I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by my favorite artist, Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like today.

061, "Pine of Success at Onmayagashi Embankment on the Asakusagawa River," is a picture looking toward Azuma-bashi Bridge through a well-shaped pine tree called Shubi no Matsu (Pine of Success=beginning and end), which used to be located at the east end of what is now Kuramae-bashi Bridge.

First, please check out Hiroshige's viewpoint from Applemap. It is represented by a red gradient.

I combined it with an old map of the time and put it on top.

This comb-shaped area was the rice storehouse of the Shogunate, called the Asakusa Okura. There was a wharf for storing rice brought by ship from the Tenryo, and at the tip of the wharf in the middle of the wharf, there was a pine tree with its branches sticking out into the river. At the tip of the wharf, there was a pine tree with its branches sticking out of the river, and who called it the "Shubi no Matsu.

The north side of this area was called the Onmaya river bank, as the stables of the shogunate were located there, and boats were built to cross to the other side of the river, which was called the Onmaya river bank ferry. Nowadays, this is just the Umayabashi bridge.

Now let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

First of all, hanging large from the upper left is the "Shubi no Matsu". To the left of it, there is a hedge of green bamboo, and to the right of the roof below it, Azuma Bridge can be seen in the distance. To the right of the Azuma Bridge is the streets of Honjo. On the river side, "Ureshinomori" is drawn in black.

The Sumida River is lined with many boats, and the two simple boats are the ferry boats of the Onmaya river bank. The small boat to the left is a high-speed boar boat, probably carrying passengers on their way to Shin-Yoshiwara. The large roof boat on the left has a bamboo screen down and a faint shadow of a person is floating on it. Since the shogunate regulated the use of yakatabune for ordinary people, the roof boat was introduced instead, a small boat with enough space for two people to sit opposite each other and have a drink.

In those days, there were two types of ukiyo-e: first printing and post-printing, and each craftsman used a slightly different coloration and blur. In these two postprints, the silhouette of the bamboo screen on the roof boat is clearer.

The silhouette of the roof boat is clearer in these two postprints, and it looks like a Geigi is having a drink across from a lord. There were many merchants called "fudasashi" living in this area, who were in charge of the management and transportation of rice storehouses for Hatamoto and Imperial family members. It is said that "fudasashi" merchants, who later became wealthy in the financial industry, used to float their roof boats in this place. It is said that these merchants often floated their roof boats here. So this painting looks very glamorous.

This place was also a pathway for boar boats heading to Yoshiwara. It was the usual course for visitors coming up from the lower reaches of the river to go up at the Imado Bridge and walk along the road beside the Sanya moat to Yoshiwara. It is said that when the boats came to the bottom of this pine tree, they would discuss the outcome of the day, hence the name "Shubi no Matsu (Pine of Success=beginning and end)".

Hiroshige's picture book, Edo Souvenir, also features this "Shubi no Matsu".

The painting depicts a geisha standing on a roof boat, Ryogoku Bridge, and the Shiinoki-yashiki on the left. The Shiinoki-yashiki was the upper residence of Matsuura Bungono-kami of the Hirado Nitta clan, and within the residence there was a forest of Shiinoki trees, which was called the "Ureshinomori". They used these vertebrate trees for the New Year's gate pines. Today, it is open to the public as the former Yasuda Garden.

The map depicts this viewpoint.

This is a composite of tile prints installed on the Sumida River terrace and painted by Katsushika Hokusai, depicting the "Shubi no Matsu" and the "Shiinoki-yashiki" on the opposite bank, and Edo citizens fishing in front of it in summer. Since the Asakusa River upstream of the Onmaya river bank was closed to fishing, front of Asakusa Okura was a famous place for fishing, and Edo citizens enjoyed fishing there. It looks like a lot of fun.

The area around the pine tree was well known for its delicious clams and fish, which grew up eating the rice that sometimes overflowed into the river when it was unloaded.

The map depicts this viewpoint.

The painting on the left is the "Shubi no Matsu" as seen from downstream, painted by Ryuryukyo Shinsai, a student of Katsushika Hokusai. This gives you a good idea of what the pine tree looked like. A little above the pine is Komagata Hall, above that is the main hall of Sensoji Temple, on the right is Azuma Bridge, and above that is Mount Tsukuba.

The painting on the right depicts the "Shubi no Matsu" as seen from the ryotei (Japanese restaurant) Tokiwaro by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, a great painter of beautiful women. In the back, the "Ureshinomori" on the opposite bank is also depicted.

In the painting on the left, Utagawa Toyokuni depicts plays, actors, and poems related to "Shubi no Matsu". The painting on the right depicts one hundred beautiful women fishing in the river in front of the "Shubi no Matsu".

This beautiful woman seems to be wearing black teeth, so she must be a former geisha from the Yanagibashi area with a husband, and the other fishing rod on the left side of the boat must belong to her husband. It is a picture of a beautiful former geisha who has caught a good husband. It could be taken as the story of the roof boat in Hiroshige's painting. The picture in the upper left frame shows "Shubi no Matsu" and the "Ureshinomori" forest on the other side of the river. It is interesting that the square tray and bowl are already prepared, as if they were going to eat right away.

I actually went to this place. It is about 20 meters downstream from the current Kuramae Bridge, and it looks like this, with the Kuramae Bridge standing right in front of us.

A little further downstream, it looks different. The Lion Institute and the Sky Tree are quite a nice collaboration.

This is what it looks like from upstream. The riverbank has been developed as a walking path called Sumida River Terrace. The namako (sea cucumber) wall on the bank gives it a "Kuramae" look.

The seventh generation of "Shubi no Matsu" has been restored next to Kuramaebashi Bridge.

The first generation was destroyed by wind in the An'ei era, the pine tree that was planted from there also died in the Ansei era, and the pine tree that was planted three times also died in the Meiji era. After that, it was destroyed by fire in the Great Kanto Earthquake and World War II, and the sixth generation was planted in 1962.

In fact, I tried to fit the current view into Hiroshige's painting.

It's a nice painting, but it looks more like the inside of a city than a river.

I put the plantings of the Sumida River terrace in the foreground to create the image of pine trees, but this is also a far cry from Hiroshige's painting.

This was the place to show off their "Shubi (heads)". It was a place for the men on their way to the brothel to discuss their earnest wishes and their successes. It was also a place for geisha to show their hopes and achievements by boat, to see if they could catch a good husband. In this painting, the sky is brightening like the dawn in the distance. Could this be the light of hope? And if the head of the boat turned out well, what we could see was the "Ureshinomori (Happy Forest)" on the other side of the river. This was literally the place of the "Shubi (heads)" where you could see from the beginning to the end.

I visited my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scene looks like today.

I visited my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scene looks like today.

The "Komagatado Hall and Azumabashi Bridge" (No. 062) is a view looking toward the Sky Tree from Azuma-bashi Bridge over Komagatado hall, which was located at the west end of Komagatabashi Bridge.

Komagata-do is currently located on the north side of Komagata-bashi bridge west, up from Asakusa station on the Toei Subway Asakusa line. This is the point circled in red. When Hiroshige painted it, it was located a little further south, in the middle of Asakusa-dori where Komagata-bashi Bridge crosses.

Hiroshige's viewpoint is represented by a red gradation.

I will cover this map with an old map of the time. There are some positional differences and distortions, but you can get a glimpse of what it was like in those days.

Komagatado Hall was located on the banks of the Sumida River about 300 meters straight south of Kaminarimon Gate.

Through Komagatado, Hiroshige depicted the Sumida River, the streets of Honjo, Azuma Bridge, and the Hosokawa family's residence in Kumamoto on the east side of the bridge.

The west side of Komagatado faces the Oshu-kaido road, and on the west side is the Sumida River. This Komagatado faced the river direction in the early days, but at this time it was facing that Oshu-kaido road. In the old days, the main gate of Senso-ji Temple was located here, and visitors to the temple would come by boat to the riverbank, climb up from the side of the Komagatodo, join hands with the Komagatodo, and then walk along the tree-lined path to the main hall via the Kaminarimon Gate.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting from above.

The first thing that appears is a bird flying in the dark sky. This is a Hototogisu(toad lily). In the Sumida River, the cicadas begin to sing about 15 days after the first day of summer, which was called "Hatsune (first sound). This bird symbolizes the arrival of summer.

It is also said that the bird was painted to evoke a phrase from a letter sent by Kohya Takao II, a Yoshiwara prostitute, to Tsunamune Date of Sendai, with whom she had just parted: "Nushi wa komagata atari wo hitotogisu"(I guess you are still around Komagata). This phrase was also a famous love story known to everyone in Japan at the time.

Below it, a red rag flutters in the rain. This is the signboard of Beniya Hyakusuke, a haberdashery shop selling white powder and rouge, located just across the street from Komagatado Hall. A red cloth was tied around the end of a long pole to advertise the shop so that it would stand out even from a distance high in the sky. The sign read, "Does your store sell white powder to nymphs?" It is said that Edo citizens made fun of him.

On the other side of the river is the Honjo district, and just across the Azumabashi Bridge is the residence of Hosokawa Notono-kami of the Nitta clan in Kumamoto. Many rafts and boats carrying goods were passing by on the Sumida River, giving a sense of life in those days. On the right side, a stored lumber is standing, indicating that there were many lumber dealers in this neighborhood.

At the bottom of the painting, in front of the front, is the riverbank, where many boats can be seen moored. The area between this riverbank and the intersection of Komagatado and Oshu-kaido road is a little wider, and there appear to have been tea stalls and the like.

Now, please take a look at the differences in printing in Ukiyo-e.

In the first print, rain clouds are beautifully depicted using the "atenashi bokashi" technique to express a sky that looks as if it is about to start pouring. The same is true of the smoke rising from the townhouse. Also, the rain that has begun to fall is depicted as thin white streaks.

In later printings, however, the blurring became less and less pronounced, and the rain was drawn in black. The color and pattern of the title in the upper right corner also differs, as does the overall color, coloring, and quality of alignment. It seems that different printers and engravers have completely different ways of expressing their work.

This is another painting by Hiroshige depicting Komagatado hall. The left image shows citizens pounding rice cakes next to Komagata-do, indicating that Komagatadohall was located on a stone wall for a seawall. The painting on the right depicts a long vertical line from the pine tree at the head of the river downstream to Komagatado Hall and Senso-ji Temple.

The painting on the right depicts Komagatado hall, Sensoji Temple, Azumabashi Bridge, the forest of Masaki Suijin no Mori, and Mount Tsukuba in the distance, from the pine tree at the head of the river, also downstream.

The painting on the left is Komagatado hall by Eisen Keisai, but the shape is slightly different. Although the title of the painting is "Komagatado," it may have been painted in a different location.

This painting is part of a triptych by Katsushika Hokusai, with the Onmaya riverbank on the left and Komagatado on the far right. The signboard of Beniya Hyakusuke, with its red cloth held high, is also depicted. If you look closely, you can see a slight difference in the form of the mimetic bead part of the Komagatado. You can also see that the front of the river bank is stepped.

To the left of the Komagatado, you can see a small "Kaisatsuhi", a monument that forbids the killing of fish in the area. This monument was erected in March of the 6th year of the Genroku era (1693) and still remains today.

This painting is Edo Meisho Zukai by Setsutan Hasegawa. It is a bird's-eye view of Komagatado from the river side, and you can clearly see its position in relation to its surroundings. When seen from the river by boatmen, Komagatoado looked like a white horse running, so it was called "Koma-Kake," (meaning "horse running") which then became "Komakata". This picture is an old map, and this is the angle from which you see it.

This painting depicts the entire Sensoji temple by Totoya Hokkei, a Kano school teacher turned student of Katsushika Hokusai. You can clearly see the relationship between Sensoji Temple and Komagatado. In the days when there were no airplanes, the area around Sensoji Temple must have looked like this when seen from the sky.

Sensoji Temple was founded when the main statue of Kannon Bosatsu (Goddess of Mercy) was scooped up with a net by a fisherman fishing in the Sumida River. The statue was first enshrined in the small hall located here, around Komagata-do.

Later, in 942, the Komagatado hall was built as a place of worship to express gratitude to and protect the fish living in the Sumida River, and to enshrine the Bato Kannon, a guardian deity of living creatures. Eventually, a "Kaisatsuhi" monument was placed and the Sumida River in this area was declared a no-fishing zone.

The main deity, Bato Kannon (Goddess of Mercy), is a rare example of the Kannon, with its eyes lifted up in the corners, its hair in a rage, and its fangs bared. As the guardian deity of horses and a god of travel, the temple was worshipped by travelers on the Oshu-kaido road in front of it, and was so famous in Edo that no one knew of it.

I actually went to Komagatado.

This is the present Komagata-do hall. The hall at that time was destroyed by fire in the Great Kanto Earthquake, so it was built afterwards. The hall, which was white at the time, is now red. The stone wall that surrounded the building was relocated and became what it is today.

This is a photo from a bit further back. The blue bridge on the right is Komagata Bridge, and Komagatado hall was located right in front of it. The white building to the left of Komagatoado is the famous Mugitoro Restaurant.

This is the stone pillar sign that still remains to the south of the hall, which is the "Kaisatsuhi" monument that forbids the killing of animals in the area.

This is a picture of Komagatado hall from the back. Today, between the Sumida River and Komagatado, there is a path leading to Azuma-bashi Bridge and a private house.

I actually tried to fit the current view into Hiroshige's painting. However, Azuma-bashi Bridge is not visible from Komagatodo today. Therefore, I combined Azumabashi Bridge and Komagatado as seen from Komagatabashi Bridge. It turned out to be an interesting picture.

Although now merged, there was a town called Batou in Nasu-gun, Tochigi Prefecture. The family of a local businessman donated a collection of paintings by Hiroshige Utagawa and other works to open the Batou Hiroshige Art Museum. Designed by architect Kengo Kuma, the museum is a wonderful place to view many works of art, including Hiroshige's paintings and prints.I wonder if this is also related to the Bato Kannon, which has a frightening appearance.

I visited one of my favorite works, "Meisho Edo hyakkei" (One hundred Famous Views of Edo) by Hiroshige Ando to see how the scene looks today.

Ayasegawa River and Kanegafuchi Pool" (063) depicts the confluence of the Ayasegawa River on the opposite bank from Shioiri Park in Arakawa Ward, where the Sumida River makes a sharp curve.

Please first check its location from a modern map.

I added a red gradient to Hiroshige's viewpoint.

The Sumida River, winding its way from the upper left, turns a little to the north when it crosses the JR line, and then turns sharply to the right and heads south. At this point, the Ayasegawa River flows in from the northeast.

The end of the river now meets the present-day Arakawa River, which has been greatly widened, but there was no Arakawa River in the Edo period. Here is a map from the Tempo period superimposed on the map. You can see the relationship between the Sumida River and the Ayasegawa River, although it is quite distorted.

Let's superimpose a more solidly scaled map of the early Meiji period on this one.

The Ayasegawa River changed its course over time, and by this time had become a narrow river, flowing into the Sumida River, or Arakawa River at that time. The Ayasegawa River also merged with the Tonegawa River coming from Kurihashi around Koshigaya, and repeatedly overflowed every time there was a heavy rainfall. Because the course of the river changed so much, it was called the "suspicious (ayashii) river," which is said to have become the Ayasegawa River. There is also a theory that the river became the Ayasegawa River because the water flow undulated from side to side, making the river's course look like twisting threads of twine. In any case, this area was a perfect flooding source.

The Ayasegawa River at this time had its headwaters in the Okegawa, which until before the Edo period was the main stream of the Tonegawa and Arakawa Rivers. Even today, the river, known as the former Arakawa River, flows through Okegawa and Konosu before emptying into the Nakagawa River east of Koshigaya. Part of this is the old Ayasegawa River.

This map shows the flow of the river before Tokugawa Ieyasu entered Edo. The red lines are the Tonegawa River and the Arakawa River, which together flowed into Edo Bay. The shogunate initiated a plan to move the Tone River, which caused flooding in Edo, to the east, and the Arakawa River to the west. By the time Hiroshige painted this picture, the Tonegawa River had been gradually shifted eastward from the Nakagawa River to the Edogawa River, and finally diverted around Satte, so that most of the water would flow toward Choshi, as the Tonegawa River does today. So it was a tremendous construction project.

Around Kumagaya, the Arakawa River was bent to the west, merging with the Iruma-gawa River and the Shinkagishi-gawa River, and renamed the Sumida River so that it would flow into Edo Bay.

And this is the current state of the Tonegawa and Arakawa Rivers. The Tonegawa River joins the Kinugawa and Watarasegawa Rivers and flows almost entirely into Choshi. The Arakawa River joins the Iruma-gawa River and flows into Kasai as the Arakawa River, which has a large river width.

Please see the map circa 1920.

A plan was underway to divide the Arakawa River, which had flowed from Chichibu and had become the Sumida River, around Akabane where it joined the Shingagishi-gawa River, and to discharge it as the Arakawa drainage channel to the Kasai area. As a result, the wandering Ayasegawa River was completely divided, and the river mouth depicted in Hiroshige's painting became a small channel connecting the Arakawa River and the Sumida River. In this map, the Ayasegawa River still remains as a waterway in the whitewashed Arakawa River discharge channel.

Before it was divided here, the Ayasegawa River was so beautiful that fireflies were said to fly over it. However, as Japan entered a period of rapid economic growth, large amounts of domestic and industrial wastewater flowed into the river, and for 15 consecutive years from 1980, the Ayasegawa River was ranked as the worst first-class river in Japan in terms of water quality, and its name became well known throughout the country. The Ayasegawa River, now divided, flows along the Metropolitan Expressway Route 6 and empties into the Nakagawa River, which flows parallel to the Arakawa River.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

The first thing that appears is a silk tree with fluffy pink flowers. This tree grows wild on the bank by Kanegafuchi, on the right side of the painting, and is famous for its blossoms, which people from all over Edo came to see before summer. In the composition, Hiroshige seems to have made the tree grow from the Shioiri side on the opposite side of the river.

Below it, a white heron is depicted flying up. The waterfront in this neighborhood was a flood plain, so there were many wetlands with reeds. This made it an ideal feeding ground for waterfowl. The mouth of the Ayasegawa River can be seen below, and the Ayase Bridge is also depicted in a small size.

Across the Ayasegawa River, Sekiya-no-sato is on the left, Kanegafuchi is on the right, and Horikiri is behind it. The Sumida River extends in the foreground, and this area was called Kanegafuchi because a bell (kane) was sunk here. It is said that Yoshimune, the 15th shogun of the Tokugawa shogunate, ordered the bell to be raised around the time of the Kyoho period, but gave up the idea because of the swirling water at the bottom of the river.

A boatman on a raft is depicted on the river, standing poised and maneuvering the raft. At that time, there were many wholesale dealers in the Senju area who handled lumber brought in from upstream, bundling it into rafts and transporting it away as requested. Two cargo boats are depicted on the left, indicating that the Arakawa, or Sumida River, played an important role in the transportation of goods.

"Edo Meisho Zue" by Hasegawa Setsutan depicts the entire area from Hiroshige's point of view in a bird's-eye view. The painting titled "Kane-no-fuchi, Tancho-no-ike, Ayase-gawa" shows that the area around Kanegafuchi was a sandbar and a famous spot for fireflies. Since "tancho" is another name for firefly, fireflies must have been abundant in this area from the time when the flowers of the silk tree were no longer in bloom.

Ihachi Subaru-ya also painted this area in a similar composition. An odaijin (a government official) and his apprentice, who may have come from a ryotei restaurant in the nearby Mokubo-ji Temple area, are bringing food to see the silk tree. In this area, flowers such as violets, bridegroom's head, clay pencils, and nazunas bloom all at once in spring, and many people visited the area by boat.

Kisai Rissho is composed in the same way as Hiroshige, but the silk tree grows from the right side. It is clear that the tree is from the Kanegafuchi side, but this is also a little too compositional.

In 1926, Takahashi Shotei painted a woodblock print of a night scene of the Ayasegawa River and Ayase Bridge in the snow. The painting is a wonderful depiction of an empty, quiet world, but as you can see on the map, the huge Arakawa River drainage project was steadily underway just upstream at the time.

I found a photo of the Ayase Bridge from a period slightly before this. It is a collection of photos issued in 1919.

I also found a photo, probably around the time Hiroshige painted it. It is thought to be a view from the mouth of the Ayasegawa River on the Kanegafuchi side, looking in the direction of Hiroshige's viewpoint. In reality, the viewpoint is hidden by the sandbar.

Now, I went to this place in modern times. This photo was taken from the top of the bank of Shioiri Park. In the center is the mouth of the Ayasegawa River, and the Metropolitan Expressway Route 6 runs over it. 300 meters from the mouth of the river, the river meets the present-day Arakawa River. The left side of the river mouth is a shipyard.

This is a photo looking downstream. The bridge at the end of the promenade is the Shirahige Bridge, to the left of which is Metropolitan Expressway Route 6, and behind it is the Metropolitan Shirahige Complex. This was planned as a firewall in case of emergency.

This is a photo looking upstream from the bank. Beyond the Senju-Akebono-cho apartments are Keisei-Kanoya Station and Tobu-Ushida Station.

This is a silk tree, which would have grown in abundance in this area at that time. I took this picture of one that was in the neighborhood. It produces fluffy flowers with pink tips before summer.

I have actually tried to fit the current appearance into Hiroshige's painting.

It is a symbolic painting that says that since Ieyasu first came to Edo, various developments have been carried out for the sake of human beings, and now it has turned into such a mess. The original Ayasegawa River, the mouth of which is blocked off by a road, is a mere connecting waterway surrounded by a huge spillway, with no place for even waterfowl, let alone fireflies, to live. It is also a place that makes one wonder what development for human beings is all about. This is truly a "suspicious (ayashii) river.

I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando, one of my favorite artists, to see what those scenes look like today.

I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando, one of my favorite artists, to see what those scenes look like today.

The "Horikiri Iris Garden" (No. 064) depicts a sightseeing iris garden in Horikiri, which at the time was experiencing a gardening boom that attracted many people to the area.

The location is the area of Horikiri Village, which was located exactly 8 km northeast of the present Imperial Palace and Edo Castle at that time.

Today, it is located where the Sumida River makes a large right curve and re-approaches the present-day Arakawa River, on the east side of the Horikiri Junction of the Metropolitan Expressway.

When Ieyasu entered Edo, the current large Arakawa River was not yet in existence, and the Sumida River, the Arakawa (Ayase River) of that time, and the Tone River gathered around this area as they merged, becoming a major source of flooding. However, being a source of flooding meant that a very fertile marshland was promised, so the area has been developed as fields and rice paddies since ancient times. Since the castle of the Kasai clan was located in Horikiri, the area was known as "Kasai Sanmangoku" during the Edo period (1603-1868), and in addition to rice cultivation, vegetables and flowers were also actively produced in the area. Iris, brought from Asaka-numa in Oshu-Koriyama at the end of the Muromachi period, was especially famous.

Around 1800, father and son Izaemon, a peasant farmer who lived here, began to cultivate irises in earnest. As a result of their enthusiastic cultivation, they created Japan's first tourist iris garden, "Kodaka-en," during the reign of Izaemon II. It is said that Hiroshige may have painted this Kodaka-en. On the map, it is on the east side of the present Horikiri-Shobuen. It is about the right edge of the blue circle.

In fact, if you zoom in on an old map from the time Hiroshige painted this picture, you will see that along the banks of the Ayase River, it says, "This is a famous spot for irises by Izaemon, a farmer in Horikiri Village." It is a famous place for iris in Horikiri Village. You can see that this place was so famous that it appeared on maps of the time. I have shown Hiroshige's viewpoint in red gradation.

In fact, let us take a closer look at the painting by Hiroshige.

First of all, three different types of irises are depicted in a wide blue sky. It is recorded that Izaemon II, riding the wave of the gardening boom of his time, imported various types of irises from all over Japan and propagated them. It is thought that Hiroshige therefore intentionally painted different types of irises.

In the distance, a forest of water deities along the banks of the Sumida River is depicted in blackish color. In the foreground is the appearance of Suda Village, with Mokuboji Temple in the middle and the Sumida River Shrine with its rather large roof to the left of it, and on the other side is Hashiba no Watashi, where one could cross the Sumida River. In the foreground, Edo citizens who would have come to view the iris from Hashiba-no Watashi are depicted enjoying themselves, and it is said that there was a zigzag wooden path under their feet.

If you look closely, you can also see various types of irises in the distance.

By the way, in Japan, we call iris Ayame, Shobu and Kakitsubata separately, but in English, they are all called iris. What Hiroshige painted is Shobu.The difference between these three types can be seen at the base of the petals. Ayame is the one with reticulated petals, Shobu is the one with yellow streaks, and Kakitsubata is the one with white streaks.

Now, we have prepared Hiroshige's first and second prints. However, the first print has lost its original coloring and is somewhat dull. I imagine that the colors were a bit more vivid at the time of printing, so I made some color adjustments to the later prints.

Izaemon II modeled the garden on the Kakitsubata Garden in Yatsuhashi, Chiryu City, Aichi Prefecture, which was mentioned in the Ise Monogatari of the Heian period (794-1185), and made various innovations so that visitors could walk around the garden. One of them is a zigzag wooden path called Yatsuhashi. In addition, these ukiyoe show that the garden was also equipped with a hill and an arbor.

Around 1840, Izaemon's iris garden came to the attention of the Tokugawa family, and with the promise not to provide food or drink, it was officially approved as a tourist iris garden and opened as Kodaka-en. Later, other farmers' iris gardens opened in the area, attracting many writers and artists.

In the Meiji era (1868-1912), in addition to the first Kodaka-en and Musashi-en, a number of tourist iris gardens were opened, and their reputation continued until the early Showa era (1926-1989). In 1942, Kodaka-en, the founder of the tourist iris garden, closed its doors, and iris cultivation in Horikiri came to an end.

Now, I visited the current Horikiri Shobuen. This iris garden was restored in 1953 by replanting iris plants that had been evacuated. Later, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government acquired the garden and reopened it as the Tokyo Metropolitan Horikiri Shobuen. The location is about 300 meters west of where Kodaka-en was located.

In 1977, the garden was transferred to Katsushika Ward, and in 2018 it underwent a major renovation and now has about 6,000 iris plants of 200 varieties.

I have inserted this photo of the current iris garden into Hiroshige's painting and further processed it a bit.

The iris was discontinued for a time due to urbanization and war. Now, admission to the garden is free, so please visit in June. You can enjoy the quiet and peaceful atmosphere and catch a glimpse of the scenery loved by the writers and artists of the time.

I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando, one of my favorite artists, to see what the scene looks like now.

I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando, one of my favorite artists, to see what the scene looks like now.

The "Inside Kameido Tenjin Shrine." (No. 065) is a view of the Taiko-bashi Bridge seen through the flowers descending from the wisteria trellis at Kameido Tenjin.

First, let's check its location on AppleMap. Kameido Tenjin is located about 5 km east-northeast of the then Edo Castle and about 1 km southeast of the current Tokyo Sky Tree.

If you zoom in a little on the map, you can see that it is about a 15-minute walk from JR Kameido Station.

If you zoom in more, you can see that the topography seems to have been left almost exactly as it was then. Entering from Kuramae-bashi-dori on the south side, pass through the torii gate and cross the Shinji Pond by two bridges to reach the main hall. Hiroshige is thought to have viewed the building from the east side of the first bridge, called Otoko-bashi, over the pond. I have used a red gradation to represent Hiroshige's viewpoint.

This is what it looks like in AppleMap's Street View. It is completely surrounded by houses, but you can clearly see the wisteria trellises of the Shinji Pond are nicely assembled.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

The painting begins with a gradation of red sky, followed by wisteria flowers hanging from a wisteria trellis. On the other side, a large warped wooden bridge is depicted.

The bridge is now made of concrete, but at that time it was made of wood and was built to resemble the original Dazaifu Tenmangu Shrine.

In fact, the blue coloring under the bridge was originally supposed to be the same color as the skin tone up the bridge. However, it is said that Hiroshige gave the wrong instructions to the printer, resulting in this coloring. This coloring was corrected in later printings. Please see the later printing together.

On the other side of the bridge, Edo citizens are depicted relaxing under a wisteria trellis. Around the precincts of the shrine, there were many sake shop and teahouses for visitors to enjoy the local specialties, such as clam soup and carp dishes cooked right after being taken out of the fish tank. Kameido was often compared to Tsukuda-jima as a wisteria viewing spot. Although Kameido is actually farther away from Edo, it is said that many Edo residents visited Kameido Tenjin for the food and the magnificent wisteria trellises.

The lower half of the screen depicts Shinji Pond, with stone walls, pine trees, and swallows, symbolizing the seasons, on the water and in the sky. At that time, pine trees grew wild in the Gyotoku and Ichikawa area.

Hiroshige drew this bird's-eye view of the entire Kameido Tenjin. The right side of the bird's-eye view is today's Kuramae-bashi Street, and the left side is the main hall. On the lower left is the entrance to the shrine, which is accessed by stairs from the Yokojuken River, a canal, and a small torii gate.

Around 1646, a priest from Tenmangu Shrine in Dazaifu, Kyushu, carved a statue of Tenjin out of a flying plum branch associated with Sugawara no Michizane, and traveled around the country with it as a missionary. He finally arrived at Honjo Kameido Village, which was still Katsushika in Shimousa Province at the time, and placed the statue of Tenjin in a small shrine, which was the beginning of Kameido Tenjin.

It was the famous "Furisode Fire" that turned this Kameido Tenjin into the tourist attraction it is today. During the reign of the fourth Tokugawa shogun, Ietsuna, "the Great Meireki Fire" of 1657, which occurred in the New Year, reduced approximately 60% of "the city of Edo" to ashes. This forced the shogunate to redevelop the east bank of the Sumida River, and Kameido Tenjin, which at the time had only a small shrine, suddenly came into the spotlight. The shrine's precincts were also improved, with a Shinji-ike pond, a drum bridge, a hall and other structures modeled after those at the headquarters in Kyushu.

From there, Kameido Tenjin became a tourist attraction in Edo, and was called "Higashi Zaifu Tenmangu Shrine" or "Kameido Zaifu Tenmangu Shrine" as the eastern part of the city, attracting many visitors, who were depicted in many ukiyoe paintings by artists.

While searching for old photos of Kameido Tenjin, I found one that looks like it was painted by Hiroshige. This photo was taken in 1911, about 50 years after Hiroshige painted the picture.

I actually went to this place. This photo was taken almost from the point where Hiroshige would have painted. The wisteria trellises were not so good this year, but the red drum bridge is impressive.

Still visited by many tourists, this is the main hall of Kameido Tenjin today.

I took this photo of the flat bridge in the middle of Shinji Pond over the wisteria trellis. Even now, the well-maintained wisteria trellises around the pond provide a spectacular view as summer approaches.

I looked around from the top of the Taiko Bridge.The citizens of Edo, seeing the paintings of Kameido Tenjin by the painters, longed to eat delicious food under the flowers hanging from the wisteria trellis. By the time the swallows were flying overhead, the wisteria trellis had become even more famous than the plum blossoms, and visitors flocked to Kameido Tenjin to see the wisteria trellis.

I inserted a photograph of the present-day Kameido Tenjin into Hiroshige's painting. You cannot see the teahouse on the other side of the river, and in the background, the sky is covered with buildings that have been completely converted into residential areas.

I changed the photo to include the shrine pavilion and the new tourist attraction, Tokyo Sky Tree. This one may capture a more modern version of Kameido Tenjin.

Tenjin-sama, initially a small shrine, grew larger after the "Furisode Fire" and attracted Edo citizens with its "wisteria flowers," which had little to do with Lord Michizane Sugawara.

Japan's unique religious beliefs as represented by Hatsumode (New Year's visit to a shrine), you can understand how interesting it is from these paintings and photos. It is quite different from the religious view overseas, and tourists never revere the god Sugawara Michizane from the bottom of their hearts, but visit Kameido Tenjin just to see the beautiful wisteria flowers.

On the other hand, the Shinji Pond, with its floating green algae, is now being swamped by an enormous number of non-native species of "Mississippian tortoises". Here again, the Japanese people's selfish pity for living creatures and their view of life and death are well expressed.

Tsunayoshi V, the next shogun after Ietsuna who developed Kameido Tenjin, was the very man who issued the famous "decree of mercy for all living creatures". I wonder how Tsunayoshi's thoughts ended up in this situation.

I actually visited and saw how the scenes of my favorite "Meisho Edo hyakkei (One hundred Famous Views of Edo)" painted by Hiroshige Ando are now.

I actually visited and saw how the scenes of my favorite "Meisho Edo hyakkei (One hundred Famous Views of Edo)" painted by Hiroshige Ando are now.

The "Spiral Hall, Gohyaku Rakan Temple." of 066 depicts the Gohyaku Rakan Temple and Sanso-do, which were located around the current Nishi-Oshima Station of the Toei Shinjuku Line, and a distant view of them. Because the pronunciation of "Sanso" was similar to that of Sazae, Sanso-do was called "Sazai-do" (Spiral Hall) and had become a famous place in Edo that attracted many visitors.

Let us first check its location. The Five Hundred Arhats Temple (Gohyaku Rakan) is located about 6 km west of the then Edo Castle. Today, Shin-Ohashi Dori runs east to west, just north of Nishi-Oshima Station on the Toei Subway Line. The river running horizontally on the lower side of the screen is the Onagi River, and below the Komatsugawa Line of the Metropolitan Expressway running above is the Katagawa River.

This is covered by an old map of the time. The Katagawa River at the top of the screen is a canal connecting the Sumida River and the Nakagawa River, and the old map shows "lumber yard" along its shore, but Hiroshige's painting clearly depicts this location. I have used a red gradation to represent Hiroshige's viewpoint.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting. It looks like a pre-summer scene with four birds that look like larks flying in the sky and pine trees and cedars depicted in lush green.

In the distance is a timber tree standing in a wood yard along the Katagawa River. To the right are the villages of Nakanogo and Kameido, and in front of them are rice fields.

The observatory on the right side is the third floor part of the Sanso-do, or Sazai-do, of the Gohyaku Rakan Temple. It was possible to see all the way to the left to Mt.Fuji. The road where the teahouse is located is now Meiji-dori Avenue, and if you go to the upper right, there was Gonohashi Bridge, and if you go to the lower left, there was Onagi River. The road is painted with Edo citizens happily dressed in various outfits.

In Edo Meisho Zue, Hasegawa Settan depicted Gohyaku Rakanji Temple in considerable detail. Even discounting the fact that it is depicted in an exaggerated manner, it is clear that the temple had a vast site in Kameido Village. The left end of the painting in the overall picture is Sanso-do. Gohyaku Rakan statues were enshrined in the main hall and the corridor-like East and West Arhat halls on either side of it, and it was devised so that visitors could worship all the Arhat statues through a one-way passage. Please enjoy Settan's panoramic and quite detailed depiction of this scene.

The Five Hundred Arhats (Gohyaku Rakan) are statues in the form of 500 disciples of the Buddha, and there are wooden and stone statues still extant throughout Japan. Originally, the saints in India were praised as "arahants" after they had attained the perfection of true wisdom through ascetic practice and the elimination of worldly desires. When Buddhism was introduced to China, the pronunciation of "arahant" was retained and the word "arahant" was used. As the use of the word became accustomed, the "a" was dropped and the word "arhat" came to be called "arhat. Here is a flash of some of the stone statues of 500 arhats at Kita-in Temple in Kawagoe. You may find an arhat that looks like you.

This temple of the Obaku school of Zen Buddhism was founded in the Genroku era (1688-1704). From the age of 23, Shoun Genkei was a student of Zen master Tetsugan Dokou, a Zen priest of the Obaku school of Zen Buddhism who was famous for his efforts to help local residents in Osaka. One day, he saw a stone statue of 500 arhats at Rakanji Temple in Buzen Province (Honyabakei-cho, Nakatsu City, Oita Prefecture) and decided to create his own statue of 500 arhats. In 1691, while collecting funds through begging for alms and other means, he began to create 536 statues, including five hundred arhats, on his own.

Meanwhile, in 1695, Tsunayoshi, the fifth Shogun, granted him the name of a temple and a plot of land near Kameido Village, where he established Tenonsan Gohyakuarakan-ji Temple. Shoun Genkei enshrined all the arhats and other statues he had carved himself here.

In 1726, during the reign of the third abbot, Gohyaku Rakanji completed a large temple complex consisting of the main hall, the East and West Rakan halls, and the Sanso-do hall. The Sanso-do, which was the center of this temple, was also called "Hyaku-kannon" because it was a building made of three layers, which was rare in the Edo period, and enshrined the Kannon of the hundred temples of the 33 temples in the western part of Japan, 33 temples in the Bando region, and 34 temples in Chichibu. Inside the building, a spiral passageway led up to the temple, and the passageway down to the temple was one-way, so that all the Kannon could be seen when making a round of the building. On the third level, there was a 10-meter-high balcony-like viewing platform, which was very popular among Edo citizens because of its unobstructed view of Mt. Fuji in the distance, making it very popular among Edo citizens. It is like the Tokyo Sky Tree today.

Katsushika Hokusai also depicted this view in his Fugaku Sanjurokkei (Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji). It often depicts Edo citizens enjoying the view, which extends as far as Mt.Fuji.

This Sanso-do Hall does not exist today, but the only one similar to it in Japan remained in Aizu. It is a hexagonal three-tiered hall with a height of about 16.5 meters erected on Mt. Iimori in Aizuwakamatsu City. The official name is "Entsu Sanso-do", and worshippers can visit the 33 Kannon by visiting this hall, which is a one-way structure with completely different pathways for going up and down. It is called "Aizu Sazae-do" and was designated as a National Important Cultural Property in 1995.

I actually went to this place.

At the same location, there was a rather cozy Rokanji temple surrounded by buildings. In fact, this is not the Gohyaku Rakanji temple painted by Hiroshige and his colleagues. In the Ansei Earthquake of 1855, the Gohyaku Rakanji Temples suffered great damage, including the collapse of the East and West Arhat Halls. There is a record that the Sanso-do Hall was also so badly damaged that restoration was impossible. Since this picture was published in Ansei 4, it means that Gohyaku Rakanji was already in serious trouble.

From Hiroshige's point of view, would the angle look like this?

After the great earthquake, the place where Gohyaku Rakanji Temple was located was on reclaimed land and was frequently flooded, causing the temple to decline rapidly. In 1875 (Meiji 8), Sanso-do was demolished and sold along with the statue of Hyaku-kannon. In 1887 (Meiji 20), it was moved to Honjo Midorimachi. In addition, in 1908 (Meiji 41), it was relocated again to Meguro Fudo Aside.

In front of Nishi-Oshima Station, only a stone pillar and an explanatory plaque remain of Gohyaku Rakanji Temple site. It is said that in 1903, Shoanji Temple of the Soto sect of Buddhism was relocated from Okutama-cho, Nishitama-gun to a part of the site of the current Gohyaku Rakanji Temple, which was renamed Gohyaku Rakanji Temple in 1936.

Please see the Applemap aerial photo that zooms in on this area. The area in red is the current Gohyaku Rakanji temple.

In the beginning, Rohanji Temple owned a plot of land in this area of 6,000 tsubo (approximately the size of the Tokyo Dome). The current Gohyaku Rakanji temple has less than 200 tsubo, at the best estimate.

If we compare this with the current topography, Gohyaku Rakanji Temple must have looked like this at that time.

I tried to fit the current photo into Hiroshige's painting.

The picture is a fairy tale from long ago, and one can clearly feel the loneliness of the temple. The temple, which originally had no parishioners, was supported by the Obaku school's unique fucha cuisine, begging for alms, and donations in the early days, but it was unable to overcome repeated disasters and flood damage, and gradually declined. I guess famous places are doomed to disappear unless they continue to be maintained.The temple has moved to Meguro and is now a monolithic temple of the Jodo sect, with both a danka and a cemetery, not of the Obaku school of Buddhism. The temple still preserves 305 of the 536 arhat statues created by Zen master Shoun Genkei, and although there is a fee for admission, visitors can see the arhats, which hide tremendous energy, up close and personal.

I visited my favorite "Meisho Edo hyakkei" (One hundred Famous Views of Edo) painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what those scenes look like today.

I visited my favorite "Meisho Edo hyakkei" (One hundred Famous Views of Edo) painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what those scenes look like today.

The "Sakasai no Watashi" (Sakasai Ferry) in No. 067 is a slightly elevated view of Sakasai Ferry, which was located where the current Komatsugawa line of the Metropolitan Expressway crosses the Nakagawa River. The Edo Shogunate did not build bridges over the river as much as possible at that time for defense purposes. This is one of many such bridges.

Please check the location of this bridge on Applemap. It was located about 7 km west of Edo Castle. Nowadays, the Arakawa River runs in a large north-south direction immediately to the east, but at that time, this Arakawa River did not exist, and the Nakagawa River flowed in a large meandering path as the largest river in this area.

As you can see if you zoom in on the map, south of the Komatsugawa Line of the Metropolitan Expressway is Shin-Ohashi Dori, and the Toei Subway Shinjuku Line runs almost parallel to it, and the station is located almost above ground from Higashi-Oshima Station, almost on the Nakagawa River.

The red gradient represents Hiroshige's viewpoint.

Beyond his line of sight is the metropolitan Oshima Komatsugawa Park, and to the north and south of it is a forest of metropolitan housing and other buildings.

If you switch Applemap to Street View, you can get a better idea of the size of the area.

To understand how they were able to create such a large park, please see the map from 1970. It is because both banks of the Nakagawa River at that time formed a large factory area, and later the Tokyo Metropolitan Government purchased this area and redeveloped it on a large scale.

Next, please take a look at the pictorial map of the time when Hiroshige painted this picture. The circled point is Nihonbashi. Travelers leaving Nihonbashi head north toward Odenmacho and enter the Oshu Kaido. From before the Kanda River, turn right and cross the Ryogoku Bridge.

To the south of the river was the Tatekawa River, and on the north side of the river was the straight Sakura Kaido. Travelers took this road to Nakagawa and crossed the river at "Sakasai Ferry". After crossing to the Chiba side, they could head a little north, avoiding the marshy areas, and go through Ichikawa to Sakura, Narita, and Boso. This road was the main road from Edo to the east. It is the Chiba Kaido today.

Let us take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting. First, at the top of the painting, quite far beyond, is Mt. Nokogiriyama. There were no tall buildings in those days, so it must have actually been visible from this location.

Below it, the villages of Sakai and Komatsugawa are depicted, surrounded by pine trees and Japanese zelkova trees. These are the villages on the Chiba side of the Nakagawa River, which is crossed by the Nakagawa River at "Sakasai Ferry".

The lower half of the painting shows the Nakagawa River in large scale. Since logistics was active in this area, a straw-covered transport boat is also floating in the river. There is a reed bed in the river, and five egrets are depicted there. This area used to be brackish water, with the tide rising from the ocean at high tide. This meant that many fish could be caught, and many little egrets and other waterfowl came to the area to take advantage of them. Because the river flows upside down, this area was called "Sakasai.

I actually went to this location.

The blue bridge in the photo is the current Sakasai Bridge, and "Sakasai Ferry" was located a little downstream of it.

Today, there is an information board at the side of Sakasai Bridge under the highway that states that "Sakasai Ferry" existed here.

This is what the view from the west side of "Sakasai Ferry" looks like. It is a bit dark, with the highway passing almost directly overhead.

A little further downstream, the river becomes more open, and the atmosphere is closer to that seen by Hiroshige. Both banks of the Nakagawa River are bordered by the metropolitan Oshima Komatsugawa Park, and the east and west sides of the park are connected by two pedestrian bridges.

With such a large piece of land, one would think that a large leisure facility with a huge capital would be built here, but in fact, this area has had major problems. Here is a map from the GSI with the passage of time.

First, please see the current situation on the orange map. The location of "Sakasai Ferry" is circled in red.

This map is from the early Meiji period, a few years after Hiroshige painted this area. You can see that the Chiba Kaido road extends along the Tatekawa River, and urbanization and residential development have begun to progress.

In the late Meiji period, we can see that the momentum of this trend increased and the area around the Nakagawa River was rapidly converted into a factory.

Around 1930, the maintenance of the large Arakawa River was coming to an end, and the number of factories along the Nakagawa River, where water was freely available, was increasing rapidly.

This is an aerial view of the current situation.

If you switch to an enlarged Applemap of the area around "Sakasai Ferry", you can see that a fairly large area of land was converted into Oshima Komatsugawa Park and an apartment complex.

In 1973, a large amount of hexavalent chromium tailings were discovered in the lower center of the photo at the site of the Oshima railcar inspection station of the Toei Shinjuku Line during a subway construction survey, and this became known throughout Japan as a soil contamination problem.

As you can see on the map, this area is an industrial area, and by the 1970s was the site where Nippon Chemical Industry had buried a large amount of chrome tailings. Since the tailings contained hexavalent chromium, it was treated to make it non-toxic and returned to the site, where it was turned into a park and opened in 1997.

Originally, in the 1970s, there was the fact that Nippon Chemical Industries in Edogawa and Koto wards had many health problems such as lung cancer and holes in the nose among its employees, and hexavalent chromium was then widely reported in the news as a pollutant in Japan.

Hexavalent chromium, which is used for chrome plating and other applications, must be detoxified by converting it to trivalent chromium, mainly by means of a reducing agent, when disposed of. The disposal of tailings by Koto Ward is said to have been completed in 2000, but a paper published in 2014 reported that seepage has occurred during heavy rain and snowfall.

Furthermore, even now, local council members have reported yellow water seeping from one part of the park to the water's edge on rainy days.

I inserted the current photo into Hiroshige's painting.

I wonder if Hiroshige would have never dreamed of such a situation. Since the situation is not conducive to canoeing, let alone playing with waterfowl, I have switched to a picture that is a little more Hiroshige-like.

It is said that "Japan has become affluent beyond the period of rapid economic growth," but even the negative legacy that remains cannot be detoxified, and even parks and metropolitan housing have been built on piles of land. We should think carefully about whether this is a sign of prosperity or not, and compare it with the landscape left by Hiroshige.

I visited my favorite "Meisho Edo hyakkei" (One hundred Famous Views of Edo) painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what those scenes look like today.

I visited my favorite "Meisho Edo hyakkei" (One hundred Famous Views of Edo) painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what those scenes look like today.

The "Sakasai no Watashi" (Sakasai Ferry) in No. 067 is a slightly elevated view of Sakasai Ferry, which was located where the current Komatsugawa line of the Metropolitan Expressway crosses the Nakagawa River. The Edo Shogunate did not build bridges over the river as much as possible at that time for defense purposes. This is one of many such bridges.

Please check the location of this bridge on Applemap. It was located about 7 km west of Edo Castle. Nowadays, the Arakawa River runs in a large north-south direction immediately to the east, but at that time, this Arakawa River did not exist, and the Nakagawa River flowed in a large meandering path as the largest river in this area.

As you can see if you zoom in on the map, south of the Komatsugawa Line of the Metropolitan Expressway is Shin-Ohashi Dori, and the Toei Subway Shinjuku Line runs almost parallel to it, and the station is located almost above ground from Higashi-Oshima Station, almost on the Nakagawa River.

The red gradient represents Hiroshige's viewpoint.

Beyond his line of sight is the metropolitan Oshima Komatsugawa Park, and to the north and south of it is a forest of metropolitan housing and other buildings.

If you switch Applemap to Street View, you can get a better idea of the size of the area.

To understand how they were able to create such a large park, please see the map from 1970. It is because both banks of the Nakagawa River at that time formed a large factory area, and later the Tokyo Metropolitan Government purchased this area and redeveloped it on a large scale.

Next, please take a look at the pictorial map of the time when Hiroshige painted this picture. The circled point is Nihonbashi. Travelers leaving Nihonbashi head north toward Odenmacho and enter the Oshu Kaido. From before the Kanda River, turn right and cross the Ryogoku Bridge.

To the south of the river was the Tatekawa River, and on the north side of the river was the straight Sakura Kaido. Travelers took this road to Nakagawa and crossed the river at "Sakasai Ferry". After crossing to the Chiba side, they could head a little north, avoiding the marshy areas, and go through Ichikawa to Sakura, Narita, and Boso. This road was the main road from Edo to the east. It is the Chiba Kaido today.

Let us take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting. First, at the top of the painting, quite far beyond, is Mt. Nokogiriyama. There were no tall buildings in those days, so it must have actually been visible from this location.

Below it, the villages of Sakai and Komatsugawa are depicted, surrounded by pine trees and Japanese zelkova trees. These are the villages on the Chiba side of the Nakagawa River, which is crossed by the Nakagawa River at "Sakasai Ferry".

The lower half of the painting shows the Nakagawa River in large scale. Since logistics was active in this area, a straw-covered transport boat is also floating in the river. There is a reed bed in the river, and five egrets are depicted there. This area used to be brackish water, with the tide rising from the ocean at high tide. This meant that many fish could be caught, and many little egrets and other waterfowl came to the area to take advantage of them. Because the river flows upside down, this area was called "Sakasai.

I actually went to this location.

The blue bridge in the photo is the current Sakasai Bridge, and "Sakasai Ferry" was located a little downstream of it.

Today, there is an information board at the side of Sakasai Bridge under the highway that states that "Sakasai Ferry" existed here.

This is what the view from the west side of "Sakasai Ferry" looks like. It is a bit dark, with the highway passing almost directly overhead.

A little further downstream, the river becomes more open, and the atmosphere is closer to that seen by Hiroshige. Both banks of the Nakagawa River are bordered by the metropolitan Oshima Komatsugawa Park, and the east and west sides of the park are connected by two pedestrian bridges.

With such a large piece of land, one would think that a large leisure facility with a huge capital would be built here, but in fact, this area has had major problems. Here is a map from the GSI with the passage of time.

First, please see the current situation on the orange map. The location of "Sakasai Ferry" is circled in red.

This map is from the early Meiji period, a few years after Hiroshige painted this area. You can see that the Chiba Kaido road extends along the Tatekawa River, and urbanization and residential development have begun to progress.

In the late Meiji period, we can see that the momentum of this trend increased and the area around the Nakagawa River was rapidly converted into a factory.

Around 1930, the maintenance of the large Arakawa River was coming to an end, and the number of factories along the Nakagawa River, where water was freely available, was increasing rapidly.

This is an aerial view of the current situation.

If you switch to an enlarged Applemap of the area around "Sakasai Ferry", you can see that a fairly large area of land was converted into Oshima Komatsugawa Park and an apartment complex.

In 1973, a large amount of hexavalent chromium tailings were discovered in the lower center of the photo at the site of the Oshima railcar inspection station of the Toei Shinjuku Line during a subway construction survey, and this became known throughout Japan as a soil contamination problem.

As you can see on the map, this area is an industrial area, and by the 1970s was the site where Nippon Chemical Industry had buried a large amount of chrome tailings. Since the tailings contained hexavalent chromium, it was treated to make it non-toxic and returned to the site, where it was turned into a park and opened in 1997.

Originally, in the 1970s, there was the fact that Nippon Chemical Industries in Edogawa and Koto wards had many health problems such as lung cancer and holes in the nose among its employees, and hexavalent chromium was then widely reported in the news as a pollutant in Japan.

Hexavalent chromium, which is used for chrome plating and other applications, must be detoxified by converting it to trivalent chromium, mainly by means of a reducing agent, when disposed of. The disposal of tailings by Koto Ward is said to have been completed in 2000, but a paper published in 2014 reported that seepage has occurred during heavy rain and snowfall.

Furthermore, even now, local council members have reported yellow water seeping from one part of the park to the water's edge on rainy days.

I inserted the current photo into Hiroshige's painting.

I wonder if Hiroshige would have never dreamed of such a situation. Since the situation is not conducive to canoeing, let alone playing with waterfowl, I have switched to a picture that is a little more Hiroshige-like.

It is said that "Japan has become affluent beyond the period of rapid economic growth," but even the negative legacy that remains cannot be detoxified, and even parks and metropolitan housing have been built on piles of land. We should think carefully about whether this is a sign of prosperity or not, and compare it with the landscape left by Hiroshige.

I visited my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like today.

I visited my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like today.

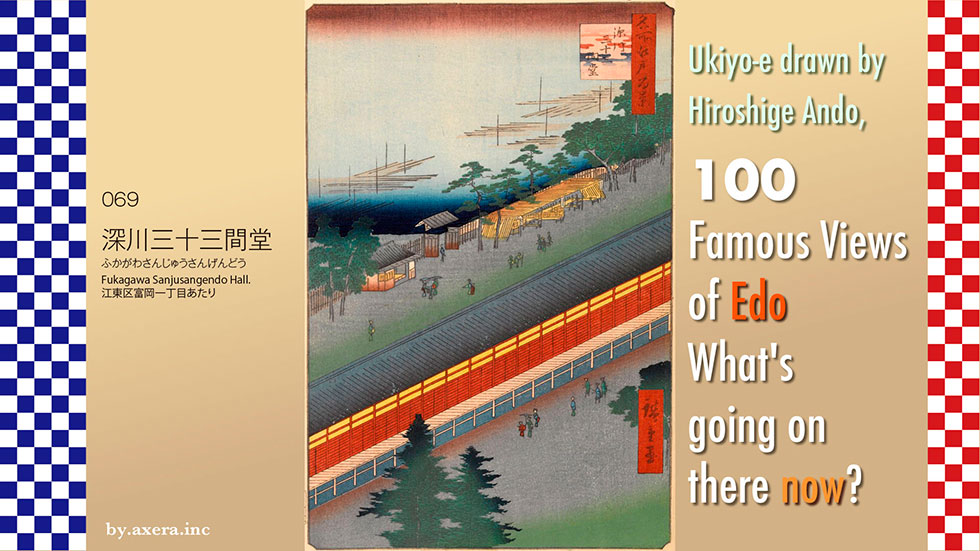

Fukagawa Sanjusangendo Hall" (069) is a bird's-eye view of a hall located a little east of Tomioka Hachiman Shrine in Monzennaka-cho.

First, please see the map. Tomioka Hachimangu Shrine was located a little more than 1 ri, or about 4.5 km, east-southeast of the Edo Castle keep, and this hall was on the east side of the shrine.

Even when covered by a pictorial map of the time, the notation is written in large red letters.

Please see the GSI map, which is a little more enlarged. If you put the map of the early Meiji period on top of it, you will see that Sanjusangendo Hall was a rather large building.

If you zoom in a little more and use the current Applemap, you can see that Sanjusangendo Hall was located on Kotohira-dori.

I have used a purple gradation to represent Hiroshige's point of view.

At that time, the practice of "through-the-arrow" archery was popular in the main hall of Rengeoin Temple, or Sanjusangendo, in Higashiyama, Kyoto, as part of the archery training of samurai. In November 1642, Bingo, an Edo-style archer, built a hall modeled after Sanjusangendo in Asakusa, next to Higashi Honganji Temple, in order to practice the same in Edo. The building was later destroyed by fire in 1698, and was rebuilt in 1701 on the east side of the present Tomioka Hachiman Shrine.

The title of this painting is "Edo Fukagawa Sanjusangen-do no tsuzu" (Edo Tomigagawa Sanjusangen-do no tsuzu), but the Higashiyama-like background and the tall building in the background, which is probably the Great Buddha Hall of Hokoji Temple, suggest that the model for this painting is Sanjusangen-do in Higashiyama, Kyoto.

The title of this painting is "Edo Fukagawa Sanjusangendo Hall Painting," but the Higashiyama-like background and the tall building in the background, which is probably the Great Buddha Hall of Hokoji Temple, suggest that it was modeled after the Sanjusangen-do Hall in Higashiyama, Kyoto.

Sanjusangendo is 66 ken (120 meters) long from north to south, and the west side of the hall was the venue for the "through-the-arrow" game. It is said that there were different types of arrow games such as distance, time, and number of arrows, but the basic game was to see how many arrows could be shot in rapid succession as quickly as possible. The record-holder was given the title of "the best in Edo," and his name and the number of arrows he shot were written on an ema (votive tablet), which was displayed in the hall.

Perhaps as a remnant of this tradition, the name of the elementary school behind Hachimangu Shrine has been changed to Koto Ward Kazuya "Many arrows" Elementary School.

In this Hiroshige's Edo Meisho, the picture is seen over the Sanjusangen moat on the east side, now the Heikyu River. In the foreground is a lumberyard, lined with lumberyards, and beyond the houses on the left is a tideland. The pillar-like structure on the right is a sail post of a large ship in Tsukuda Minato, and the back of the picture is Edo Bay and the direction of Shinagawa.

The "through-the-arrow" ceremony took place behind the scenes.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting. The upper part of the painting, at the back, is the Sanjusangen moat, now the Heikyu River, which also served as a lumberyard. Although the opposite bank is omitted in the painting, the actual moat was only a few meters long. Along its shores, there were hanging teahouses, etc. If you go to the far right, you will hit the Sanjusangen moat, which turns to the right, and beyond that, via the lumberyard, you will reach Edo Bay, which was still a tidal flat. Going left along the moat, you will pass the Kamekyu Bridge and reach Joshinji Temple in Hirano.

The Sanjusangendo Hall, which crosses diagonally, had arrows shot from an open space in the left front and a target at the far right end. You can see some onlookers looking at the arrow through it.

I actually went to this place. Today, Kotohira Street runs right around where the hall used to stand, and only the monument remains.

The south side goes via Eitai Street, crossing the Oyoko River in the direction of Botan 3-chome. But now, the ocean is still much further away.

To the north, via the Komatsugawa Line of the Metropolitan Expressway, one can exit toward Fuyuki and Hirano. On the corner of the road leading to Hachimangu Shrine, Kamaro, famous for its steaks, is still in business.

I actually tried to fit the current condition into the Hiroshige picture. But it turned out to be just a picture of an apartment building, so I relied on Applemap's Street View.

But it still turned out to be a picture that looks a little bit like the one in the street view.

This painting by Hiroshige was issued in August 1857. However, records show that two-thirds of Sanjusangendo Hall was destroyed in the Great Ansei Earthquake that occurred a year and a half earlier. Furthermore, in August 1856, a massive typhoon hit the area, and the Fukagawa area suffered considerable damage from the storm surge. There is no way that this hall, so close to the sea, could have survived.

According to records, Sanjusangendo Hall was repaired from November 1860 to June 1862. At that time, Hiroshige had already passed away.

In fact, before the publication of this painting, Hiroshige published a picture of almost the same composition in the picture book Edo Souvenir. Apparently, Hiroshige was depicting Sanjusangendo Hall from a bird's eye view from heaven.

I actually visited and saw what those scenes look like today in my favorite "One hundred Famous Views of Edo" (Meisho Edo hyakkei) painted by Hiroshige Ando.

I actually visited and saw what those scenes look like today in my favorite "One hundred Famous Views of Edo" (Meisho Edo hyakkei) painted by Hiroshige Ando.

Nakagawa River Mouth at 070 depicts a waterway where the Nakagawa, Onagi, and Shinkawa Rivers cross each other.

First of all, please look at the map by the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (GSI). The area about 7 km east of Tokyo Station, where the Onagi River and the old Nakagawa River intersect, will be the setting for this project. I have circled it in red. The large vertical Arakawa River shown on modern maps did not exist at that time.

I put this over a map from the early Meiji period, a few years after Hiroshige painted this picture. As you can see from this map, the area where the Tozai subway line runs today is on the coastline, and when Ieyasu Tokugawa came to Edo, the sea and mud flats were much deeper into the city.

Water transportation played a key role in the transportation of goods during the Edo period, and around 1590, Tokugawa Ieyasu, who settled in Edo Castle, turned his attention to the Gyotoku salt fields in order to secure salt, a strategic commodity. However, the northern part of Edo Bay from Gyotoku to Edo Minato was covered with sandbars and shoals that often ran ships aground, forcing them to make large offshore detours. Even if a detour was made offshore, it would still be dangerous if the sea became rough, so Onagi Shirobei was ordered to open a canal to Gyotoku. This was the Onagi River, which was widened over time and became an important waterway.

I enlarged the map a little more and put a map of the same scale from the early Meiji period on top of it. I put a red gradient on the area where Hiroshige's point of view would have been.

Please see a more extensive map. After the completion of the Tonegawa River eastward shift project that started in the early Edo period (1603-1867), goods for eastbound shipping did not bypass the Boso Peninsula, but instead traveled from Choshi up the safe Tonegawa River to Sekiyado, then entered Edo via the Edogawa, Shinkawa, and Onagigawa Rivers.

You can clearly see that this location was a key point for water transportation. Today, it is like the Ryogoku Junction of the Metropolitan Expressway.

Let's actually take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

Below the dark blue gradient, the mountains of Chiba can be seen through the red hazy clouds. It does not seem to be Mt. Nokogiriyama in terms of direction.

Toward the back of the screen is the Shinkawa River. Flowing to the left and right is the Nakagawa River, and down in the foreground is the Onagigawa River. There are two boats passing by and several Takase-boats with mushiro on their sides moored on the Shinkawa River.

The rafts floating in the Nakagawa River symbolize the thriving lumber distribution industry. In addition, two fishing boats are depicted here, as the area is close to the sea and brackish water, where fish are plentiful. In fact, it seems that sea bass, a favorite of Edo citizens, was often caught.

In the foreground, two 24-passenger passenger boats called nagatosen, which traveled between Edo and Gyotoku, pass each other on the Onagigawa River. By this time, the transportation of humans and other daily commodities had replaced salt as the main form of water transportation on the Onagigawa River. In the 5th year of the Kanbun Era, each passenger was charged 17 mon, which would be a little over 200 yen in today's sense. Citizens called it "Gyotoku-bune," or "Gyotoku boat," and it was a popular form of daily transportation.

On the left side below the painting, there was a "Gobansho," a water barrier that controlled and supervised boats, although it is not depicted in the painting. Two travelers walking along the banks of the Onagigawa River are depicted on the lower side of the painting, which is the direction these travelers are heading.

Before this painting, Hiroshige painted a picture from the "Gobanjo" side in his picture book "Edo Souvenirs. The building with the flag on the lower right is the one shown in this painting. The commentary on the painting, translated into modern Japanese, reads as follows.

The Nakagawa River is located between the Sumidagawa River and the Tonegawa River, so it is called the Nakagawa River. There are many fish here, and from spring to fall, net boats and fishing boats are constantly visiting the area, making it a place of amusement for many people."

Furthermore, Hiroshige painted a more straightforward and materialistic "Gobanjo" around the time of the Tempo era.

This "Gobanjo" was usually called Funabansho, and was a barrier that strictly monitored people entering and leaving Edo, as typified by the phrase "Incoming guns and outgoing women" (Edo Shogunate policing provisions for maintaining public order). However, as the peaceful period of Edo continued for a long time, it seems that by the time Hiroshige painted this picture, it had changed to a level where people would pass through with a light touch.

I actually went to this location. This is a shot taken from the top of the Bansho Bridge, the closest bridge to the Nakagawa. The Shinkawa River, which used to run through to the other side, is now out of sight. The Arakawa River, created by the Arakawa Spillway Project, flows in both directions, dividing the Shinkawa River, and the Oshima Komatsugawa Park and Kaze no Hiroba, built on the right bank of the Arakawa River, can be seen standing in the way.

Only a small monument remains after the Funabansho (boat guard station.)

The Onagigawa River still runs almost in a straight line to the Sumidagawa River.

About 200 meters north of here, the Koto-ku Boat Guard Station Museum was built.

Please see the photo taken from the same location in "Contrasting Edo 100 Views of Now and Then" published in 1919. You can see that the Arakawa River drainage canal has not yet been constructed and is connected to the Shinkawa River. You can see that factories and other facilities are beginning to be built on the Shinkawa side at this time.

The Onagigawa River, created for the purpose of transporting strategic goods, later became an important logistics route supporting the citizens of Edo, and with just one word to the initially very strict ship guard station, boats would pass by laughing. I believe that Hiroshige depicted such "remaining peaceful atmosphere" of Nakakawaguchi.

Just before he painted this picture, the unseen black ships had arrived, the town of Edo had been destroyed by the Ansei earthquake, and people's minds were covered with the Emperor's exclusionist sentiment, making it difficult to see the future.

Well, how about now? I actually tried to fit the current situation into Hiroshige's painting.

This is a peaceful landscape. However, compared to the tranquil landscape of peace itself that Hiroshige depicted, I feel much more uneasy about the future.

Now, conflicts are being fought on a global scale, hegemony is rampant, and no one is able to stop it. Don't you feel that something else is quietly coming over the forcibly created embankment of the Arakawa River in the front of the photo?