I visited the actual location of my favourite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scene looks like today.

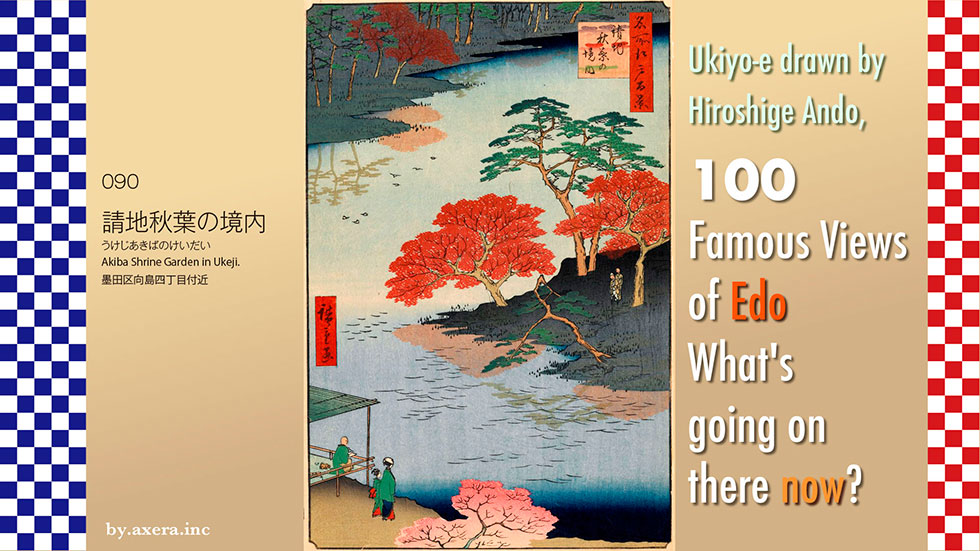

091, 'Akiba Shrine Garden in Ukeji', depicts the garden in the precincts of Akiba Shrine, which was located around the current Mukojima area.

First, please use Applemap to see where this location was. It's about 6 km northeast of Edo Castle, just across the Sumida River from Sensoji Temple.

As you can see if you zoom in on the map a little more, it is just to the west of Hikifune station, over the Mito Kaido road.

This is a capture of the Oedo Konjaku Meguri app on the iPad. The shrine symbol in the middle is the current location of the Akiba Shrine. I put a map of the time on top of it. The pink colour shows how large the grounds of this shrine were.

Furthermore, superimpose this site on the current aerial photograph. You can see that it was about the same size as the Keisei and Tobu Hikifune Station redevelopment area on the right.

Furthermore, as seen in the Tokyo Historical MAP2, its size is comparable to the current site of Senso-ji Temple. You can also see that it is larger than the Solamachi complex, which spans Tokyo Skytree Station and Oshiage Station to the south of it.

Let's take a closer look at the actual painting by Hiroshige. The Akiba Shrine in this contracted area was visited by many people in Edo at that time as a famous place for autumn leaves. You can see its autumn leaves depicted everywhere.

The pond bends to the right, as seen on the map, and the autumn leaves and blue pine trees reflected in the water are also painted in different colours. What appears to be a metropolitan bird flits about the water's edge, and on the island to the right, an elderly couple in a retired life-style are depicted as travellers.

In the bottom left-hand corner, there are two autumn leaf peepers, one of whom appears to be a geisha from Mukojima, and the other who is picking up a paintbrush at a teahouse. The shaven-haired man in the teahouse is said to be Hiroshige himself.

See a map showing the current elevation difference here. Originally, this northern side of Tokyo Bay was a vast flood plain where two major rivers, the Tone and Arakawa, flowed in from upstream. This is the area that has turned from green to blue. Nevertheless, each time that flooding occurred, the sediments that flowed from upstream gradually deposited and formed slightly higher areas.

A map of the lowlands of Sumida Ward shows that the area west of Hikifune and around Mukojima is slightly higher, where the deposits are stored, coloured in yellow. When looking at this from the Asakusa direction, it seems to have been called an island or floating island across the river. It seems that this floating island became 'ukichi' from ukiji, which became "Ukeji" and became a common place name.

Eventually, this slightly higher area became overgrown with vegetation and trees, including pine trees. The whole area around here was called Iozaki, and the woodland area was called "Chiyose no Mori, where a small Inari shrine was enshrined. This Edo Meisho Zue is a detailed depiction by Hasegawa Settan of this area afterwards.

In December 1702, Chibashoei Chiba founded Shugendo's Chibayama Manganji, which became a separate temple, i.e. the temple in charge of the Inari shrine, and painstakingly rebuilt Chiyose Inari, which in the past had been little more than a small shrine, into a larger temple. Later, Akiba Gongen, the god of fire prevention in Shizuoka, was offered to the temple, providing emotional support for the people of Edo, where fires were frequent.

The area around Manganji Temple became famous for its forest fountain with ponds and trees, and for the many autumn leaves that were planted. The temple was also worshipped by feudal lords and their wives as a god of fire protection, and many lanterns still remain in the precincts of the temple.

The current electric town of Akihabara derives from "Akibappara, a fire protection area where Akiba Shrine is located.

Because it attracted so many people, there were three restaurants in the precinct that became very famous. These restaurants specialised mainly in carp and river fish cuisine, and all three are depicted in Hiroshige's guide to restaurants in Edo. The first restaurant is Hiraishi, where a master is depicted guiding Mukojima geisha, led by a sycophant.

The second house is Musashiya, depicting Edo townspeople playing geisha while carp dishes are being served. Outside on the right, you can also see many ponds and donated lanterns!

The third house, Daishichi, is a place where the summer evening cools down, and townspeople and Mukojima geisha are chatting and laughing while wiping off their sweat. The restaurant on the other side of the pond is probably the ryotei Daishichi.

I actually went to this place. But there is no shrine with such a large garden anywhere. I managed to find the shrine building by going down a narrow alley surrounded by houses from the busy Mito Kaido Road.

More than ten years after Hiroshige painted this picture, in 1868, due to the new government's decree separating Shintoism and Buddhism, Manganji Temple, which was a separate temple, was abolished and its name was changed to Akiba Shrine. Later, the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 destroyed the shrine, and although it was temporarily reconstructed, it was destroyed by war during World War II.

According to the records, the company's land must have been nearly 7,000 tsubo (about 23,000 square meters), but today it is less than 300 tsubo when I look around.

Furthermore, a four-lane Mito Kaido road like this one runs right through the middle of what was then the site.

The current state of the pond is shown in Hiroshige's painting. This is a street view of the area around Cherry Blossom Children's Park, where the pond would have been located at that time.

However, it is so far removed from the painting that I have inserted the area around the current shrine building. I was surprised to see how much things have changed in only 170 years since Hiroshige painted this picture.

According to an aerial photograph taken on April 2, 1945 by the U.S. Army in the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, the Great Tokyo Air Raid burned down the entire downtown area from the Akiba Shrine area to Fukagawa in the south. Ironically, it appears that even Akiba Daigongen, a deity specializing in fire protection, was no match for the bare human warfare.

The vast popular tourist attraction, burned to the ground by the U.S. military, has now lost its pond and foliage, and only the cozy shrine pavilion, guardian dogs, and lanterns stand quietly in the shade of the trees.

I visited the actual location to see what that scene looks like today in my favorite "Meisho Edo hyakkei" (One hundred Famous Views of Edo) painted by Hiroshige Ando.

I visited the actual location to see what that scene looks like today in my favorite "Meisho Edo hyakkei" (One hundred Famous Views of Edo) painted by Hiroshige Ando.

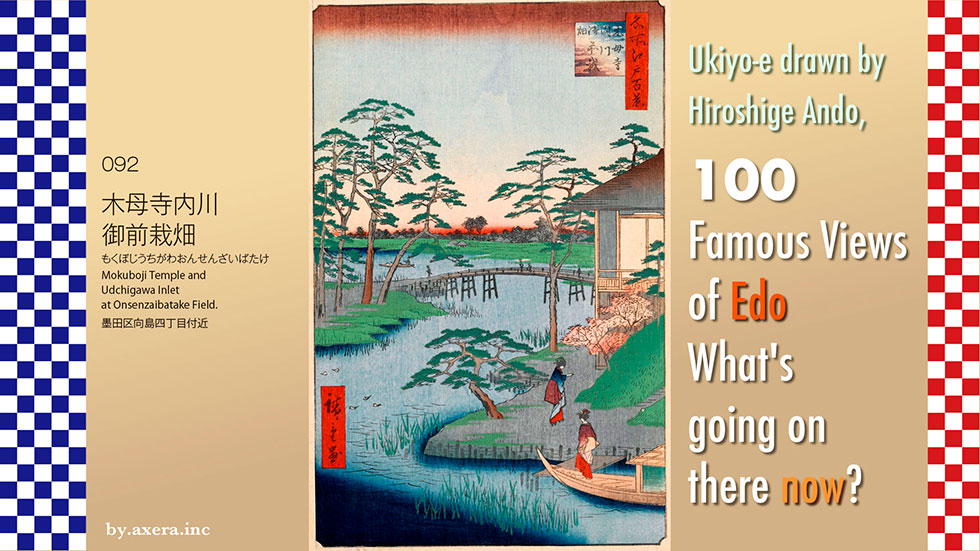

092, "Mokubo-ji Temple and Udchigawa Inlet at Onsenzaibatake Field," depicts a cove around a temple that was located in the area of today's Higashi Shirahige Park.

First, please check this location on the map. It is about twice as far northeast from the Edo Castle as Kan-eiji Temple in Ueno, where the Sumida River makes a big bend.

Please see a slightly enlarged map. This is the area where the Sumida River makes a big curve on the east side of Minami-Senju, south of the Suijin Ohashi Bridge, around Higashi Shirahige Park.

I superimposed an old map of the time on this one, but it is a bit confusing.

Please take a look at the captured screen of the iOS application "Edo Konjaku Meguri". I put a map of the period on top of it and added red gradations in the places that would have been from Hiroshige's point of view.

This area has long been a source of flooding, with the Arakawa and Tone Rivers flowing into the area, but by this time in Edo, the river flow was much improved. You can see the inlet of the Uchikawa entering on the right side from the Sumida River, which is marked as the Okawa. On the island that is like a sandbar, there was Mokubo-ji Temple.

If you overlay this with an aerial photograph, you can see that this whole area has been transformed into a large park and apartment complex.

In his picture book Edo Souvenir, Hiroshige painted a snowy scene of this location from almost the same angle, with commentary. However, although he depicted a side restaurant, he did not depict the Mokubo-ji Temple.

The same place is also depicted in Hiroshige's introduction to a famous Edo dinner party. This is a restaurant called Uehan, famous for its eight-head potato and shijimi clam dishes, and the scene where the master arrives with the Mukojima geisha and disembarks from the ship. Crossing the bridge at the back to the left is the Onsenzaibatake field, a field used exclusively for growing vegetables for the Shogun's family. Mokubo-ji Temple was located behind this ryotei.

Hiroshige also depicted the ryotei as seen from the opposite bridge side in his eight views of the Sumida River. Again, Mokubo-ji is not depicted, although it is mentioned in the title.

Katsushika Hokusai also painted this area under the title Snow, Moon and Flowers. Hokusai painted the Suijinja Shrine more to the west in the foreground, and both the ryokan and the Mokubo-ji Temple in the shadow of the mountain. The left side of this painting is the inlet of the Uchikawa.

Hiroshige left a painting with an explanation of the origin of this Mokubo-ji temple.

In the mid-Heian period, there was a noble couple, Yoshida Shosho Korefusa and Hana Gozen, in Kitashirakawa, Kyoto. When their son Umewakamaru was five years old, his father Korefusa died at a young age. At the recommendation of those around him, Umewakamaru was ordained at the age of 7 and sent to Enryakuji Temple on Mount Hiei. However, he was bullied by the children and priests around him for being too clever, and fled to the beach at Otsu. There, he is kidnapped by a man-buyer from Mutsu named Shinobutota and brought to the eastern part of Japan. The painting on the right depicts Shinobutota beating Umewakamaru with a stick.

Eventually, Umewakamaru fell ill and died at the young age of 12 on the banks of the Sumida River. A passing Tendai priest, Chuen Ajari, built a nembutsu-do (Buddhist prayer hall) to offer his condolences. On the other hand, Hanagozen's mother, who had come to the East to look for her son, broke down and cried like a mad woman when she heard that her son had died here on the very day of the first anniversary of his death. Hanagozen then built a hall beside the Nenbutsudo and began to live there, but she was unable to bear the overwhelming grief and Kagami threw herself into the pond. The painting on the left depicts Hanagozen wandering along the Sumida River in a boat.

Chuen Acharya, in turn, also built a graveyard for his mother and maintained Umewakamaru's Nenbutsudo as Umewakadera Temple. As time went on, this sad tale became the subject of noh, joruri, and kabuki performances, and was actively performed as "Sumidagawa monogatari" (Sumidagawa stories).

It is said that Mokubo-ji Temple was named after the Chinese character for ume , which is a radical of the old Chinese character for plum, by separating the kanji for ume and its radical.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

The distant view in this painting, with the Sumida River in the background, shows the appearance of Suda Village at that time. On the right side of the painting, Uehan Ryotei restaurant is depicted, and Mokubo-ji Temple was located behind it on the right. On the left side of the bridge is the Onsenzaibatake field of greens for the Tokugawa family.

The Uchikawa, an inlet of the Sumida River, is depicted with a oyster catcher, as read in a poem of resignation by Umewakamaru, and is surrounded by many pine trees, which were well received for their beautiful branches.

The landing area in front of the ryotei depicts a Mukojima geisha just disembarking from a boat, with a colored maple tree beyond.

I actually went to this location.

This is the area where the Mokubo-ji Temple and the inlet of the Uchikawa River were located.

Please see an aerial view of this neighborhood. This area was designated as the Koto District Disaster Prevention Center, and was developed and opened in June 1986 as Higashi Shirahige Park, equipped with various facilities for disasters. At that time, Mokubo-ji Temple was also moved from the yellow circle to its current location in the red circle.

As you can see in this photo, the adjacent Shirahige East Apartment Building (Shirahige Disaster Prevention Complex) also serves as a huge firewall separating the east and west sides of the park.

This is the current Mokubo-ji Temple, which has moved and become a bit more modern.

Immediately to the right as one enters the precincts of the temple are the Umewaka-do and Umewaka-zuka, which are surrounded by glass side by side.

I tried to fit the current appearance into Hiroshige's painting. I feel that Umewakamaru's time has passed far, far away.

This area was on the Oshu-kaido road to Tohoku and was a busy place for traffic from Kyoto.

Umewakamaru recalled a poem by Ariwara no Narihira from the Ise-Monogatari and read it as a phrase of resignation: "Tazunekite Towabakotaeyo Miyakodori Sumidagawara-no Tsuyuto kienuto, The story was "If someone comes to visit and asks you, tell them that I died in Sumida-gawara.

The original poem by Ariwara no Narihira reads, "Na-nishiowaba Iza kototown miyakodori waga tsumaha ariyanashiya" The story was "Miyako-dori(oyster catcher), since you have Miyako in your name, do you know how my girlfriend is doing now in Kyoto?

It is said that one year later, her mother, Hana Gozen, also visited this area and remembered a poem by Ariwara no Narihira, and replaced the lover in the poem with her own child, asking the bird a lot of questions.

The cove is now a quiet park bathed in the afternoon sun.

I found Umewaka's picture story show.

https://youtu.be/i_QSU0dS7UQ

I actually visited the place to see how the scene of my favorite "Meisho Edo hyakkei" (One hundred Famous Views of Edo), painted by Hiroshige Ando, looks like today.

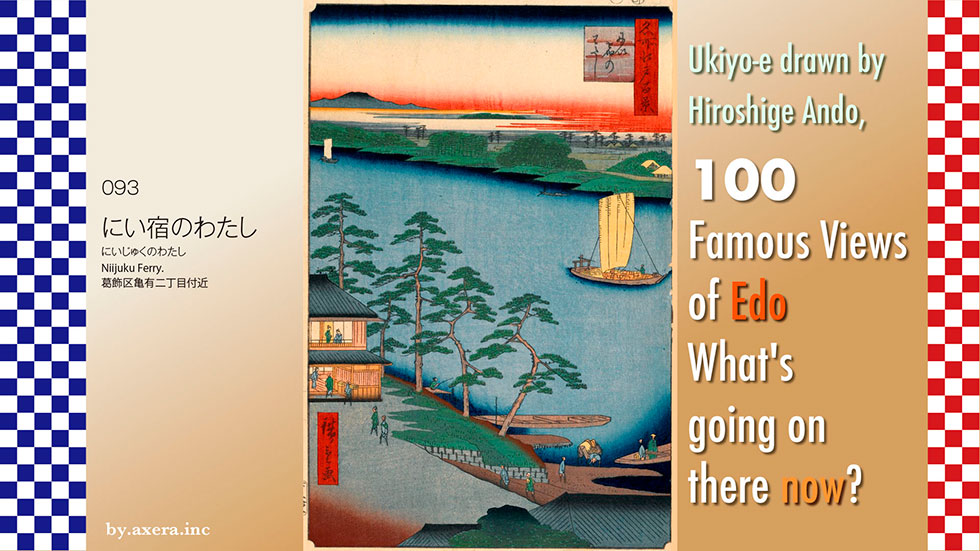

The "Niijuku Ferry" in 093 refers to a ferry located near Nakagawa-bashi bridge, east of the road on the south side of today's Ito-Yokado Kameari store.

Please check this location first.

Now, instead of the "Niijuku Ferry", the Nakagawa Bridge is helping the east-west traffic. Here is Hiroshige's point of view, the gradation. Actually, there are two theories that this painting was painted from the Kameari side and the Niijuku side. In the Kameari theory, the mountains in the back are the Nikko mountain range, while in the Niijuku theory, the mountains in the back are the Chichibu mountain range.

The Kameari theory is represented by a red gradation, while the Niijuku theory is represented by a green gradation.

Here I resorted to Google Earth. First of all, the picture of the Kameari theory looks like this. The Nikko mountain range is just barely visible, but Mt.Tsukuba. However, the angle of the river is a little too steep.

This is the Niijuku theory. If you match the angle of the river, the Chichibu mountain range is quite far to the right, and Mt. Fuji is in the front. If that were the case, the painting would have rather depicted Mt.Fuji.

Therefore, I think that I painted from the Kameari side. The mountains in the back are not the Nikko mountain range, but rather Mt.Tsukuba.

In his picture book Edo Souvenir, Hiroshige depicted the view from the Niijuku side. Across the river on the Kameari side are rows of restaurants. At that time, carp, sea bass, catfish, crucian carp, and other fish were abundant in the Nakagawa River, and there were many restaurants along the river that served these fish, which were a specialty of the area.

Edo Meisho Zue includes a picture looking toward Niijuku from the Kameari side. It shows a cook trying to scoop fish in a tub with a net. The explanation says that this area is called Kameari and that carp from the Nakagawa River is delicious.

Here, I found a website called "Rekichizu. It is a rather easy-to-understand map that shows the street routes of the time. In the Edo period (1603-1867), starting from Nihonbashi, there were five main highways (depicted by the green line), and four other supplementary highways called "Waki Oukan" (side roads). The road where "Niijuku Ferry" is located is one of these side roads, the Mito Kaido.

The Nikko Kaido that left Nihonbashi was shared with the Oshu Kaido until the halfway point, when it was divided into the Nikko Kaido and the Mito Kaido after crossing the Senju post town. The Mito Kaido was further divided into the Narita Kaido when it crossed Niijuku. This Narita Kaido passed under Sakura Castle and continued to Naritasan Shinsho-ji Temple, so it was also called Sakura Kaido.

Here is a current map from the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (GSI). I put Hiroshige's viewpoint on this with a red gradient and the Mito Kaido and Narita Kaido roads. Kameari Village, on the west side of the Nakagawa River, was called "Kameari" in the Muromachi period (1336-1573), and is thought to have been named after the shape of the land, which was raised up like a turtle's shell. In the Edo period (1603-1867), it is said that "Kameari" was changed to "Ari" and became "Kameari" because "kamenashi" was not good luck as it was connected with "nothing" (nashi).

Please see the map from around 1880. The Mito Kaido coming from the Senju direction on the left crosses the "Niijuku Ferry" and then turns around two large reservoirs in a cranked condition before parting with the Narita Kaido. This circumscribed neighborhood was called Niijuku, because it was developed as a new lodging area in connection with Kasai Castle under the control of the Odawara Hojo clan in present-day Aoto during the Warring States period. Furthermore, in the Edo period (1603-1867), after the Mito Kaido became a side road, the area greatly developed as the next post town after Senju and as a follow-up to the Narita Kaido.

Please take a look at the map circa 1900. You can see that "Niijuku Ferry" had already become Nakagawa Bridge in 1884 (Meiji 17), and the railroad was completed. The station for the Joban Line was initially planned to be built in Niijuku town, which was a prosperous lodging town. However, the tremors of the railroad and the fire sparks and smoke emitted from the trains were disliked. In addition, some people thought that the railway would reduce the revenue from the tolls charged by people crossing the Nakagawa Bridge in Niijuku at that time. On the other hand, a local landowner who believed that a railroad station was essential for the development of the Kameari area came forward and donated land for the construction of the station. In the end, no station was built in Niijuku town, and Kameari and Kanamachi stations opened in 1897. If you look closely, you can see that the railroad deliberately avoided Niijuku.

Take a look at this aerial photo from around 1990. Ironically, the railroad brought a great deal of development to the city, and you can see that there are no gaps between the factories and houses.

Today, this area is Katsushika Ward, but Katsushika was originally a generic name for a vast area extending from Ichikawa and southern Saitama Prefecture to Koto Ward.

In addition, as Tokyo City initially adopted the principle of adopting the name of a ward based on the planned location of the ward office, the first draft of the ward name was "Niijiku Ward" since Niijiku-town was the planned location of the ward office. However, due to the possibility of confusion with the area around Shinjuku and Shinjuku Station in Yotsuya Ward at the time, this original proposal was not adopted, and the ward was eventually renamed Katsushika Ward. The current ward office is located in Tateishi, in the area of the former Yotsugi Village.

Let us take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

First, Mt. Tsukuba appears on the left. Below the hazy clouds is the Nakagawa River flowing prodigiously. To the right of the flatboat is the village of Niijiku. Surrounded by pine trees, the opposite bank on the left will be the village of Kameari. Two restaurants, Chibataya and Fujimiya, are depicted there.

Although not depicted in the painting, Fujiya, Nakagawa-ya, and Kameya were also prominent restaurants on the Niijuku side, all of which served carp and sea bass from the Nakagawa River. They all seem to have served carp and sea-bass caught in the Nakagawa River, and they used the two large fish tanks that caused the Mito Kaido Road to turn in a crank shape.

According to an 1843 record, the village had a population of 956, 174 houses, 4 inns, and a wholesale house to manage the people and horses used for loading and unloading, indicating that it was a fairly large village.

I actually visited this location. This photo was taken from the side of the Nakagawa Bridge, looking at the place where the "Niijyuku Ferry" used to be. The buildings in the upper reaches of the river are the Tokyo University of Science and a group of condominiums built on the redeveloped site of the former Mitsubishi Paper Mill. This is the direction of Mt.Tsukuba.

With the Nakagawa Bridge in the background, this photo looks in the direction of Kameari on the old Mito Kaido Road.

This is a photo looking toward Niijuku from Nakagawa-bashi Bridge.

I have tried to fit the current situation into Hiroshige's painting. In Hiroshige's time, "Nijiku" was the busiest village in the area. It was the second post town on the Mito Kaido Road, and was lined with restaurants offering delicious river fish, as well as a wholesale market. I wonder how many people now know the place name "Nijiku" instead of Shinjuku. The times are moving fast, aren't they? The quiet flow of the Nakagawa River seems a little sad.

I visited the place where my favorite "One hundred Famous Views of Edo" was painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scene looks like nowadays.

I visited the place where my favorite "One hundred Famous Views of Edo" was painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scene looks like nowadays.

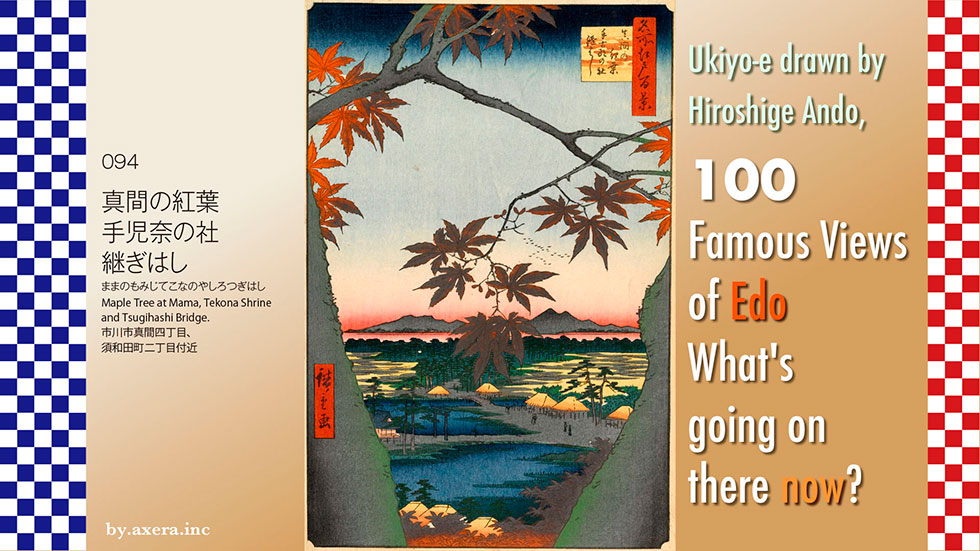

094, "Maple Tree at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Tsugihashi Bridge" is a bit complicated, but it refers to the autumn leaves at a place called Mama, a shrine dedicated to a person named Tekona, and several bridges called Tsugihashi. These are depicted in a single painting.

Furthermore, according to the researcher of this painting, the red color of the pigment used has been oxidized and turned gray, so I corrected the color of the autumn leaves in Photoshop. Please see the picture as it is.

This is a view looking south from Guho-ji Temple on a hill called Mama-yama, north of JR Ichikawa Station. The red gradation is Hiroshige's viewpoint.

Next, please see the map showing the difference in elevation. You can see that the area to the south is much lower than Mt.Mama. You can see that the area painted by Hiroshige is low along the river from east to west.

Please see the GSI map, which is a little more enlarged. I covered this with a map from around 1877. There are still traces of lowered land.

To make it a little clearer, I covered the lower part with light blue. You can see that the south side of Guho-ji, Hiroshige's viewpoint, is like a large inlet. In this inlet, there was a port for the Shimousa National Government, which was located in Konodai. This will be the location for the theme of Hiroshige's painting.

Hiroshige also depicted this place in his picture book Edo Miyage. According to one theory, Tekona was the daughter of an official of the Yamato kingdom around 630. She married into a neighboring country, but due to a dispute between the government of Katsushika and the country where she married, she was resented and returned to Mama, eventually entering the bay at Mama.

This story was the basis for the Tekona legend.

In the old days, the area around Mama was a marshy area where irises and reeds grew here and there, and sandbars were formed here and there, with small bridges called "tsugihashi" crossing them.

In those days, the well water in this area contained salt, so the residents crossed the bridge to a well called "Mama-no-i" (well of Mama), which was a well of fresh water at the foot of Mt.Mama.

Among the people who gathered to collect water, there was one girl in particular, Tekona, who was conspicuously beautiful. She was dressed in a modest linen kimono with a blue girdle, and although she did not comb her hair or wear kimono, she looked purer and more beautiful than any other princess, no matter how well dressed she was.

Tekona's presence spread throughout the Shimousa provincial government, which was located on a plateau deep in the Mama region, and not only young men from the village but also officials of the government and travelers from the Kyoto capital came to court Tekona.

Tekona, however, continued to refuse all courtships. As a result, many of them fell ill because of their continued feelings for Tekona, and many of the brothers quarreled with each other. When Tekona learned of this, she mourned and grieved every day.

That day, as she came to a cove in Mama with her worries, a bright red sunset was just about to fall into the sea. Tekona saw it and said, "If only I were not here, there would be no more conflicts in my short life. Just like that sunset. Tekona went straight into the sea.

The next day, Tekona's corpse was washed up on the beach and buried by the villagers who felt sorry for him. This was Tekona's Okutsugi (tomb), the predecessor of today's Tekona shrine.

In 737, Gyoki Bosatsu (Bodhisattva Gyoki) stopped by the site and, taking pity on Tekona, built Guho-ji Temple, which became the administrative temple of Tekona Shrine.

This legend spread to the capital of Kyoto, where it captured the imagination of Manyoshu poets, and was written into several poems, making the "Mama no Tekona-legend" widely known to the public. Since this place is so famous and mentioned in the Manyoshu, which was established around the 7th century, Hiroshige of the Edo period must have naturally wanted to depict this place in his paintings.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

The large tree depicted at the top is a large maple. Guhoji Temple, Hiroshige's viewpoint, was famous for its beautiful autumn leaves. Beyond the foliage on the two sides, geese fly in the sky, and beyond them are the mountains of Boso. The pointed mountain is probably Mt.Nokogiri-yama. Guhoji Temple was located on a steep cliff, so we can peek at what would have been visible beyond the Boso Mountains.

In front of the pine forest depicted in green is a field of the Ichikawa city, and in front of it is the inlet of Mama, and the bridge across it is the Tsugihashi bridge. You can see that water was still entering this area when Hiroshige saw the scene.

The small shrine on the left is Tekona Shrine, and on the right is a steep staircase leading up to Guhoji Temple. At the bottom left, near a house with only the roof visible, there was a "mama well" with a spring of fresh water, and the original Tekona's tomb was located beside it.

I actually went to this place.

Up the stairs at the back of this revived the Tsugihashi bridge is Guho-ji Temple.

As you climb the stairs and look back, you can see the town down to Ichikawa Station, which is now reclaimed and landlocked.

Although it is not the season for maple trees, this is the current view that Hiroshige would have seen.

I tried to fit this picture into the composition of Hiroshige's painting.

The story of Tekona was so old that even in the Manyo period it was described as "that time long ago," but it was so common knowledge that when everyone saw this painting by Hiroshige in the late Edo period, they could recall the sad story of Tekona.

The Manyo poet Yamabe Akahito came all the way from Kyoto to this place and composed a poem about Tekona, saying, "I cannot help being reminded of the beautiful Tekona. Do we now have the same sensitivity as Yamabe Akito? In today's age of images, what we cannot see is judged as something unknown or untrustworthy.

Is it possible that the evolution of the times can even control our sensibilities?

How do you feel when you see this picture?

I visited the actual location of my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scene looks like today.

I visited the actual location of my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scene looks like today.

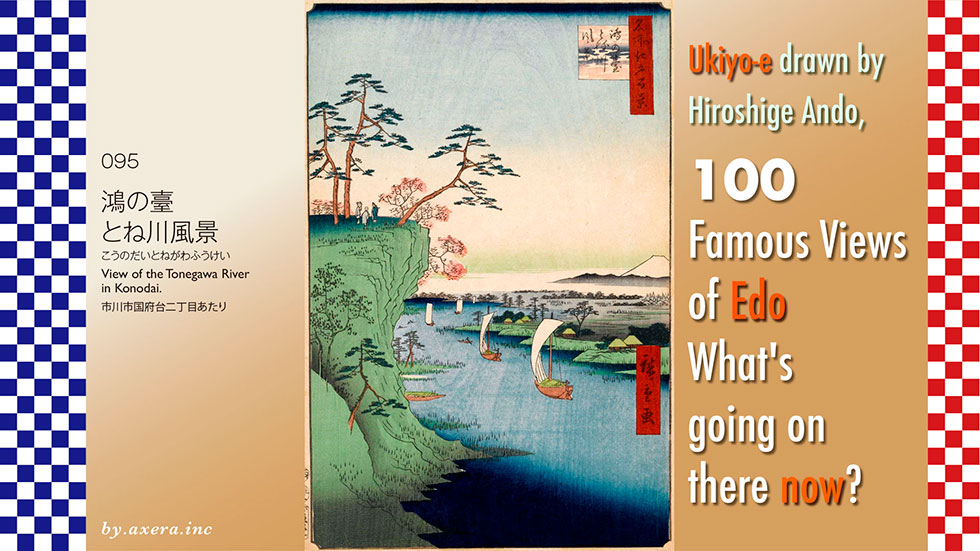

The "View of the Tonegawa River in Konodai" in #095 is a view of the Edo River and beyond from the side of Satomi Park in Konodai. It seems that the character "ko" in Konodai was applied to this character because many storks (ko-no-tori) had been living in this area since ancient times. The bird is now listed as an endangered species, but it was so common in this area for a long time.

Please check this location first. This is where the Edo River makes a big curve just before it crosses the Ichikawa. I added a red gradation to Hiroshige's viewpoint.

I enlarged the map a bit more. It seems that Hiroshige was looking almost directly south from the present cliff bottom of Satomi Park.

I covered this with a map from around 1877. You can see that unlike today, the river was a little narrower and had a levee for protection.

Based on the above, let us take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

First, the waterfront occupying the lower half of the picture is the Tone River, now called the Edo River. Many Takase-bune boats float along the river, which was the main route for logistics in the Edo period. Most of these boats carried goods from the north to Edo.

The village on the right is the current village around Koiwa. Today, Keisei's Edogawa Station has been built here.

The raised platform seen leaning to the left is Konodai. Three Edo watchers are depicted, and pine trees and colored maples are also depicted around them. In fact, this location seems to have had such a good view of Edo Bay and the city of Edo that one can see the entire cityscape.

Fuji is depicted in the middle right. However, as seen on the map, Mt. Fuji is not visible in this direction. It is thought that Hiroshige included Mt. Fuji in the painting as a story based on an anecdote from this neighborhood.

Please see the map showing the elevation differences in this neighborhood. Since ancient times, this Konodai area has been surrounded by the sea and rivers to the west and east, and many ancient burial mounds have been confirmed, indicating that human life has been conducted here since ancient times.

Here is a quick look at the history of the Konodai area.

It is also believed that there was a township of a great clan ruled by Kuninomiyatsuko (a bureaucrat) before the establishment of the Ritsuryo (law) system. The previous Tekona-den theory refers to this period. In any case, Konodai seems to have been a strategic point in the Kanto area.

After the Taika-no-Kaishin Reforms that began in 645, the Shimousa Provincial Government was established here, and at the same time, Kokubunji and other temples were built, creating a grid-like city similar to Kyoto.

In 939, Taira no Masakado, who had no choice but to seek to establish an independent state in the Kanto region after falling for the Yamato court's trickery, attacked Konodai, and the power of the provincial governments in the three provinces of Boso (Kazusa, Shimosa, and Awa) rapidly declined.

In 1180, Minamoto no Yoritomo, who had fled to Nanso after his first defeat, entered Shimousa Province, where he gathered some 30,000 soldiers and marched them to Kamakura, laying the foundation for the establishment of the samurai government that followed.

In 1479, Ota Dokan built a fort in Konodai to defeat the Chiba clan, which later became "Konodai Castle.

From 1538, the Odawara Hojo clan attacked the Boso Satomi clan, which had taken up camp at Konodai Castle twice, and Konodai Castle came under the jurisdiction of the Hojo clan.

In 1590, when Toyotomi Hideyoshi destroyed the Odawara Hojo clan, Konodai Castle came under the jurisdiction of the Tokugawa clan.

However, Tokugawa Ieyasu abandoned the castle on the grounds that a fortress overlooking Edo was dangerous.

In 1663, the Soneiji Temple moved to the site of the former Konodai Castle.

In the Edo period , Takizawa Bakin's novel "Nanso Satomi Hakkenden," which took 28 years to complete from 1814, became very popular. The novel, which begins with the story of Konodai, was already being performed as a Kabuki play during its publication, and it became a story known to all Edo citizens.

Later, Konodai became a popular place for people from Edo to visit as a place related to Tekona's legend of Mama, autumn leaves, old battlefields, and Satomi Hakkenden, as if it were a sacred place for pilgrims today.

It also became popular as a scenic spot from which to view Edo and Mt. Fuji from the top of the cliff, and was featured in many guidebook-like books about Edo, even though it is not Edo.

Here is a look at the relationship between the city of Edo, the river, and the water. This is a map showing the current elevation differences, and the areas in blue and green are lowlands. During the Jomon period, the sea entered quite deep into this lowland area.

As time went on, even when Tokugawa Ieyasu entered Edo and established the Edo shogunate, the situation was still like this.

To see the location of the area in relation to Edo, I put Hiroshige's viewpoint in white gradient on a map that shows a little wider area and height differences.

In the current map, the Arakawa River has been rehabilitated and flows through the area due to river improvement, but at that time, the Tone, Arakawa, Watarase, and Iruma Rivers flowed into Edo Bay in an irrigation system, and the blue and greenish areas on this map were almost always flood-prone areas.

Goods brought by ship from the Kanto region and northward were generally transported from Choshi around the Boso Peninsula and into Edo Bay.This was also an unstable course, dependent on the weather at sea.

In order to rectify this situation, the shogunate initiated the "Tosen Project. In an era when there were no construction machines, it was a grandiose plan to change the flow of several rivers.

Eventually, however, around 1654, the Tone River was successfully diverted at Sekiyado, dividing into two paths, one flowing to Choshi and the other flowing into Edo Bay as the Edo River.

This created a safe and shortened route for transporting goods from the north, up the Tone River from Choshi and down the Edo River from Sekiyado, and the Edo River became the main route for transporting goods to Edo.That is why Hiroshige's depiction of the Tone River shows so many Takase-boats.

Now, I have actually been here.

It is not a cliff, but a large cover of trees. The upper left is Konodai, which has been developed as Satomi Park, and you can go up from behind this. The small railway bridge in the distance is the Keisei Line crossing the Edogawa River.

I took this picture a little further back to the north. Unlike Hiroshige's picture, the real Konodai is not that high.

This is the view looking west from among the trees in Satomi Park. If the weather is good, from this angle, one may be able to see Mt.Fuji.

The current view is framed in Hiroshige's painting.

Among the 100 Famous Views of Edo, this painting is pregnant with various histories. People have lived in this Konodai since ancient times, and as time went by, various people passed by, leaving behind various stories. In Edogawa as well, various people and things passed through every day. Standing in Satomi Park, one can feel these things passing by in the breeze.

Finally, we included storks in the landscape, which are said to bring happiness to the places where they live.

I actually visited the location of my favorite "One hundred Famous Views of Edo" painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scene looks like today.

095 Horie and Nekozane Villages" depicts the villages of Horie and Nekozane, which at that time were located across a narrow tributary of the Edo River that branched off downstream.

First, please take a look at the wide-area Applemap.

This time, the setting is Urayasu City, surrounded by the red dotted line. Urayasu today, with its well-developed transportation network, is popular as a bedroom town close to Tokyo, but in the Edo period, this area can no longer be called Edo. It is also 14 km away from Edo Castle.

Please also see the GSI map, although it is a little harder to understand compared to the Applemap. Let's cover this with a map from around 1878. You can see that the reclamation of Tokyo Bay has progressed amazingly since then.

Please see the enlarged view from Applemap again. It seems that Hiroshige was looking northwest from around Nekozane 2-chome, toward the current Tozai Line and Urayasu Station. The red gradient represents Hiroshige's viewpoint.

See also the GSI's light-colored map at about the same scale.

I covered this with the map of 1878.

I have included Hiroshige's viewpoint and the locations of Urayasu Station on the Tozai Line and the Urayasu IC on the Expressway Wangan Line to make it easier to understand the location. Across the Sakai River, Horie Village was to the south and Nekozane Village to the north, with Toyouke Shrine to the east. To the west of Horie Village, the characters for Dairenji Temple, Hojoin Temple and Seiryu Shrine, which still exist today, can be read.

Horie Nekozane" (096) was one of the first five pictures published in February 1856 as part of the One Hundred Famous Views of Edo series. Why did Hiroshige choose this lonely village with nothing around even in the Meiji era?

Based on these considerations, we will take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

First of all, the upper left is Mt. Fuji, but it is not actually visible in this direction. Fuji is not actually visible in this direction. To see it, one must look further west. If you can see a mountain in this direction, it is the Chichibu mountain range.

The triangular sail pillar seen in the white haze cloud is a Takase-bune anchored in the Edo River with its sails down. The pine forest in the center hides Dairenji Temple, Houjoin Temple, and Seiryu Shrine, and the group of houses in front of them is Horie Village.

The village on the right across the river is Nekozane Village, and the Sakai River running between them acts like an inlet of the Edo River. It is firmly protected by wooden piles and functions like a harbor with many floating tea boats. These boats carried salt and shellfish to Edo.

At that time, Aoyagi shellfish(himegai shellfish) from Nekozane Village was a well-known specialty all the way to Edo. It is one of the indispensable ingredients in today's Edo-mae-sushi as "bakakagai.

Travelers from Konodai upstream would get off the boat here and walk to the right in the direction of Chiba. On the road to the right of Nekozane Village, a father and son who appear to be fishermen returning to Nekozane Village are depicted. Peeking out from the pine forest on the right is Toyouke Shrine.

The original name of this unusual place, "Nekozane," is said to have changed from "ne, kosane," which means "not to pass over the roots," in reference to the wish that waves would not pass over the roots of the pine trees of Toyouke Shrine in this area, which often suffers from flooding.

One of the boats carrying salt from Gyotoku, covered with straw mats, floats on the Sakai River. This boat will continue on to the Edo River, go a little further upstream, and now go west through the Onagi River, a canal flowing in from the left, to Nihonbashi Koamicho.

Tokugawa Ieyasu, who entered the Edo period , was thinking of securing a stable supply of salt in the suburbs of Edo in order to secure salt for the siege of Edo Castle. He turned his attention to Gyotoku, and since then, the salt fields in Gyotoku have been protected as Otehama. It is said that a canal called Onagi River was also excavated for its transportation.

The hunters on the lower right are a pair of hunters targeting plovers gathered on the mudflats on the left. The rope depicted in the painting is the pull rope of a muso-net, and the hunter on the right quickly pulls this rope when he sees plovers coming to him as decoys or bait, and then raises the net and puts it over the plover.

Edo Bay, with its well-developed mudflats, was rich in shellfish, gobies, and other food for birds, and it seems to have functioned as a sanctuary for waterfowl.

I actually visited this location. This is the current view of the city taken from the Egawa Bridge, a bridge over the Sakai River, beyond Hiroshige's point of view. However, Toyouke Shrine is not visible.

I relied on the street view from Applemap.

We also relied on Google Eath.

I combined this Applemap with Google Eath, and then combined it with the Chichibu mountain range seen from the Arakawa River. Please forgive me if the mountains are not this close.

I tried to fit this into Hiroshige's painting.

It is a bit forced, but I think you can get a sense of what it looks like today.

You can see that at the time of Hiroshige, there was almost nothing but the villages of Nekozane and Horie, which have been transformed into a place where houses and buildings are crammed together. The salt fields of Gyotoku also came to an end in 1949. The boats that used to ply the Sakai, Edo, and Onagi Rivers have now been replaced by trucks.

The sea behind Hiroshige's viewpoint was reclaimed much further out, creating the town of Shin-Urayasu, a new Tokyo bedroom community, and at the tip of the sea, the Tokyo Disney Resort, a fairyland that attracts people from all over the world.

Even now, snipes and plovers that migrate from as far away as Siberia and Mongolia in the fall rest their wings on the waterside of Kasai Rinkai Park and Funabashi's Sanbanze in Tokyo Bay, which is gradually being restored.

Aoyagi shellfish, once a specialty of Nekozane Village, now has Hokkaido and Chiba as its main production areas, and after the war, Urayasu is rather more famous for its clams. These grilled clams on skewers called Yakima are expensive but very tasty.

Now, why did Hiroshige introduce Horie and Nekozane in Chiba, which are not in Edo, at the top of his Edo 100 series?

In 1859, after Hiroshige died of an epidemic, a picture book titled "The Fujimi Hyakuzu First Edition" was published. In this book, "Shimousa Horie Nekozane" is included, which has the same composition as "One hundred Famous Views of Edo". Originally, this picture book was supposed to contain more than 100 views, but it was finished with only 20 views, probably because the artist Hiroshige passed away.

In the preface to this picture book, Hiroshige wrote that although Katsushika Hokusai's "One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji" was interesting in the way it was painted, Fuji played a minor role, so I painted realistic Fuji in this book.

This preface suggests that Hiroshige knew that Mt. Fuji, which can be seen from Horie and Nekozane villages, where there is nothing around, is so beautiful that he decided to compete with Katsushika Hokusai by including Mt. Fuji halfway into his picture in "One hundred Famous Views of Edo".

Fuji in "Shimousa Horie Nekozane" in "The Fujimi Hyakuzu First Edition" has been modified to the west direction so that it can be seen properly. This is why Toyouke Shrine, which was located on the edge of the village to the east, is out of the picture angle.

This gives us some sense of how Hiroshige, as a painter, felt about Hokusai.

Now, why did Hiroshige introduce Horie and Nekozane in Chiba, which are not in Edo, at the top of his Edo 100 series?

In 1859, after Hiroshige's death from an epidemic, a two-color illustrated book titled "Fujimi Hyakumizu First Edition" was published. In this book, "Shimousa Horie Nekkozane" is included, which has the same composition as "One hundred Famous Views of Edo". Originally, this picture was supposed to have more than 100 scenes, but it was finished with only 20 scenes, probably because Hiroshige passed away.

In the preface to this picture book, "Fujimi Hyakumizu First Edition", Hiroshige wrote that although Katsushika Hokusai's "One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji" was interesting in the way it was painted, Mt. Fuji played a minor role, so I painted realistic Fuji in this book.

This preface suggests that Hiroshige wanted to include Mt. Fuji in the Edo 100 series, as he half-heartedly painted the mountain in the One Hundred Famous Views of Edo as well. If you look closely, you will see that the direction of Mt. Fuji in "Shimousa Horie Nekkozane" in "Fujimi Hyakumizu First Edition" has been modified to the west direction so that it can be seen properly. Fuji in "Shimousa Horie Nekozane" in "Fujimi Hyakumizu First Edition" has been corrected to the west direction so that it can be seen properly. However, Mt. Fuji is actually located farther to the left.

The "One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji" that Hiroshige compares is a series of black-and-white picture books consisting of one hundred and two pictures of Mt.Fuji.

The large-format nishiki-e "Fugaku Sanjurokkei" (Thirty-six views of Mt. Fuji) by Katsushika Hokusai was put on sale in 1831 and became so popular that another 10 views were added to the 36 that had already been published. In fact, "One hundred views of Mt. Fuji" was produced at the same time. In his preface, Hokusai wrote that he would live to be 100 years old, transcending his profession as an ukiyoe artist to pursue a new world of painting.

On the other hand, Hiroshige also published "Thirty-six views of Mt. Fuji" in 1859, after his death. However, neither Horie nor Nekozane villages appear in that series. Fuji in the foreground of Horie Village, Nekozane Village, and the Sakai River seems to have been a little too far away from the direction of the village.

However, I can only imagine that Hiroshige, as a painter, respected Hokusai and wanted to be as close to him as possible.

I visited the actual location of my favorite "One hundred Famous Views of Edo" painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scene looks like today.

The "Five Pines along the Onagigawa Canal" (097) is a view looking toward the Nakagawa River from above the current Onagi River Bridge.

Please check Applemap to see where Hiroshige painted this picture from. The area circled by the red dotted line is about less than 6 km west of Edo Castle.

Enlarge the map and put a red gradient on Hiroshige's viewpoint. Hiroshige would have looked south down Yotsume-dori from Sumiyoshi Station on the present-day Toei Shinjuku Line and east from about the top of the Onagigawa Bridge over the river.

Let me cover this map with an old map from the Tempo era. At that time, the Onagi River Bridge was not yet in place, and the five pine trees and the words "Kuki Shikibu Shoyu" can be seen on the right side of Sarue-cho, where Hiroshige painted the famous pine trees as the main theme.

In this area, five pine trees were planted along the canal, hence the name of the place, "Gohonmatsu (pive pines)". Later, four of the pine trees died, leaving only the pine tree of the Kuki family, the feudal lord of the Ayabe domain in Tango Province, which grew to reach the Onagigawa Canal. The lush pine trees became so large that they covered the surface of the water and were considered rare and famous in Edo.

Here is a map of the area as it was in the Edo period on "Rekichizu".

The Onagigawa Canal, which runs in a straight line from east to west, was opened around 1590 by Tokugawa Ieyasu, who established Edo Castle as his residence, and ordered Onagi Shirobei to open a canal to Gyotoku in Shimofusa Province in order to secure salt as a food source for his troops. Later, the canal was also used to transport tourists to Konodai, Mama, and Sakura, as well as visitors to Narita-san Shinshoji temple, and was used for transportation other than salt. It is said that at that time, it took about half a day to travel the 13 km from Edo to Gyotoku by boat.

In 1629, the Onagigawa Canal was widened along with the Tone River's eastward shift project. The so-called eastbound sea route of goods, which had previously bypassed the Boso Peninsula, was now carried from Choshi up the Tone River, from Sekijuku down the Edo River, and via the Onagigawa Canal to Nihombashi, becoming an artery for the distribution of goods to Edo.

Hiroshige also depicted these five pine trees in his picture book Edo Souvenir. The perspective of this painting is the view looking toward Edo from the east, but the bridge depicted immediately behind the pine tree in this painting does not exist. There is a new Takahashi bridge quite a bit further on, but it should be depicted as about a small bridge because of the distance.

The bridge beyond that would be Takabashi, which is about 2 km away, so this painting is depicting something that is not visible.

Next, please take a look at the Edo Meisho Zue by Saito Gessin, which also depicts the Five Pines. You can see a magnificent pine tree protruding from the house of the Kuki family on the left, so that it crosses over the black fence and spans the Onagigawa Canal. Even the three pillars supporting the pine tree branches extending from the river's edge are accurately depicted. A man who looks like a monk on a boat called "Gyotoku-bune" heading east is soaking his hand towel in the river, probably because it is hot. The Onagigawa Canal, which actually flows in a straight line, has a gentle arc on the left side, perhaps adjusted for the painting.

The small bridge seen beyond the boat is the Oshima Bridge over the Yokojukken River, beyond which the row of houses has partially retracted to the left, with small pine trees planted on both sides. Here stands a koshindo (a Buddhist shrine) and a stone monument with directions to the temple of Five Hundred Arhats. Turn left here, and you can reach the temple in about 300 meters.

Hiroshige painted two other views of the Onagigawa Canal in his "One Hundred Famous Views of Edo": Mannenbashi Bridge at Fukagawa in view 56, a view of Mt. Fuji from the bridge just before the Onagigawa Canal exits into the Sumida River; and Nakagawa River Mouse in view 72, a view of a strategic transportation point where the Nakagawa and Onagigawa Canals intersect. The "Five Pines along the Onagigawa Canal" is located right in the middle of the Onagigawa Canal.

Let's take a closer look at the painting by Hiroshige.

The magnificent pine tree protruding from the large left is the pine tree overhanging the Kuki family's mansion. It is supported by piles extending from the edge of the Onagigawa Canal, which is protected by wooden piles, isn't it? A man who looks like a monk on a boarding boat heading toward Gyotoku is dipping his hand towel in the water, just like in Edo Meisho Zue.

Beyond the shoreline on the left is depicted a slight depression in the wall of a private house, and a little further on is what appears to be a small bridge. If this is the Oshima Bridge and the hollow is the approach to the Five Hundred Arhats Temple, the positions are reversed. After the second pillar supporting the pine tree, what appears to be a temple is depicted, but it seems to be the Five Hundred Arhats Temple. This, too, would be misaligned.

The pine trees occupy nearly 20% of the painting. However, if you look at the actual calmness of the scene, the pine trees are overemphasized. The height of the pillars supporting the pine tree makes it look like a ridiculously large tree. But, well, this is also a composition typical of Hiroshige.

I actually went to this location. This is the view from the Onagigawa Bridge. The pink wall on the far left is the current Shimachu Home Center, and the Kuki family mansion was located just at the end of the wall. This is where the pine trees were planted. The blue bridge in the back is where it crosses the Yokojukken River and where the Oshima Bridge used to be. It is now the Onagigawa Clover Bridge that crosses the two canals.

On the north side of Onagigawa Bridge, the location of this photo shoot, there is a relocated signpost from the temple of Five Hundred Arhats, which once stood at the end of Oshima Bridge. According to the inscription on the back of the monument, this was rebuilt in the 2nd year of Bunka (1805), so this is a stone monument that Hiroshige and Saito Gessin would have actually seen.

In the space near the river on the monument, several young pine trees are planted along with a stone pillar engraved with "the site of five pine trees". The Asahi Shimbun newspaper reported that the pine trees actually painted by Hiroshige were cut down in 1909 after soot from a nearby factory killed them.

The current view is inserted into Hiroshige's painting. In addition, although the branches are not very large, I added a reproduction of a pine tree at the base of the Onagigawa Bridge.

In researching Hiroshige's paintings and maps of the time, I wondered if he really went to this place and painted this picture. This is because the location of the objects in Hiroshige's painting is too similar to that of Edo Meisho Zue, and the location of the objects in Hiroshige's painting is also out of alignment.

Further research revealed that Hiroshige had obtained permission to use the design from Saito Gessin, who drew the Edo Meisho Zue, when he drew the One Hundred Famous Views of Edo series. I see, then it is understandable that the paintings are so similar. Although we will not know the truth until we interview Hiroshige himself, it seems that he did not visit this Five Pines, but drew it based on Edo Meisho Zue.

I visited the actual location of my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scene looks like today.

In "Fireworks at Ryogoku" (098), the Ryogoku Bridge and fireworks are seen from Yanagibashi Bridge, where the Kanda River flows into the Sumida River.

First, please check its location on Applemap. Just 3 km east-northeast of the Edo Castle keep, the Ryogoku Bridge crosses the Sumida River.

I enlarged the map a little and added Hiroshige's viewpoint in red gradient. A little north of Ryogoku Bridge, the Kanda River flows in from the west, and a small bridge called Yanagibashi Bridge crossed the Kanda River just before the confluence. It is said that Hiroshige may have painted the fireworks seen from this bridge.

I covered this with an old map of the time. This is a fire prevention area that was built to prevent fires from spreading in Edo, where fires were common.

This vacant lot was called Ryogoku Hirokoji, and was lined with reed-bedecked restaurants that could be dismantled at any time, making it the busiest shopping area in Edo. Hiroshige painted a bird's-eye view of the Ryogoku Hirokoji from the west. You can see how bustling it was. I added Hiroshige's viewpoint here as well, using a red gradation.

There is also a painting by Hiroshige that was painted from a little closer to Hirokoji. Beyond the bridge, there is a smaller fire-escape, and beyond that is Ekoin, where sumo tournaments seem to be held.

Furthermore, Hasegawa Settan also painted a similar picture in Edo Meisho Zue. I have included Hiroshige's viewpoint here as well, using a red gradation. The length of the bridge and the number of people are a bit exaggerated, but it seems that the fireworks at Ryogoku were exceptional for the citizens of Edo.

With these images in mind, let's take a closer look at the actual Hiroshige painting.

The first impression is that it is dark. To emphasize the fireworks and the lights of the boats, the rest of the picture is almost entirely dark. If you look closely, you can see many Edo citizens enjoying the fireworks on the bridge. The bright lights of the lanterns on the boats, large and small, convey the feeling that the party is at its peak.

The large boat in the center is a houseboat, and its interior seems to have been about 20 tatami mats in size. The boats with lanterns on their bow ends were boats that sold snacks and drinks to customers. Smaller boats were boats with boars and roofs, and some boats performed Shinnai-song, Gidayu-song, and Kagee-pictures for the pleasure boats with customers on board. It looks like fun to watch.

The black painted sky depicts fireworks, but fireworks in the Edo period were extremely plain compared to today's fireworks. Fireworks were made only from saltpeter, charcoal, and sulfur, so the only colors available were gold, orange, and red. The fireworks themselves were not large, showy displays, but rather "meteors," which were parabolas that fell down in a continuous motion.

The fireworks were popular for the way they hung down like willow branches after they went up, and people enjoyed seeing them with their eyes and tasting the sound of the launch and the smell of the gunpowder at the same time.There was also the fun of a live concert as we know it today, with everyone in the audience calling out "tamaya" and "kagiya" together to enjoy the sense of togetherness.

The open firework on the upper right is called "Waremono," which is a firework made of iron that began to be used in the Ansei era (1854-1844), and after breaking, it falls down while glowing white. It probably leads to the current flower-shaped fireworks.

In this painting, Hiroshige depicts Ryogoku Bridge as seen from a boat.

Ryogoku Bridge was built in 1659 in the wake of the Great Meireki Fire (1657), and at that time it spanned a little further downstream than it does today. Initially called Ohashi, the bridge was later officially renamed Ryogoku-bashi because it spanned both Musashi and Shimousa provinces.

It was not until 1733 that fireworks began to be displayed annually on Ryogoku Bridge.

In 1735, a drought caused a poor rice harvest, and in 1735, a massive outbreak of locusts led to a severe famine, which caused rice prices to skyrocket and a cholera epidemic that killed nearly one million people in Edo. The 8th shogun, Tokugawa Yoshimune, therefore held a "kawasegaki" to mourn the souls of the dead.

On May 28, Kyoho 18, 1733, or July 9 according to the solar calendar, the shogunate held a water god festival on the opening day of the Ryogoku river in order to pray for the spirits of the dead and to ward off bad luck, as was done the previous year. The origin of the Ryogoku Fireworks Festival is said to be the fireworks that were set off during the festival.

This painting, one of Hiroshige's last works, depicts Ryogoku Bridge as seen from Manpachirou, a ryotei restaurant in Yanagibashi. Although no fireworks are depicted, it is said that the viewpoint of this painting is almost the same as the location of the "Ryogoku Fireworks" painted in 100 Famous Views of Edo.

Earlier, Hiroshige also painted Manpachirou as seen from the outside. Looking at this, it seems that Manpachirou was located on the corner of the Asakusa side of Yanagibashi Bridge.

The Ryogoku Fireworks Festival was a very popular event for Edo citizens, and many ukiyoe prints have survived. Please see these in succession.

The left is a Fireworks by Hiroshige II, and the right is a joint work by Hiroshige I and Toyokuni. The right painting is centered on a woman rather than fireworks.

This is a painting of the Sumida River by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, painted around the time of the Tempo Era (1868-1912), in which a boat pulling up to a simmering vendor boat has a geisha-like woman playing a shinnai (a traditional Japanese folk song). In addition, six men on their way back from a pilgrimage to Mt. Oyama are approaching from the right, swimming in a shower of fire sparks, making the painting very humorous.

Keisai Eisen depicts moonrise and fireworks over a slightly deformed ryotei from Yanagibashi Bridge at dusk.

The last is a painting of a very happy-looking fireworks display by Utagawa Kunimitsu, a master artist of Hiroshige's lineage, painted during the Bunka era (1868-1912).

Now, I actually went to this location. This is the current Ryogoku Bridge, which has moved upstream a bit since that time.

This is a view of the present Ryogoku Bridge from a little further downstream, south of what was then Ryogoku Hirokoji.

This is a view of Ryogoku Bridge from Yanagibashi Bridge around 1881. The ryotei, Manpachirou, from Hiroshige's viewpoint, appears to have been on the left in the photo.

This is the night view of Ryogoku Bridge as seen from around Yanagibashi Bridge today.

Fireworks were combined with this image and inserted into Hiroshige's painting.

The Ryogoku Fireworks Festival, which used to be held here, was repeatedly cancelled and resumed for various reasons before being moved upstream to the Kototoi Bridge area, where it continues to be held to this day. The name was changed from "Fireworks at Ryogoku" to "Sumida River Fireworks Festival".

"Fireworks at Ryogoku" was also included by the 8th Shogun, Yoshimune, as a prayer to ward off bad diseases, but ironically, it was cancelled for three years due to the recent new type of coronavirus infection.

"Fireworks at Ryogoku" was unveiled in August of 1872, but in September Hiroshige himself contracted cholera and passed away.

In August 1897, the wooden parapet of the Ryogoku Bridge fell due to the weight of spectators, resulting in a catastrophic accident that killed and injured many people. This accident led to the Ryogoku Bridge being moved to its current location and rebuilt as an iron bridge.

Since then, the Sumida River Fireworks Festival has been broadcast live on TV by TV Tokyo since 1978, and has recently become an annual summer event.

In this way, fireworks have been a medicine to cheer people up since the Edo period. I hope it will continue for a long time.

Finally, please enjoy the final video of the 2016 Adachi Fireworks Festival.

I visited the actual location of my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scene looks like now.

Kinryuzan Temple in Asakusa" (099) is a view from Kaminarimon in Asakusa, looking toward the snowy Niomon Gate.

First, please check the location on Applemap. Asakusa is about 1 ri (about 4 km) northeast of Edo Castle.

Let me enlarge the map a little and show Hiroshige's viewpoint in red gradient. You can see that we are looking from the Kaminarimon gate, almost to the north, toward the Hozomon gate.

At the west end of Komagata Bridge is Komagata-do, where the main statue of the Holy Kannon was found in the early days, and where the standing statue of the Horse-headed Kannon is now enshrined. In the past, visitors coming by boat used to disembark here and pay homage to Komagata-do before heading to Kannon-do.

After finishing their visit to Komagatodo, visitors went straight north, passing through the Kaminarimon gate, then the Hozomon gate, and finally the main hall. In the area that is now Nakamise, there were not stores at that time, but rather a row of six temples of Sensoji Temple, one for each of the six branch temples.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting. First, there is a large lantern hanging from above, which was dedicated by San'emon, a representative of the roofers of Shinbashi, who collected money to dedicate it, under the rule that the person who dedicated it could write any character he wanted.

The many people heading toward the back of the temple on the approach flanked by the child temples, amidst the falling snow, are depicted in this painting, which conveys the bustling atmosphere of Senso-ji Temple. The red building in front is the present Hozomon Gate, which was called "Niomon" in those days because the Kongorikishi statues were enshrined on both sides of the gate.

To the right of it, the five-story pagoda, also painted in vermilion, is depicted. The painting was published in July of the 3rd year of Ansei (1854), and the nine rings that were bent by the earthquake the previous year have been repaired. Some researchers believe that the overall white and red coloring of the painting may be due to the fact that the nine rings that were bent by the earthquake were repaired without incident.

Although the artist is unknown, there remains an ukiyoe that looks like a modern news report titled "Sensoji Daito Kaiyaku" (Sensoji Temple Great Pagoda Unbent), which depicts a nine-ring pagoda that was bent by an earthquake. This is a bit funny, however, because it says that the damage was less severe than the mysterious bending of Hokanji Temple in Yasaka, Kyoto, because of the divine power of the Sensoji Kannon.

Please take a look at the changes in this painting over time as it was printed. The first printing reflects Hiroshige's opinion, but in subsequent printings, the tints and gradations have been changing rapidly, whether due to the publisher's opinion or the needs of the times. This may be due to the fact that the white and red congratulatory effect of the restoration of the nine rings may no longer be necessary.

Hiroshige painted the entire Sensoji temple in three linked panels. The main hall is in the center, the Niomon gate is to the right, and the five-story pagoda is in the back, but the Kaminarimon gate is further to the right in the painting, so it is not visible.

Hiroshige also depicted the origin of Sensoji Temple in his paintings.

According to the "Senso-ji Engi," a legend of Senso-ji Temple, early in the morning of March 18, 628, the 36th year of the 33rd Emperor Suiko, a brother fisherman was casting a net around the present Komagata Bridge when he found a statue of Buddha in the net. When he showed it to Haji-no-Nakatomo, a member of a wealthy local family, he discovered that it was a statue of Sho-Kannon Bosatsu (Bodhisattva), and Nakatomo himself became an ordained priest and built a hall on the east side of the present Komagata Bridge. This is said to be the beginning of Sensoji Temple.

This is Komagata-do, which has now been moved a little to the north as the original building of Senso-ji Temple. In 1590, Tokugawa Ieyasu, who entered Edo (now Tokyo), designated Senso-ji Temple as a place of prayer and gave it a territory of 500 koku (about $500), but the temple was frequently destroyed by fire. The Senso-ji Temple, which was also close to places of entertainment for the common people, developed further as the "Kannon-sama (Goddess of Mercy) of Asakusa.

In fact, there was a later story about this Kannon that went up from the Sumida River.

It is said that the statue of Kannon, which was enshrined in Iwaido, located along the Naruki River in Iwabuchi, Hanno City, Saitama Prefecture, was washed away by a large body of water. The Iwaido Kannon is said to have originated around the time of the 26th Emperor Keitai (450-531), when a traveling monk, whose name has not yet been recorded, obtained spiritual inspiration and erected a statue of the Sho-Kannon and a hall on a rock face exposed along the Naruki River. However, during the reign of the 27th Emperor Ankan, a storm occurred and this hall and the statue of Sho-Kannon Bosatsu were washed away into the Naruki River.

The statue of the Sho-Kannon Bosatsu would have taken more than 100 years from the night of the storm, flowing about 75 km from the Nariki River through the Iruma River and the Arakawa River to Komagata on the Sumida River. It is said that when the people of Iwabuchi Township at that time heard the news that the statue of the Sho-Kannon Bosatsu had been found in the Sumida River, they asked for its return, but their request was not granted.

However, time passed, and Kyoshun Shimizutani, the 24th head priest of Sensoji Temple, regarded this oral tradition as historical fact, and on September 15, 1933, he returned the statue of the Sho-Kannon Bosatsu from Zenryuin, the first of Sensoji Temple's branch temples, to Iwaido-Kannon. That was somewhat of a relief.

I have actually been to this location. This is the present Kaminarimon Gate.

It is the gate at the entrance to the main approach, and is officially called "Fujin-Raijinmon" (Gate of Wind and Thunder Gods), as it enshrines a statue of the Wind God in the right room and a statue of the Thunder God in the left room. It was destroyed by fire in 1865, nine years after Hiroshige's painting was published.

It was rebuilt in 1960 with reinforced concrete construction. It was donated by Konosuke Matsushita, the founder of Panasonic Corporation. An engraving of Matsushita Electric Works can be seen on the metal part under the lantern.

The Tokyo Sky Tree can be seen on the east side of Kaminarimon Gate.

After passing through the Kaminarimon gate, both sides of the street are lined with stores known as nakamise. Until the Edo period, the stores were lined by the child temple of Sensoji, but they are allowed to open their stores on the promise that they will maintain the approach to the temple.

This is the Hozomon Gate, and during the Edo period it was possible to ascend to the second floor several times a year. This gate was rebuilt in 1964 and is a reinforced concrete structure. It was once also called "Niomon" because of the Kongorikishi statues enshrined on either side of the gate.

The five-story pagoda to the left of the Niomon gate is the five-story pagoda that was visible to the right of the Niomon gate at the time of Hiroshige. It was reconstructed in 1973, is made of reinforced concrete, and is approximately 48 meters high.

This is the main hall, also called Kannon-do, as it enshrines the statue of Sho-Kannon, the principal image of the hidden Buddha. The present hall was rebuilt in 1958 and is a reinforced concrete structure. The old hall was rebuilt in 1649 with the support of the third shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu, and was designated a national treasure as a representative example of a large temple hall from the early modern period, but was destroyed by fire during the Tokyo Air Raid in 1945.

The upper part of the sign was destroyed by fire in the Tokyo Air Raid of 1945, but was replaced in 2020 by a sculptor from Iba, Japan. The word "Semui" means "to save sentient beings by removing their fears and awe through the power of the bodhisattva. I am very grateful for this.

I have tried to fit the current painting into Hiroshige's painting.

Although it is quite different from Hiroshige's snow scene painting, it has regained much of its vitality after the Corona disaster.

As you may have already noticed, almost all of Sensoji Temple's buildings were recently rebuilt. 300 bombers dropped 330,000 incendiary bombs on the densely populated downtown area, including Sensoji Temple, in the early morning hours of March 10, 1945. This was the Great Tokyo Air Raid.

War is a mechanism for the genocide of human beings. Yet somehow, wars still do not disappear. It seems that there are people in this world who really want to wage war. Kannon, the Goddess of Mercy of Asakusa, I ask you to do "Semui" to these people. Please save them.

I visited the actual location of my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see how the scene looks today.

The 100th work, "Nihonzutsumi Enbankment at Yoshiwara," depicts the causeway known as the Nihon Zutsumi and the bustling crowd of customers heading to the Yoshiwara licensed quarters from a little higher up.

First, please check where you are using Applemap.

It is about 5 km northeast of Edo Castle. At that time, this area was on the outskirts of Edo, and there were few houses, and almost only fields and rice paddies. Yoshiwara Yugaku was also called "Kannon-ura," because it was built on a part of the rice field behind Sensoji Temple.

Please see a more enlarged map. I will put Hiroshige's viewpoint in red gradient. When Tokugawa Ieyasu came to Edo, the right half of this map was almost a flood plain because the Irumagawa, Arakawa, and Tonegawa Rivers were flowing in and out of the city.

Later, due to the Tonegawa River's eastward shift project by the Edo Shogunate and flood control projects including the Arakawa River, the amount of water decreased, but the city of Edo was also always in danger of flooding. In 1621, an embankment was constructed from Imadobashi Bridge in Asakusa Shoden-cho to Jokanji Temple in Minowa to the northwest, using the soil from the collapse of Mount Matsuchi. This is the Nihonzutsumi Enbankment. The map shows it as a dark blue line.

In 1617, shortly after the establishment of the Edo shogunate, a recognized brothel called Yoshiwara was permitted in the area around present-day Nihonbashi Ningyocho, but it was destroyed by the great fire of Mereki (1657). The shogunate ordered the relocation of the brothel itself, rather than rebuilding it, since the Ningyocho area had already become quite residential. Asakusa paddy field by the Nihonzutsutsumi was the candidate for the site. This new officially recognized brothel was called Shin-Yoshihara to distinguish it from Nihonbashi. It is shown in green on the map.

I have covered this with a map of the time, roughly matching the location.

At that time, visitors arriving by boat on the Sumida River entered the Sanya moat, which ran along the north side of the bank from Imadobashi Bridge, and disembarked on the way. From there, they walked along the bank of the Nihonzutsumi to the entrance of Shin-Yoshiwara, Yoshiwara Ohmon gate.

You can see from this map that the Shin-Yoshiwara licensed quarters at that time were surrounded by a moat, forming a completely different world.

This is Hiroshige's bird's-eye view of the Shin-Yoshihara prostitute from the north. The lower left is the main gate at the entrance, and the upper right is the dead-end gate on the Asakusa side. The main street, Nakanocho, was planted with cherry trees in spring.

If we look at this on a map showing all the stores in Shin-Yoshihara, we can see that it is drawn from the upper right. On this map, Nihonzutsumi is on the right. Still, the scale of the officially recognized brothel, Shin-Yoshihara, is amazing.

This is a view of Shin-Yoshihara from the sky looking toward the Nihonzutsumi. In the foreground are the stores of Shin-Yoshihara with their turrets raised, and beyond them are people walking or riding on palanquins along the Nihonzutsumi toward Shin-Yoshihara. The black tree on the left is the Reward willow.

In a series of what looks like a modern restaurant guide, Hiroshige depicts a store called Harimaya, which was located at the entrance to Shin-Yoshihara. People are coming from the back right toward Shin-Yoshihara, over the Nihonzutsumi. On the left is the Reward willow, and turning left here leads to a slightly winding street called Emonzaka, where Harimaya was located at the entrance. The Nihonzutsumi, Reward willow, Emonzaka, and Ohmon gate were all places through which customers heading to Shin-Yoshihara must have passed.

Here you can see what it actually looked like in the Meiji era. This photo was taken in the early Meiji era from Mount Mitsuchi, showing Imadobashi Bridge, the ryotei Ariake-ro, and the Sumida River beyond. Customers coming by boat on the Sumida River entered the Sanya moat from here.

Beyond the Imado Bridge, the Imado Shrine can be seen, and we go under the bridge in the direction of Shin-Yoshihara. Since the tide is high and low, we used to get off the boat here when the tide was low and walk to Shin-Yoshihara.

This photo was taken from Nakanocho-dori, the main street, during the cherry blossom season, looking toward the Ohmon gate at the entrance. It is strangely realistic to see umbrellas and futons hanging out to dry.

The large gate of Shin-Yoshihara was replaced by an iron gate in 1881. The row of buildings in the back are called Hikitechaya, which is a kind of information center where customers are escorted to and from the brothels and where they are served with sake. In Shin-Yoshihara at that time, it was customary for first-class prostitutes not to take their customers directly to their establishments, but to use this teahouse as an intermediary.

Kadoebirou" was a prestigious establishment in the Shin-Yoshiwara licensed quarters that was the first to build a three-story wooden grand building. Only the name remains today.

Now then, let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

The first thing that appears at the top is the sine moon and geese flying at an angle. The moon at this angle means that it is around 8 or 9 o'clock in the evening, before the closing of the Yoshiwara Ohmon gate. However, in reality, it seems that people were able to enter and leave even after closing the gate at midnight, since they were able to use the small side gate even after the gate closed.

Beyond the hazy clouds, to the left is the direction of Ootori-jinja Shrine. The tree on the far right is the Reward willow tree, and if you turn left at this point, you will reach Emonzaka, which leads to the Ohmon gate, the entrance to Shin-Yoshihara.

From the lower left, the causeway of the Nihonzutsumi continues, and even at this hour of the day, people are constantly passing by. There are many teahouses with reed screens lining the street, hoping to attract customers. It seems like a scene from a peaceful country. If you look closely, you can see that most of the people are wearing haori, which means they were dressed in what we now call suits, and they came here to have fun.

I actually visited this location. This is the location where Hiroshige's point of view was taken, looking toward Senzoku from the intersection of the Sanya moat and the Mikata bridge, which has been culverted. The actual viewpoint of Hiroshige is from a little higher up.

This is a photo looking toward the entrance of Yoshiwara from what was then Nihonzutsumi, now Dote-dori. Instead of the bank, which was empty on both sides, it is now lined with buildings on both sides.

This was the Sanya moat at that time, which was culverted and turned into a park. This Sanya moat was also the discharge channel from the Otonashi River in Oji at that time.