and Tamachi was called Motoshiba (Original Shiba). Even before Tokugawa Ieyasu arrived in Kanto in Tensho 18 (1590), there were numerous fishing villages in Edo Bay. The sea at the mouth of the Furukawa River was a particularly famous fishing ground, where shellfish, eels, shiba shrimp, flounder, and black sea bream were caught, and there was a fish market called Zakoba. It was also one of the "Osaisakana Hachigaura," where special privileges were obtained by offering fresh fish and other products to the Shogun's family.

One of the famous rakugo stories, "Shibahama," is also set in this area.

It is a story about a down-on-his-luck fisherman who picks up a wallet containing a large sum of money on the beach on his way to the fish market in Shiba.

Let's enlarge the map a little more and put a red gradient on the place where Hiroshige's point of view would have been.

Then, I cover it with a map published in the year Hiroshige painted this picture. You can see that at that time, the current Hamarikyu was the residence of the Hama Palace and the current Shibarikyu was the residence of the Kii Palace.

Let me cover this with a more accurate scale map from 1881. You can see that by this time, the residence of the Kii Palace had become Shiba-Rikyu.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting. First of all, the white-headed bird flying in the sky is a winter-feathered Black-headed Gull. It is said to be the bird called "Miyako-dori" by Ariwara no Narihira in Ise Monogatari (The Tale of Ise).

The mountain in the distance is Yatsuyama, to the left of which is Shinagawa-juku, to the right of which is Takanawa, and further to the right is the fishing village of Shibaura, which leads to the mouth of the Furukawa River at the far right.

Here is the map again from 1881. I painted Hamarikyu Garden in blue and added Hiroshige's viewpoint in red gradient.

Shibaura, with its large arc-shaped stretch of sandy beach, was also famous for its moon. The fish caught here were so tasty that they were called "shiba sabana". As time went by, it was called "Edomae," meaning that the fish was caught in front of Edo, and it became even more highly prized.

In the distant left view, you can see what looks like several platforms along with boats with sails, which are platforms. These are gun emplacements built by the Edo Shogunate in a panic as a defensive measure in Edo Bay in response to the surprise of the black ships from U.S.A.

The island-like stone wall with pine trees on the right is said to be the Hamarikyu Gardens, which still remain today. However, when examined, the stone wall of the Hama Palace at that time is straight.

Here is a capture by Tokyo History Map2. I added Hiroshige's point of view to this.

This shows that the stone wall on the right side of the painting was not only Hamarikyu Gardens but also a series of daimyo's residences.

On the far right is the Hama Palace, on the left is the residence of the Kii family of the Wakayama domain, on the left is the residence of the Niwa family of the Mutsu Nihonmatsu domain, and on the far left is the warehouse residence of the Matsudaira family of the Aizu domain.

It seems that Hiroshige deformed them well and made them look continuous.

Today, from right to left, the Hamarikyu Gardens, Shiba Rikyu, Tokyo Gas headquarters, Toshiba headquarters across the Furukawa River, and the Sea Vance.

The area around the stone wall and pine trees on the right side of Hiroshige's painting was a marshy area with thick reeds that served as a hunting ground for the shoguns until around the end of the Kan'ei Era (1644). The area was reclaimed with soil from the excavation of the Kanda Waterworks and the present Kanda River, and Tsunashige, the younger brother of the fourth Shogun Tsunayoshi, built a villa here. When his son Ienobu became the 6th Shogun and moved to Edo Castle, this area came to be called the Hama Palace.

Two large stakes are depicted on the left side, which were called "otome-gui," a kind of boundary to indicate that from here the land belonged to the Shogun's family. There were a total of four of these stakes around the Hama Palace. However, for fishermen and boatmen, these piles served as "miotsukushi" for boats navigating in this area, as they were able to observe the difference between the ebb and flow of the tide.

Hiroshige also depicted this area in his "Picture Book Edo Souvenir", in which this "otome-gui," is also depicted as a symbol of Shibaura.

In his "Picture Book Edo Souvenir," Hiroshige also painted another picture looking at Zojoji Temple and Shinmei-gu Shrine from the sea. The sea in this area was quite busy with various boats.

This is a painting by Hiroshige depicting the direction of Edo Castle from the sea in Shibaura. You can see that there were quite a few fishing villages in the town of Shiba.

This is a picture looking toward Takanawa from the mouth of the Furukawa River. You can see that when the tide receded, the beach was quite far offshore.

This is a view from Mt. Atago toward Shibaura and the mouth of the Sumida River. There are many fire watchtowers near Toranomon in the foreground, indicating that there were many samurai residences.

I actually visited this location. Currently, a new Loop Route 2 has opened on the south side of the old Tsukiji fish Market, and a bridge called Tsukiji Ohashi has been built. This photo was taken from that area.

The stone-walled garden on the right is the Hamarikyu Gardens, which used to be the shogunate's the Hama Palace and is now a metropolitan park.

In front is what used to be the sea, but is now lined with hotels, business buildings, and theaters, thanks to the redevelopment of Takeshiba Pier and the surrounding area.

After Hama-rikyu garden is the reduced Shiba-rikyu, but it is not visible in the shadows of trees.

If you swing your viewpoint to the right, you can see a full view of the Hamarikyu Gardens. With an area of 25 hectares, it is one of the largest remaining daimyo's gardens in Tokyo. Next to the garden is a pier where visitors can board a water bus to Asakusa, making it a famous sightseeing spot in Tokyo.

To the right behind is the redevelopment area of Shiodome, with its forest of high-rise buildings.

If you turn your viewpoint to the left, you can see beyond the weir of the Sumida River in the foreground to the Kachidoki and Toyomi areas, with the Rainbow Bridge on the far right side. The left side of the photo was the sea at the time of Hiroshige, and the south side of Tsukuda Island at the mouth of the Sumida River was progressively reclaimed and made into land up to this point.

This is a photo of Hiroshige's viewpoint from the south. The vacant lot in the front is the redevelopment area of the former Tsukiji fish Market, the Hamarikyu Gardens are on the left, and the Sumida River is on the right.

This is an aerial view of Hamarikyu Gardens from the north. You can see that the beautifully lapped sandy beach and the sea, which used to be a rich fishing ground, have been filled with buildings.

I decided to be playful and fill in the area that would have been the sea at that time with seawater. You can see the amazing desire for human development.

I embedded the current photo in Hiroshige's painting. The view that could be seen as far as Shinagawa is blocked by many buildings. Except for the water surface and the Hamarikyu Gardens there is no trace of those days.

This painting by Hiroshige was one of the first five released in the "One Hundred Famous Views of Edo" series in February 1856.

In 1853, the shogunate was surprised by the appearance of black ships off the coast of Uraga and hurriedly built a platform to serve as a gun emplacement in Edo Bay, but in November 1855, a major earthquake hit Edo, causing the middle platform depicted in the painting to largely collapse. However, Hiroshige painted it as if all the platforms were intact.

The large "otome-gui," in the painting strongly indicates that the Hama Palace was the departure point for the Edo Castle of the Tokugawa Shogunate and that no one was to enter beyond this point.

Matsudaira Katamori of the Aizu domain, the owner of a warehouse surrounded by stone walls at the far end of the castle, was treated as a dynastic enemy after he and Tokugawa Yoshinobu and others launched the Battle of Toba-Fushimi in the first month of 1868. He then returned to Aizu Castle and fought a thorough war, but surrendered to the allied to the government forces in September of the first year of the Meiji Era (1868).

While the winds of such an era are blowing strongly, the city birds are soaring happily on the headwind. The migratory Black-headed Gull are leaving for the next new country by the time their heads turn black.

This small painting seems to depict many storytellers of such an era.

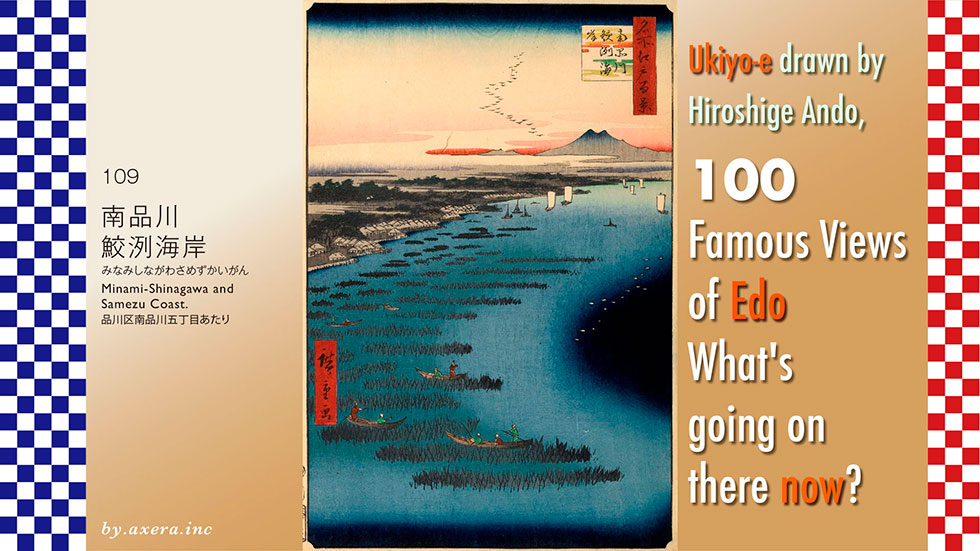

I visited the actual location of my favorite "One hundred Famous Views of Edo" painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scene looks like today.

It is said that "Minami-Shinagawa and Samezu Coast" (109) is a bird's-eye view from the beach east of the current Keikyu Tachiaigawa Station toward Samezu Station, but the exact location is not known.

First of all, please check the map to see where the coast of Samezu was located.

The map shows that the area has been eroded by reclaimed land, and is not really a beach. The area is roughly south of Shinagawa Station, roughly enclosed by a red dotted line.

Looking at the enlarged map, it appears to be from the north side of Keikyu's Aomono-Yokocho station to the north side of the Tachiaigawa area. Here, too, the area is circled by a red dashed line. However, the area is mostly reclaimed land rather than coastline, and the Katsushima Canal barely remains to the east of Tachiaigawa Station, leaving the waterfront. Furthermore, although Samezu Station and Samezu Driver's License Examination Center are currently located in the area, neither Samezu nor Samezu Kaigan addresses exist in this neighborhood.

At that time, this area was outside of Edo, so there are no pictorial maps of the area. Therefore, please see the map of the GSI (Geospatial Information Authority of Japan), which shows a slightly wider area, with a red dotted line in the area that appears to be Samezu Beach, and a map of the same scale dated 1881.

The area formerly known as Samezu Beach has been reclaimed and Kaigan Dori runs north-south parallel to Daiichi Keihin Road. To the east, two expressways, the Keihin Canal, Yashio Danchi and the Shinkansen rail yard, and Oi Wharf spread out widely.

In the map of 1881, the reclaimed land is completely gone, and the old Tokaido way can be seen running along the coastline. The slightly thinning area along the coastline is an area that becomes tidal flats due to the ebb and flow of the tide. Many seaweed cracks have been set up in this area.

Hiroshige depicted Samezu in a similar composition in his picture book Edo Souvenir.

Originally, Asakusa was famous for its seaweed, and by 1457, "Asakusa's seaweed" was well established. However, until the middle of the Edo period, people ate laver made by a method called ten-en-ho, in which the laver was spread and dried as it flowed down the river. According to the book, nori hibi began to be used around the Genroku period (1666), when seaweed was grown on brush that was erected in the sea and the seaweed was collected.

Later, a method was established to turn the collected seaweed into dried laver boards, and "Asakusa Nori" became famous throughout Japan. However, in 1685, Tsunayoshi Tokugawa, the fifth shogun of the Edo shogunate, issued a prohibition against fishing in the Asakusa area in 1692.

In response, Asakusa fishermen abandoned their hometowns and moved to Omori, south of Edo, where there was a river where they could moor their boats. There, the famous Asakusa nori was relocated to the Omori, Shinagawa, and Samezu coastal areas, but the name "Asakusa nori" spread throughout in Japan. Today, Saga, Fukuoka, and Kumamoto prefectures facing the Ariake Sea are among the five best producers of the seaweed.

Let us take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

First, Mt. Tsukuba is visible beyond the flying geese, and the Nikko mountain range is depicted in a smaller size to its left. Edo Bay appears below the hazy clouds, and Shinagawa is the first village on the left of the cape. Many large sailing boats are depicted in Edo Bay.

A little below the Shinagawa Shuku is Kaienji Temple, from which the name Samezu Beach is derived.

In 1251, a wooden statue of the Holy Kannon (Goddess of Mercy) was found in the belly of a large whale that had been launched into the Shinagawa Sea. When the statue was reported to the Kamakura Shogunate, Hojo Tokiyori ordered the temple to be built and enshrined, and thus Kaienji Temple was established. From such an origin, this area was called Samezu(same=whale).

Nori hibi are drawn like branches in the sea. Around the time of the autumnal equinox, fishermen go around the sea to place branches of trees in the sea, which are called "Soda. After the autumnal equinox, the branches begin to grow and the laver begins to attach itself to the branches. Fishermen get up early in the morning, go around the branches, pick up the laver, chop it finely, strain it, and dry it on the bamboo screen. This process of making dried laver was a winter tradition in this area.

I actually went to this location.

This is the view from the south side of Katsushima Canal looking toward Samezu Station. Kaienji Temple is on the left, well beyond this picture.

This photo was taken from the canal edge beside the Metropolitan Expressway No. 1.

This is a photo taken from the edge of the canal on the old Tokaido side, a little closer to Samezu Station.

I tried to fit the current photo into Hiroshige's painting.

Tsukuba should be visible from this direction, but the height of the viewpoint is not high enough.

So, we combined Street View from Applemap and Google Earth to recreate Hiroshige's point of view. What do you think? The changes are so drastic that you can't help but look at them.

Fishermen who moved from Asakusa during the Genroku period came to Samezu in search of a river where they could moor their boats and a sea with brackish water and mud flats. Today, the coastline has been pushed far away, and only a few canals remain, which are the only remnants of the sea.

Recently, Tokyo Bay has become much cleaner from the dirty sea it once was. Perhaps as a result of this, we can now see what looks like seaweed adhering to the mooring ropes of boats moored in the Katsushima Canal in winter. Human destructive development may be one of the teeth in a big wheel for nature.

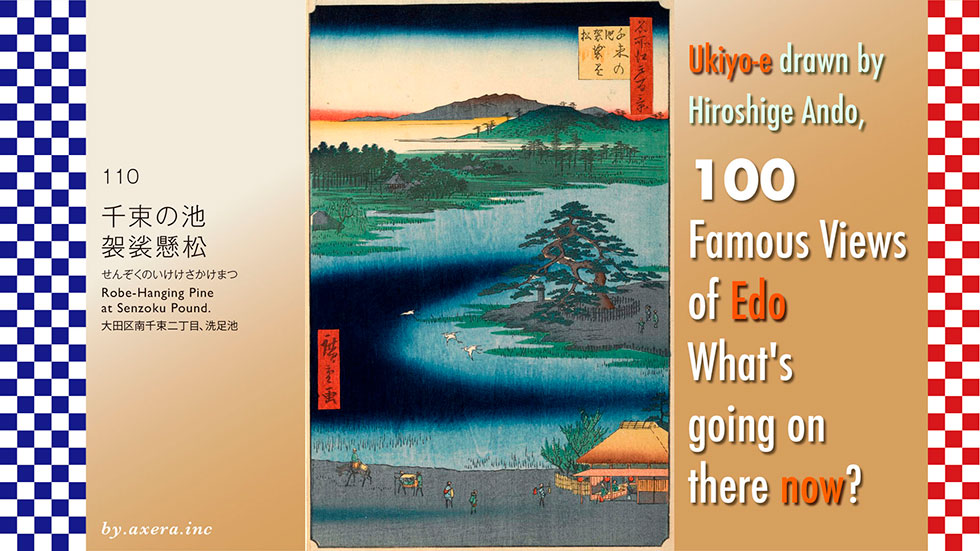

I visited the actual location of my favourite painting, One hundred Famous Views of Edo by Ando Hiroshige, to see what the scene looks like today.

110, Robe-Hanging Pine at Senzoku Pound, depicts the pond north of Senzoku-ike Station on the present-day Tokyu Ikegami Line, from the south. The stunning pine tree by the pond was a scenic spot where Nichiren is said to have taken off his kesa (priest's robe) and hung it up to wash his feet.

First see where this location is on the larger map. If you follow the present-day Haneda Airport to the west-north-west, you will find a small pond. That pond is the setting for this story.

See an enlarged map of this area. To the south of the pond is Senzokuike Station, and the road between the station and Senzokuike Pond is Nakahara Kaido, which forms a large slope back and forth with the bottom of a mortar around Senzokuike.

Hiroshige's viewpoint is from around the police station, which is now located on the east side of this pond, looking north-west.

This Nakahara Kaido is a road that has been in use for quite some time, crossing the Tama River at Maruko from Toranomon and running almost straight through to Nakahara in Hiratsuka. It is said that Ieyasu Tokugawa took this road when he came to Edo. Even after the Tokaido Highway was built, it was actively used as a side road to the Tokaido Highway.

There were no pictorial maps of this area outside Edo at the time, so please refer to the Rekichizu. You can see that the Nakahara Road extends from the lower left to the upper right towards Edo. Nichiren rode his horse around the north of Mt Fuji, and from Hakone, followed the Nakahara Road to reach Senzokuike Pond. Southeast of here is Ikegami Honmonji Temple, which is believed to be the place of his death.

Hiroshige depicted the same place in the same composition in his picture book Edo souvenirs. This Senzoku Pond was formed when spring water from the Musashino Plateau was stored in a depression and was used for irrigation for a long time. It is estimated that it was considerably larger than today's ponds.

Nichiren is said to have been born in Awa Kamogawa in 1222. In order to examine the doctrines of various sects, he studied at Enryaku-ji Temple on Mount Hiei, Koyasan and elsewhere, and in 1260 he submitted his "Rissho Ankoku Ron" to the highest authority of the time, Hojo Tokiyori, the fifth regent of the Kamakura shogunate.

The Rissho Ankoku Ron condemned other sects for bringing about the end of the world and urged them to use the Myoho-renge-kyo Sutra to lead the country and people in the direction of peace and security.

The following year, however, Nichiren was detained by the Shogunate and exiled to Ito in Izu. After that, Nichiren repeatedly proposed his theory to the Shogunate, but it was not accepted, and in 1274 he left Kamakura and went to Minobu in Kai Province, as he thought further activities were pointless.

In May 1281,a Mongolian army headed for Japan, but in July they were hit by a large typhoon and retreated with devastating damage. The Mongol invasion was a good opportunity to prove the correctness of Nichiren's Latter-Day Buddhist philosophy and his prediction of a foreign invasion, but as a result, the Mongols were victorious thanks to the prayers of the Shingon priests, who had condemned the sect as evil.

Meanwhile, Nichiren had been suffering from gastrointestinal illness since the end of 1277, and after the failure of the Mongol invasion, he deteriorated until he became aware that his death was imminent. In the autumn of 1282, his illness progressed further, and his followers, seeing that it would be impossible for him to survive beyond the New Year in the cold of Minobu, discussed the matter and decided to have him recuperate in the hot springs of Hitachi before winter set in.

Nichiren left Minobu on horseback on 8 September and arrived at Ikegami Munenaka's mansion in Ebara-gun, Musashi Province, ten days later, but he was too weak to travel any further.

In this condition, it seems doubtful that Nichiren stopped at Senzoku Pond, took off his robe, hung it over a pine tree and purified his feet.

On 13 October, Nichiren gave his last lecture on "Rissho Ankoku-ron" to his students, who had gathered from Kamakura, Fuji, Shimousa and other places after learning that Nichiren was staying at the Ikegami residence.

After his death, Ikegami Munenaka built Choeizan Honmonji Temple on the mountain behind the pavilion as a memorial to Nichiren. Afterwards, Nichiren's disciple Nichiro succeeded to this Honmonji, which continues as Ikegami Honmonji today.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

The grey colour at the bottom is the Nakahara Kaido, the Nakahara Road at the time. Travellers of various styles, palanquins and horses are also depicted, alongside a teahouse and even two travellers and the owner relaxing inside.

Three egrets fly above the pond, and to the right of them, surrounded by stakes, is the pine tree with the wavy branches of the Kesa Kakematsu (Robe-Hanging Pine). If you look closely, you can see three tourists are also depicted here. The stone pillar to the left of the pine tree is a nameplate with information on its origin, built in the Tenpo era.

The building with the torii gate in front of it on the far left of the pond is the Senzoku Hachiman Shrine, which is the god of war and was dispatched from Usa Hachiman in Oita. It is also known as Hataage Hachiman, as Minamoto no Yoritomo set up camp here after his defeat in the Battle of Awa, before returning to Kamakura.

The green mountain to the far right may be the rising Ookayama or an exaggerated depiction of Setagaya Castle further ahead. The mountain behind it is the Chichibu mountain range in the direction.

I have actually been here.

This is the view of the pond from Senzokuike Station over Nakahara-kaido Road. The shore of the pond also seems to serve as the station's bicycle storage area.

This is a view looking slightly to the right as you reach the edge of the pond. The Robe-Hanging Pine tree is hidden amongst these thick trees. Behind it is the hall of Shichimen Daimyojin, who is said to have subdued a giant snake that lived in the pond.

If you look slightly to the left, you will see a private house, behind which is Senzoku Hachimangu Shrine. This is the shrine on the left side of Hiroshige's painting.

This is an aerial view of Senzoku Pond from the east. The green line running left and right is the Tama River, and the high-rise buildings on the left are around Kosugi. The Nakahara Kaido extends all the way to the end of the river. At the far right, beyond the Tanzawa Mountain Range, you can see Mt Fuji. To the far right of this Mt Fuji is Mt Shichimen and Mt Minobu.

I added Hiroshige's viewpoint to this in a yellow gradient.

The current image is inset into Hiroshige's painting. I used a high angle, Google Earth image. It seems that the mountains were not actually visible from the shore of the pond on this hollow piece of land, as the Chichibu mountain range is visible all the way across.

The name Senzoku is said to derive from the fact that the residents of the area were originally exempted from the tax on rice senzoku (1,000 bunches) because this pond was the source of water. As Nichiren's legends became famous, the name of the pond was changed to Senzoku, which means "feet to wash". That is how much influence Nichiren had on the world.

Every year, around 13 October, the day of Nichiren's death, many believers from all over the country would gather at Ikegami Honmonji for the 'Oeshiki' ceremony, where they would parade through the town in procession, waving Mantō and Matoi, and rhythmically ringing bells and fan drums. This Manto-Kuyo is still a major seasonal event in Honmonji, with a total of 3,000 people parading through the town until late at night, attracting more than 300,000 spectators.

Here, you can also see Kawase Hasui's painting of the serene Honmonji Temple and Senzoku Pond.

I have just realised that perhaps the mountains in the back of Hiroshige's painting are not the Chichibu mountain range, but rather Mt Shichimen or Mt Minobu, which he may have intended to depict.