I visited my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like today.

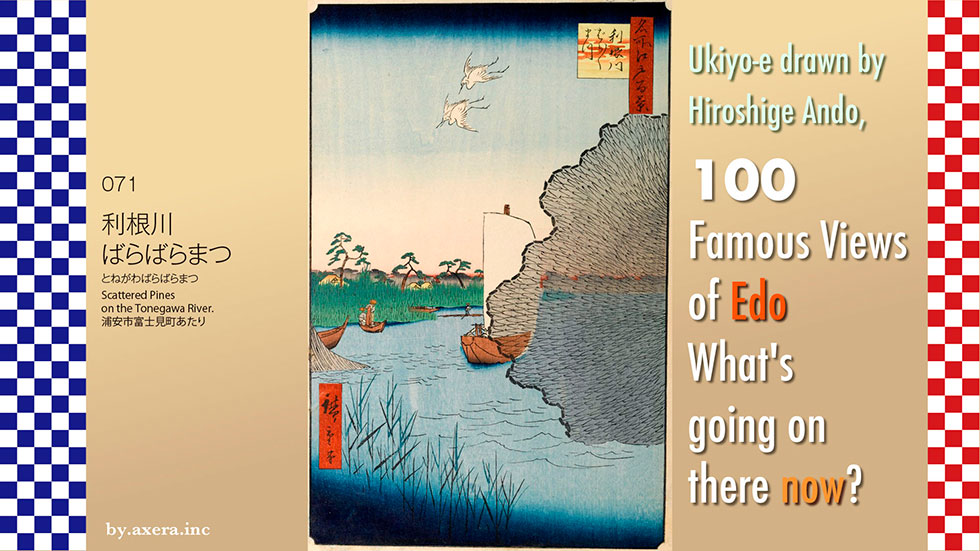

Scattered Pines on the Tonegawa River (071) depicts a scene of the old Tonegawa River over a cast net thrown by a fisherman. However, there are various theories as to where this painting was painted, and a definitive location is still unknown.

First, let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

Under a blue gradient sky, two little egrets are flying with their necks bent in a "tsu" shape. They look as if they are trying to catch a piece of the fisherman's fish. Just below them, in the center of the image, are a scattered pine tree and several houses. The "scattered pine trees" is not a proper noun, but means that the pine trees are planted in a scattered manner.

In the center of the image, a benzai-sen boat floats, which can be assumed to be a boat that came up the Tonegawa River from Choshi and came down from Sekiyado. It can be seen that the Tonegawa River was the most important route for waterborne logistics.

To the left, two fishermen's boats are casting nets. On the right side of the picture, a cast net that has just been thrown is spread out. Since the fishermen are using cast nets, it is assumed that the fishermen depicted are river fishermen who catch carp, crucian carp, dace, and other fish. However, there is also a theory that the fishermen are white fish fishermen who were permitted by the shogunate to use cast nets only near the mouth of the Nakagawa River, even though white fish fishermen normally used four-handed nets.

In any case, it is amazing that the carver carved each and every line of the net of the spreading cast net. Moreover, if you look closely, you can see that the entire netting is also covered with light black ink.

The river is a marshy area with reeds growing in it, and the river is thought to be the Tone River, as the title suggests.

Now, to see where this drawing depicts, please first look at the current GSI map. I will add the main lines and stations to this.

Let us now add to this a relatively accurate map from the early Meiji period, a few years after the painting was made. The area around the Tozai subway line was still the sea, and the rivers flowing vertically were, from left to right, the Sumidagawa River, the Nakagawa River, and the Edogawa River. However, there was a time when both the Nakagawa and Edogawa Rivers were also called the Tonegawa River. This complicates location identification. For now, three promising candidate locations are shown on this map, circled by red dotted lines.

Next, using a slightly larger map, we will roughly describe the Shogunate's projects that led to the two rivers being called the Tone River. This is also covered with a map from the early Meiji period.

First of all, when Tokugawa Ieyasu established the Edo shogunate, the Shingashigawa, Arakawa, and Tonegawa Rivers flowed into Edo Bay, although they changed their course many times. In other words, rainfall in Saitama, rainfall in Chichibu, and rainfall on the Joetsu border all flowed into Edo Bay, causing the city of Edo to suffer from flood damage.

Therefore, the Shogunate gradually shifted the water of the Tonegawa River to the east while diverting it. In the process, the Tonegawa River became the Nakagawa River for a time, and then the Edogawa River for a time. Finally, the main stream of the Tonegawa River was renamed to flow into Choshi as it does today, adding the Kinugawa and Kokaigawa Rivers. This is a very rough description, but this is the Tonegawa River eastward shift project. So both the Edo and Nakagawa Rivers were "Tonegawa Rivers. However, around the end of the Edo period, when Hiroshige lived in Japan, the Tonegawa River was often referred to as the Edogawa River.

Before painting this picture, Hiroshige painted the same Scattered Pines on the Tonegawa River in his picture book "Edo Souvenir. In his commentary, he wrote, "The Tonegawa River is the largest river in Bando(Kanto region), and is also known as Bando-Taro. This means that the pine trees were planted in pieces along the banks of the Edogawa River.

In addition, the geographical magazines "Edo Kanoko" and "Edo Sunago" also mention a Scattered Pines that was located in the Nakagawa River. However, the specific names of the places where they were located are not given. According to a recent book written by a famous Ukiyoe researcher, an old man who saw the same scene near the mouth of the Edogawa River has written about it, and it has attracted much attention.

In 1919, the book "Now Edo Hyakkei (100 Famous Views of Edo from Now to the Past)" was published, which contains photographs of places where 100 Famous Views of Edo was drawn, and Scattered Pines is also included in the book. In the book, the Scattered Pines is shown in a photo, and it says, "You can see the actual view if you go 15-6 chou(1.5km) to the south from Urayasu.

The place we went was Fujimi-cho, Urayasu City, from where we looked at the other side of the river and upstream.

Nowadays, motorboats, not benzai boats, come and go. Of course, there are no pine trees.

Myokenjima is on the other side of the bridge at the far right. This is the opposite shore in Hiroshige's painting, as claimed by some researchers.

It is shown in red gradation on the map.

This is a photo of another candidate, looking north from the embankment of the old Imaibashi Bridge. Again, no pine trees exist here.

This is a photo looking in the direction of Imai Bridge over the old Edogawa River. Myoken Island is located far beyond this bridge.

Let me insert into Hiroshige's painting a photograph from Fujimi-cho, Urayasu City, inferred from the "Now Edo Hyakkei (100 Famous Views of Edo from Now to the Past)".

Imagine a pine tree just planted sparsely beyond the light, the river cormorants, and the tall foamy grass. Perhaps this is a different place.

The Nakagawa River was connected to the Tonegawa River at Gongendo, about 1.5 km southeast of the current Kurihashi Station on the JR Tohoku Line, but is not connected now. The Edogawa River is connected to the Tonegawa River at Sekiyado, about 5 km further on. Here, one can still see the branching part of the Tonegawa and Edogawa Rivers.

This photo is a view toward the Joetsu border from the Sekiyado junction where the Tonegawa and Edogawa Rivers part in late autumn. You can see snow-capped mountains in the distance.

The Tonegawa River eastward shift project to protect Edo from flood damage began in the 7th year of the Genna Era (1621). This was a surprise, but it necessitated the construction of revetments along the Sumidagawa River as well as the Nakagawa and Edogawa Rivers. Many trees were planted to strengthen the levees for this purpose. Cherry blossoms were the basic type of tree for this planting, and pine trees were also used in large numbers near the mouths of the rivers. This may be the reason why pine trees always appear in ukiyoe paintings that depict waterfront areas. So, there may have been many more places with scattered pine trees.

I actually visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando, one of my favorite artists, to see how the scene looks today.

I actually visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando, one of my favorite artists, to see how the scene looks today.

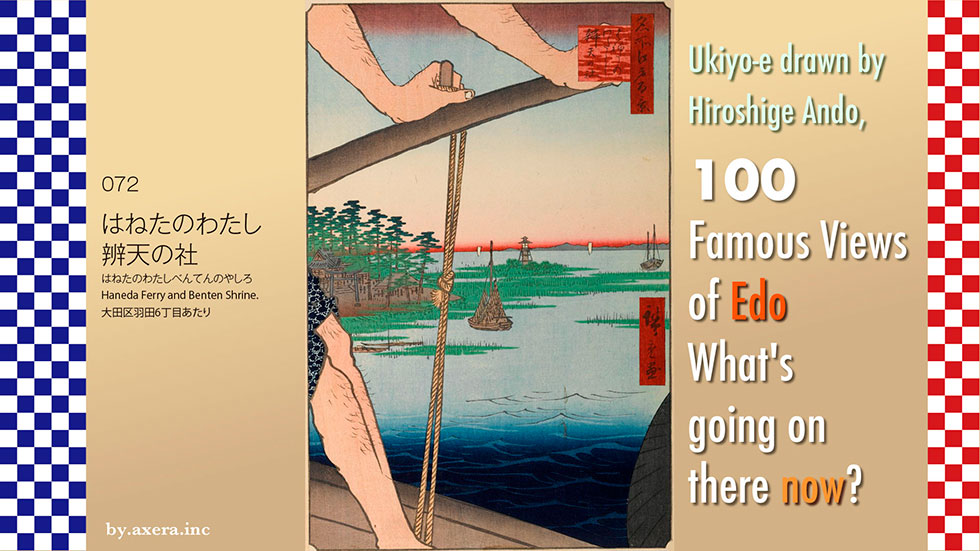

The "Haneda Ferry and Benten Shrine" in 072 is a view looking toward Haneda Benzaiten over the boatman of a ferryboat.

First, to see where this place is located, please look at Applemap. It is about 17 km south of Edo Castle.

It's around the southern entrance of Haneda Airport.

I further enlarged the image and added a red gradient at the location where Hiroshige's viewpoint would have been. This is the view from the foot of Benten Bridge over the Ebitori River in Haneda 6-chome.

Let's actually take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting. The first thing that catches the eye is the hairy hand of the boatman in the upper part of the picture. Beyond the coastline, Uraga and the mountains of Boso can be seen overlapping each other, and in the Edo Bay, there are two large Benzai boats and another one in the near view. The nightlight between the two boats is different from the one in Benzaiten shrine, which was hurriedly built offshore for maritime defense after the arrival of the black ships from USA.

On the left, Haneda Benzaiten Shrine is depicted surrounded by a pine forest. This was also known as Kanameshima Benzaiten, because it was located on Kanameshima-island in the "Ohgigahama," a state made of sand carried by the Tamagawa River. It was a familiar Benten deity that was deeply believed in by the local fishermen, but Hiroshige seems to have drawn it much closer in composition than it actually was at a greater distance.

One boat with a drying net and two other small boats are depicted beside Benzaiten Shrine, surrounded by a reed field. In fact, the area near the mouth of the Tamagawa River seems to have been a sandy marshland with vast reed beds.

The waterside beneath the boatman's feet was the Tamagawa River, and this area was called "Rokugo River" at that time. This ferry was located at the foot of what is now Benten-bashi Bridge, from where the boatmen crossed to the Kawasaki side of the river.

Here are three of Hiroshige's picture book Edo Souvenirs. Travelers coming from Edo on the Tokaido usually crossed the Tamagawa River at Rokugo Ferry.

However, there was another way, coming from Omori on the way there to Haneda on Haneda Road, and going from Haneda Ferry to Daishi Gawara. In this case, however, Haneda Ferry, also known as "Rokuzeemon Ferry", refers to the ferry that was located upstream from the Haneda Ferry painted by Hiroshige, around what is now the Daishi Bridge. The ferry operated by the boatman depicted by Hiroshige was also known as "Daishi Gawahara Ferry", and the main purpose of its travelers was to visit Kobo Daishi's Heigen Temple, or Kawasaki Daishi, going via Anamori Inari shrine and Haneda's Benzaiten shrine.

Furthermore, Hiroshige painted a large image of Haneda Benzaiten shrine in his eight views of the Edo suburbs, under the title Haneda Rakugan.

On the east side of Haneda Village is the Ebigawa River, over which there was a bridge made of old ship's bottom plates. After crossing that bridge, a narrow path along a rough beach with only reeds and grass led to the Haneda Forest, in which the Haneda Benzaiten shrine stood facing south.

At first, it was built with a stone wall with a sutra written on it in Kanameshima Island, which was a state away from the land, but with the accumulation of sand in the Tamagawa River and reclamation by fishermen, it seems to have become possible to go there by land.

This Haneda Benzaiten is said to have originated when fishermen in Haneda scooped up and enshrined in a net a jewel that had drifted down from the mountain where Kobo Daishi had founded the temple.

According to the commentary on the Edo souvenir painting, the principal image is said to be the same body as that of Benzaiten on Enoshima Island, Kanagawa Prefecture, and to have been created by Kobo Daishi, and was recommended by Kaiyo Shonin in 1711.

A document written in 1818 states, "The Benten shrine stood on a high stone stairway, and a night-light stood in the garden of the monk's quarters to the east. The fact that so much documentation has survived suggests that it must have been a place of great scenic beauty, with a strong belief among fishermen.

Now, I actually went to this location. However, only the Benten Bridge is visible.

A little closer to the Tamagawa River from the Benten Bridge, the view becomes clearer. The Benten shrine depicted in the painting was located behind the red torii gate, where the embankment from the right meets it, but has now been moved. The building behind it is Haneda Airport Terminal 3. The tall bridge on the right is the new "Tamagawa River Sky Bridge.

This photo is taken from the Sky Bridge, looking in the direction of Hiroshige's viewpoint. In front is the confluence of the Ebitorigawa and Tamagawa Rivers, which is the viewpoint. The red torii gate can be seen on the right. The Benten shrine was located on the right side, where the red light can be seen.

I turned the camera toward Kawasaki.

This is the Benten shrine that was relocated to the former Hunters' Town. It looks a bit lonely now.

Now please check the GSI's map of Benten shrine and Hiroshige's viewpoint.

Haneda had been a fishing village since the Middle Ages, but in the late Edo period, the area facing the Tamagawa River was so rich in fish and shellfish that it became a fishing town, called Haneda Hunters' Town, and was very busy.

The name "Haneda" has nothing to do with the airfield, but with the shape of the land divided into two parts by the Ebitorigawa River, which looks like a bird spreading its wings when seen from the sea.

The east side of the Ebitorigawa River, called Kanameshima, where the Benten shrine was located, was reclaimed and cultivated since the Temmei era (around the 1780s), led by Yagoemon Suzuki, a master farmer in the Haneda Hunters' Town, and was called Suzuki Shinden(newly developed rice field) at this time.

In 1913, the Keihin Electric Railway (now the Keikyu Railway) was extended to Anamori Inari station, improving transportation access and further developing the area.

In 1931, Haneda Airpoat was opened on the north side of Suzuki Shinden, and the name Haneda became known throughout Japan in both name and reality.

However, one day in August 1945, the Allied Forces suddenly decided to confiscate and expand the airport, and approximately 3,000 residents from 1,200 households east of the Ebitorigawa River were forcibly evicted from the area within 48 hours.

Please take a look at this aerial photo from 1947. You can see that the parts of Haneda Anamori-cho, Haneda Edomi-cho, and Haneda Suzuki-machi that used to be inhabited towns have all been destroyed.

Here is an aerial photo that shows a little more of the surroundings.

In 1952, the airport was returned to Japan from the Allied Forces and became Haneda International Airport, the gateway to Japan's skies. Later, it was demolished to make way for the relocation and expansion of the airport, and this is what it looks like now. However, this is unquestionably the place where about 3,000 people actually lived until 1945.

This is an aerial photo taken when the airport was returned and became the former Haneda International Airport.

This is an aerial view of the current Haneda Airport, which has been further expanded and relocated and now has three terminals.

This is a view of the area around the former Haneda International Airport from the Tamagawa Sky Bridge. Today, there is not a single building, including the Benten shrine, Anamori Inari shrine, private houses, or any other building where life can be seen.

The current view is actually inset into Hiroshige's painting.

This red torii gate was erected at the Anamori Inari Shrine in the early Showa period. After the war, the U.S. military occupation forces demolished all the houses on the east side of the Ebitorigawa River, but only this torii gate was spared from demolition and remained here after being moved twice. When Hiroshige painted this picture here, he probably never imagined that such a sad event would take place here later.

Today, the torii gate stands as a shrine for world peace, with the word "peace" engraved on the forehead and the Peace Bell hanging below it.

I visited my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like today.

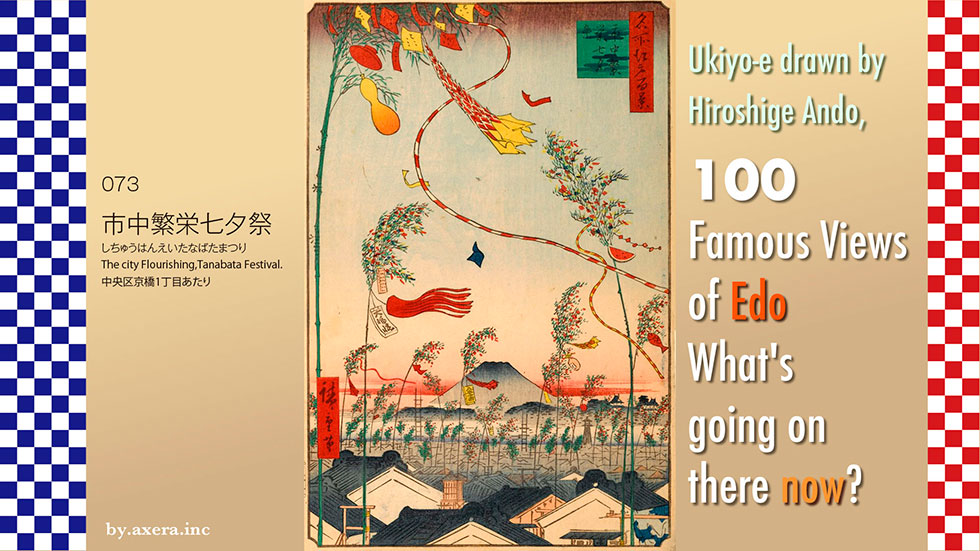

073 "The city Flourishing,Tanabata Festival" depicts the scenery of the Tanabata Festival in Edo as seen from Kyobashi area.

The point where Hiroshige painted this picture is said to be balconies of his house. At that time, Hiroshige lived in a place called Oga-cho, which is around Kyobashi 1-chome today. Please check its location on the map.

When viewed from the Edo Castle keep, it is just behind the current Tokyo Station, about 500 meters east-northeast of the station.

As you can see if you zoom in on the map a little more, the alley is almost directly south of the former Bridgestone headquarters, now the Artizon Museum of Art. Here is the location of Hiroshige's viewpoint, indicated by the red gradient.

Here is a map of the time. You can see that the current Metropolitan Expressway is a moat, and that Yaesu Street leading to Tokyo Station was also partially moat.

Although Tanabata is now regarded as a summer festival for Orihime and Hikoboshi, it was originally one of the seasonal festivals called Sekku, which originated from the Chinese theory of Yin-Yang and the five elements. Various seasonal festivals existed throughout the year, and the Edo shogunate designated five of them as official events and holidays.

January 7, Jinshitsu, is the day of the seven herbs festival, and the seven herbs gruel is served on the day of the seventh herb.

March 3, Joushi, is the Peach Festival or Hina Matsuri (Girls' Festival), during which water chestnuts and white sake are served.

May 5, Tango is Dragon Boat Festival, is the festival of iris, and is celebrated with iris sake and iris baths.

Kashiwa-mochi (rice cakes with sweetened oak leaves) are eaten in the Kanto region, and chimaki (rice cake wrapped in a thin layer of rice flour) in Kansai.

July 7,Shichiseki is a bamboo grass festival, commonly called Tanabata (Star Festival) or Hoshimatsuri (Star Festival), where somen noodles were eaten in hopes of improving one's sewing skills. This may be due to the influence of Orihime, the goddess of weaving.

September 9, Choyo is the festival of chrysanthemums, and we had sake with chrysanthemums floating on it, etc.

However, since these festivals were held according to the lunar calendar, they were about one month later than the current calendar. Tanabata is held on or around August 15, so it seems that the common people of Edo were aware that it was not a summer festival, but a festival held at the end of summer or early autumn.

Now, please take a look at a picture of Tanabata left in Ukiyoe of the time.

When Tanabata Festival approached, bamboo grass vendors appeared in Edo town, and it was fixed to be put up on balconies or in gardens on the evening of July 6. Regardless of status or wealth, Edo citizens enjoyed preparing for the event by making decorations and hanging them on the bamboo branches before the event.

As Tanabata became popular among the general public, writing wishes on tanzaku (paper strips of paper) seems to have started around the Edo period. It was considered a good idea to hang not only tanzaku, but also other decorations with their own significance, and to raise the bamboo branch as high as possible.

The "blowing streamers" represented the weaving threads of the weaver and were also meant to ward off evil.

Kamiko, kimonos made of Japanese paper, were used to pray for the improvement of sewing skills and that people would not have trouble finding things to wear.

Net ornaments were used to pray for a good catch of fish, abacus and Daifuku-cho for prosperous business, writing brushes and inkstones for good penmanship, gourds for good health, and watermelons for a bountiful harvest.

The bamboos that had fluttered across the Edo sky were cleaned up on July 7, the day of the Tanabata Festival. It is truly a star festival. It is said that both the offerings and the bamboo branches were washed into the river or the sea to purify and wipe out impurities, which is related to the custom of the Bon Festival.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

First, at the top, the sky is wide open, and many Tanabata decorations hung on bamboo branches are depicted. Tanzakus, streamers, gourds, cups, and other decorations are hung so that wishes can reach the sky.

If you look down to the bottom, you will see that the town is made up of bamboo grass as if it were a forest. Fuji in the distance is also drawn quite large, perhaps for balance. The grove-like structures seen on the lower side of Mt. Fuji are Kojimachi and Kudan Hill, and Edo Castle is also depicted in a small size on the right side.

The small fire watchtower depicted below Edo Castle is the fire watchtower of Yayosu-gashi, where Hiroshige, a former firefighter's assistant, worked.

This Yayosu-gashi is the original name of the current Yaesu area, but in the Edo period, it referred to the area along the inner moat of Edo Castle from the Wadakura-mon gate to the Babasakimon gate area, in other words, the area around today's Marunouchi. It is said to have originated from Jan Joosten, a Dutch navigator who drifted ashore in 1600.

In front of the numerous bamboo branches and houses are several large white warehouses, which are said to be the famous Minami-Denma-cho 3-chome merchant houses in Edo, known as "Kyobashi no ShihoGura" at the time. The house in which Hiroshige lived escaped the spread of fire thanks to this storehouse during the Great Ansei Earthquake. However, it seems that Hiroshige intentionally miswrote the actual warehouse, as it appears to have been black in color.

I actually went to this location.

Looking up from Hiroshige's viewpoint, I saw a large crane quietly moving in front of me. This is where the Toda Corporation headquarters building is now under construction. On the Chuo Dori side of the street is the Mitsui Garden Hotel, and beyond it rises the new Midtown Yaesu in front of Tokyo Station. The Artison Museum is slightly visible on the right.

The actual viewpoint of Hiroshige is a little further to the left in the direction of Kyobashi Edogran, but nothing can be seen from here.

If you shift a little to the south, you can barely see as far as the central avenue, but at lower elevations you can't see anything.

I tried to fit the actual scenery into Hiroshige's painting.

The painting gives the impression of many bamboo grass turned into one giant crane.

So, I created a modern Tanabata Festival by combining Google Street View and a picture of Mt. Fuji in summer without snow. What do you think? Does it look like a peaceful picture?

It is recorded that Hiroshige spent most of his days on the second floor of his house, painting and doing other things. This means that he spent most of his time looking at this view every day of his life.

Although Hiroshige's house was lucky to escape a similar fire, the city of Edo was devastated by the Great Ansei Earthquake. A year and a half later, on the evening of July 6, Hiroshige saw the Tanabata decorations high in the sky dancing from the second floor of his house. He must have been very happy. He must have been thrilled that peace had finally returned to Edo.

However, the times were about to take an unexpected turn.

I visited my favorite "Meisho Edo hyakkei" (One hundred Famous Views of Edo) painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what those scenes look like today.

I visited my favorite "Meisho Edo hyakkei" (One hundred Famous Views of Edo) painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what those scenes look like today.

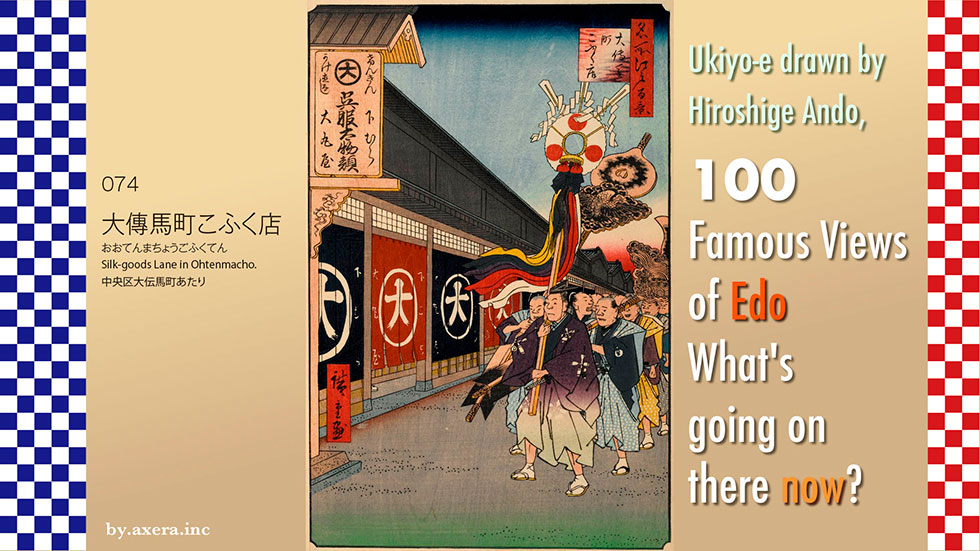

The "Silk-goods Lane in Ohtenmacho" in 074 depicts a group of Toryo-okuri (Ceremony to send off the master carpenter) passing in front of Daimaruya, which was located on the Oshu Kaido Road.

First, please check the map to see where this location is depicted.

It is roughly east of Edo Castle, almost two blocks east of the current Tokyo Metro Kodenmacho station.

The road along which the group of Toryo-okuri is walking is now called O-htenmacho Honcho-dori, which at that time was the Oshu Kaido, one of the five main Kaido in Edo.

At that time, the actual name of the place was "Tori-Hatago-cho," but Daimaru used the name Ohtenmacho, which had name value, and called it Ohtenmacho 3-chome.

I have represented Hiroshige's viewpoint with a red gradation and covered it with a pictorial map of the time. If you look closely, you will see that the southern back street is marked as Daimaru Shinmichi (Daimaru New Street). You can see how Daimaru had a great influence on the area.

Now let's take a closer look at the actual painting.

The building on the left is the Daimaruya drapery store, and the procession walking to the right of it is the Toryo-okuri. It looks like some samurai family has just finished a ridgepole-raising ceremony and is approaching Daimaruya just before this.

In those days, after the ridgepole raising ceremony, a procession was held from the construction site to the home of the ridgepole beams. The "Heigushi" carried by the leader of the procession was a festive pillar decorated during the ridgepole raising ceremony, and was about 3 meters long. A mirror, a Hinomaru fan, and a gohei (staff of the rising sun) were attached to the top of the pillar, which was then decorated with a comb, a hair ornament called a "Tegara", a kamoji (a hair piece used in those days), and a five-colored cloth. It is said that these hair-tie tools are remnants of the ancient custom of using young women as human pillars.

Later, a large arrow is carried by a pair of cranes and turtles, both symbols of good luck. These arrows were used as arrows to ward off evil spirits at the devil's gate at construction sites.

In fact, this painting was painted as an advertisement for sales promotion.

In addition to this, Hiroshige painted several other ukiyoe for advertisements that would have been commissioned for the Edo 100 series. The cost of these advertisements was a valuable source of income for the publisher, Uoei.

Let us follow them in chronological order.

8 view Suruga-cho

Published September 1856

Echigoya

Present Mitsukoshi Department Store, Nihonbashi

It is now a department store operated by Isetan Mitsukoshi under the umbrella of Isetan Mitsukoshi Holdings Ltd.

13view Shitaya Hirokoji

Published September 1856

Ito-Matsuzakaya

Present Matsuzakaya Department Store, Ueno

Currently, the department store is operated by Daimaru Matsuzakaya Department Store, a member of the J. Front Retailing Group, which merged with Daimaru.

7view Momendana Cotton-goods Lane in Ohtenma-cho

Published September 1858

Tabaytaya, Masuya, Shimaya

Current Nomura Real Estate Nihonbashi Honcho Bldg.

This is now an office building and all three stores are believed to be closed.

74view Silk-goods Lane in Ohtenmacho

Published July 1858

Daimaruya

Currently an office building

It merged with Matsuzakaya and became a department store operated by Daimaru Matsuzakaya Department Store, a member of the J. Front Retailing Group, with its main store in Shinsaibashi, Osaka. Currently, there is a Daimaru Tokyo store in Yaesu, Tokyo Station, adjacent to the station.

44view View of Nihonbashi Tori 1-chome Street

Published August 1858

Shirokiya

Current COREDO Nihonbashi

In 1956, it became part of Tokyu Corporation, and after the Tokyu Department Store Nihonbashi, this location is now the COREDO Nihonbashi, which also serves as an office building.

Hiroshige also depicted Daimaru in his Edo Meisho.

Daimaru was originally founded in 1717 when Shimomura Hikoemon Shokei opened a secondhand clothing business, Daimonjiya, in his birthplace in Fushimi, Kyoto.

Later, he opened stores in Osaka, Nagoya, and Kyoto, and in 1743, he opened the Edo store in Nihonbashidori Tori-hatago-cho. By the time Hiroshige painted this picture, Echigoya, Shirokiya, and Daimaruya were the three major Silk-goods Lane in Edo.

In the Meiji era, however, the aspect of the street changed a little with the development of the road. The Oshu Kaido, which used to be right in front of Daimaruya, moved to the north and became no longer the main street.

Later, with the development of the railroads, the flow of people changed, and in 1910, Daimaruya closed its Tokyo branch, which had operated in Ohtenmacho for 167 years, and moved its base to the Kansai region. The photo in the book published in 1919 is already a building for a shipping company.

And this is the current "where Daimaru-ya used to be". There are still many textile companies in the area from Ohtenmacho to Yokoyama-cho, but there was also a textile wholesaler building on the former site of Daimaru-ya. Of course, this is not the main street, but now a back alley.

I have tried to fit the current picture into the actual Hiroshige painting.

At the time, the Kanda and Sanno festivals were the two largest festivals in Edo, which were held in rotation every year because they were too expensive. The largest float was the first one to go out every year in Ohtenma-cho. You can clearly see that the Silk-goods Lane in Ohtenma-cho were the driving force of the Edo economy at that time.

Looking at the current picture, one can imagine a prosperous decline. However, Daimaru, which once withdrew from Tokyo, is now the main tenant in the Osaka Station Building and the Yaesu Exit of Tokyo Station, which has been redeveloped.

The town depicted by Hiroshige is clearly moving.

I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando, one of my favorite artists, to see how the scenes look today.

I visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando, one of my favorite artists, to see how the scenes look today.

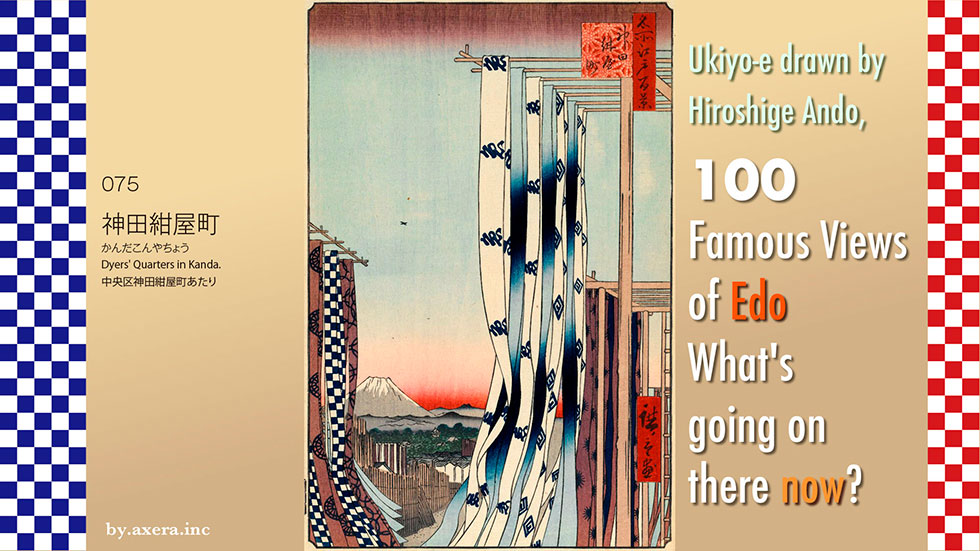

The "Dyers' Quarters in Kanda" of 075 depicts Mt. Fuji seen through the fabric hanging from a clothesline in Konyacho, a dyeing town at that time.

First, please note the location of this town.

The town of dye artisans was located about 2.5 km east-northeast of the Edo Castle keep at that time, about 200 m east of the current JR Kanda Station.

Please see a slightly larger map. The intersection of Showa Dori and Kanda Kanamono Dori still retains the intersection name of Konyacho. Hiroshige probably painted the view looking toward the south exit of Kanda Station from this area. I have used a red gradation to represent this viewpoint.

This map is covered by an old map. This is the Aizome River, where dyed fabrics were exposed to water to remove the dye before being made into products.

Konyacho was a town of dyeing artisans ruled by Tsuchiya Goroemon, who was allowed by the shogunate to purchase indigo from the Kanto and Izu regions as a head dyer. The term "konya" originally referred to craftsmen specializing in indigo dyeing, but by this time the term had come to refer to "dyers" as a whole.

The name "Edo purple," derived from the fact that it was dyed in Edo using Murasakiso, a plant native to Musashino, became popular, and the hachimaki, dyed with indigo, became even more popular when Sukeroku, a popular Kabuki playwright, wrapped it around his head and performed it. The term "out of place" was even coined for items dyed outside of Kanda Konyacho, which had become popular for its chic and fashionable dyed goods.

Konyacho is famous for the classic rakugo story "Koya Takao," based on a true story.

Kyuzo, a servant of Kichibei, a dyer in Kanda Konyacho, is a serious man. He saves up money by not eating or drinking for three years and goes to Yoshiwara under the pretense that he is the son of a famous shopkeeper in Kasukabe.

When Takao first asks him socially when they can meet again, Kyuzo cries and reveals his true identity honestly, showing his indigo stained hands. Hearing this, Takao also bursts into tears and says that he is glad that he has thought of him for three years, and that his contract will be terminated on March 15 of next year, so he asks her to be his wife then.

There were actually eleven "Takao Tayu," the traditional name of the Miuraya family for generations, but the originator of this story was the fifth generation of the family, who was called Dazome Takao. Kanda Otama married into Kurobei Konya of Otamagaike and manufactured hand towels using a mass-production dyeing method called dazome, which became very popular among the playboys of the time. All of the Takao Tayu except for the fifth generation lived miserable lives, but only the fifth generation Takao is said to have given birth to three children and lived to be over 80 years old.

Let's actually take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

The first thing that catches the eye is the indigo-dyed fabric hanging from the clothesline, which is set up on a high tower, and swaying in the wind. The indigo-dyed yukata fabric is dyed in indigo, as is typical of a konya town, and has a design of the character "fish" for Uoei, the publisher, and Hiroshige's katakana character "hiro.

Fuji at sunset in summer in the distance, with the mountains of Tanzawa and Chichibu surrounding it in the foreground and background. In the foreground are the turrets and storehouses of Edo Castle surrounded by greenery and the streets of Edo.

On the left side, fabric dyed with the then-popular Daihachi wheel pattern and a traditional indigo checkered pattern flutters in the wind.

The area below was confiscated by the shogunate as a fire prevention area because of frequent fires. However, as time progressed, buildings were permitted as long as they were made of reed screens that could be removed immediately in the event of a fire.

In fact, Katsushika Hokusai had painted the same subject matter several years earlier in his Fugaku Hyakkei (One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji). It is said that Kanda Konyacho may be a perfect example of Hiroshige's extraordinary rivalry with Hokusai's Fugaku series.

I actually went to this location.

Directly behind the shooting location is the intersection of Showa-dori Konyacho cross. The road in front of us is Kanda Kanamono Dori, and the signal ahead is Imagawabashi Bridge. The guard ahead is the south exit of Kanda Station. Passing through the guard and turning left, you will come to Ryukanbashi Bridge, which ends at the outer moat of Edo Castle.

The skyscrapers far ahead are the Otemachi Place, the Otemachi Building of NTT, and the Otemachi Financial City, where the Museum of Posts and Telecommunications has been reconstructed.

I tried to fit the current view into Hiroshige's painting. Although it does not quite fit in terms of height and size, I tried to composite Mt. Fuji in summer after the buildings of Otemachi.

Today, not a single dyeing shop remains in the Kanda and Konyacho neighborhoods. Due to urbanization and the reclamation of the Aizome River, the craftsmen of Konyacho moved to the banks of the Kanda and Myoshoji Rivers. However, nowadays, with the promotion of chemical dyes and the diversification of dyeing methods, there is no longer even a need for a river to wash out the dyes as long as there is a water supply.

Originally, indigo-dyed fabrics and clothing were used for their insect repelling and deodorizing effects, and their slightly used colors were also valued. The scene of drying yukata fabrics fluttering with kouya-takao seems to be disappearing more and more.

I visited my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scenes look like today.

I visited my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scenes look like today.

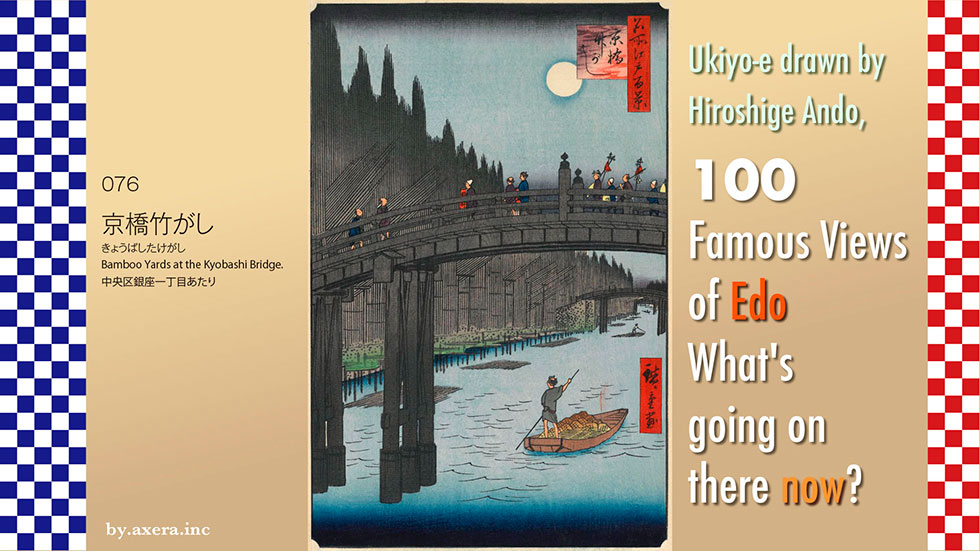

Bamboo Yards at the Kyobashi Bridge" (076) depicts the view of Kyobashi from the Edo Castle side.

First, please check the location of this bridge on Applemap. It is about 1.5 km southeast of the Edo Castle keep, south of Kyobashi station on the current Ginza subway line.

On a slightly more enlarged map, the location of the Kyobashi bridge is shown in purple, and a red gradient is added where Hiroshige's viewpoint would have been.

Let's put this over a pictorial map of the time. You can see that the Kyobashi River has shifted slightly just around the bridge. Now, the Kyobashi River is covered by the Tokyo Expressway.

Let us take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

Looking at the painting as a whole, it appears that it was painted at dusk in summer, just as the moon was beginning to rise, looking from the Edo Castle side over the Kyobashi Bridge to the banks of the Kyobashi River, which serves as a bamboo yards.

At the top of the painting, the moon, which has just emerged, is floating in a puddle, and on the left side, a bamboo is propped up like a wall. If you look at the painting calmly, you will immediately notice that the length of the bamboo, as well as the height of the bridge, is quite exaggerated up and down, which is interesting.

In the middle of the bridge, you can see a Giboshi painted on the bridge. Of all the bridges in Edo, only Nihonbashi, Shinbashi, and this Kyobashi bridge were decorated with these Giboshi, and these bridges were managed by the Edo shogunate. It is said that this Giboshi comes from "houju," the urn of the Buddha. On the other hand, it is also believed to be a corruption of the word onion-head, and the unique smell of leeks was believed to ward off evil spirits.

Although the bridge is no longer there, the main pillar of the Kyobashi bridge, decorated with giboshis, still remains at the site.

On the right side of the bridge is a depiction of a group of pilgrims who have just returned from a visit to Oyama. At that time, although Ise pilgrimages were also popular, the Oyama Pilgrimage was more convenient and could be completed in a few days, so it was popular for people in the town to organize a group to go to the Oyama mountain.

The way to Oyama was via Mizonokuchi and Tsuruma, passing through what is now National Route 246 and the old Oyama Oukan. On the way back, they often visited Benten-God in Enoshima from Isehara and returned on the Tokaido Highway through Kanagawa and other areas. Hiroshige's painting depicts some group of lecturers arriving at Kyobashi just at dusk.

Please also see Hiroshige's painting of the group on a pilgrimage to Oyama and Enoshima.

The northeast side across the Kyobashi Bridge was called Takegashi (bamboo yards). This area was called Takeya-machi or Bamboo Town, where many bamboo wholesalers and bamboo craftsmen lived side by side. At that time, bamboo was very useful as a familiar, lightweight, and highly workable material that could be processed into a variety of tools as well as ceiling, wall, and hedge materials.

Bamboo was transported in rafts, mainly from Chiba and Gunma. In front of the bamboo riverbank, unraveled bamboo rafts are still floating.

If you look more closely, you can see bamboo products piled on the cargo of the boat, which is operated by a boatman.

Across Kyobashi Bridge from Takegashi, the other side of the bridge formed a vegetable market for produce called Daikongashi. Daikongashi was officially approved as Kyobashi Daikongashi Market during the Meiji period (1868-1912), and flourished as a produce market until the early Showa period (1926-1989) when Tsukiji Market was opened. Please take a look at Kawase Hasui's painting there. In the painting on the right, Kyobashi is depicted quite small beyond the river. This shows how Hiroshige exaggerated the size of the bridge, which makes us laugh a little.

Well, now I went to see what this place looks like.

It is a bit surprising, but here is a picture of it.

In 1959, Kyobashi River was reclaimed and Kyobashi Bridge was removed. A new Tokyo Expressway was built above the Kyobashi River, and below it are the stores shown in the photo, with the basement used as a parking lot. This photo shows the current view from the point where Hiroshige painted, but there is no trace of the past.

At the foot of the bridge, viewed from the Ginza side, stands a restored gas lamp that was installed between the bridge and Kanasugi Bridge in 1874.

This is Ginza as seen through Kyobashi Bridge, which is no longer there. From here on, the area becomes a pedestrian paradise on weekends.

On the opposite side of Chuo-dori, one can see all the way to Nihonbashi, and the most recent intersection is named Kyobashi, where the Kyobashi station of the Ginza subway line is located underground.

I actually tried to fit the current Kyobashi into Hiroshige's painting. The sky is not even visible, and the result is somewhat staggering, but this is what it looks like today.

The cold steel frame of the expressway, covered from the sky, gives a frightening sense of oppression, and beneath it, cars made of steel, not water, are stagnant. Neither the rising moon painted by Hiroshige nor the rising sun by Hasui can be seen from here anymore.

I visited my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like today.

I visited my favorite 100 Famous Views of Edo, painted by Hiroshige Ando, to see what the scenes look like today.

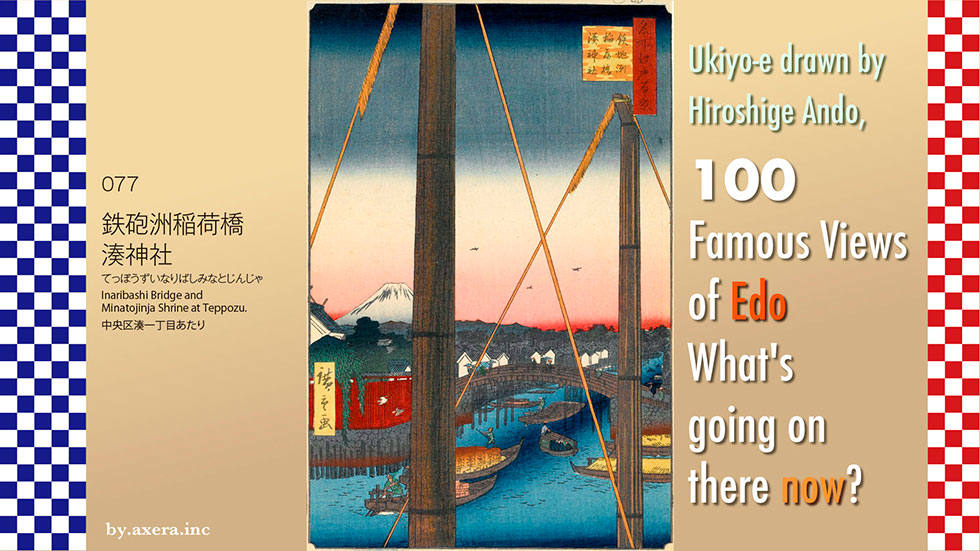

"Inaribashi Bridge and Minatojinja Shrine at Teppozu" in 077 depicts the Hacchobori, which used to flow into the Echizenbori, from the river mouth side.

First of all, please check the location where this painting was painted on a modern map.

Just about 500 meters southeast of Hatchobori Station, there is a place where the river has a slightly unnatural shape. I have circled it in red.

Please see a slightly larger map. Although there are no moats or rivers to be seen here now, in fact, during the Edo period, the Hatchobori River flowed from east to west where Sakuragawa Park is located. You can also see on the map that the buildings are somehow unnaturally missing.

Therefore, I have drawn the blue river and the yellow Inari-bashi bridge on the map. This river changed its name from the mouth to Hatchobori, Sakuragawa, Kaedegawa, and Kyobashigawa as it approached Edo Castle, and connected to the Uchibori moat surrounding Edo Castle. It is about the east side of the Tokyo Forum today. However, in 1959, the river was reclaimed and transformed into an expressway, park, drainage facility, and sewerage system.

On this map, Hiroshige's viewpoint is shown in red gradient, and an old map of the time is overlaid. The location depicted by the red triangle near the mouth of the river is Minato Shrine. On the north side of the Inari Bridge is Takabashi, and flowing below it is the current Kamejima River, the Echizen moat dug to enclose the lower residence of Matsudaira Echizen no Kami.

The south side of Echizen moat was already open sea at that time with only Tsukudajima Island to the east. From here to Shibaura area was called Edo Minato, an important port facility of the Edo shogunate.

When Tokugawa Ieyasu came to Edo, the inlet of Hibiya entered the area close to Edo Castle, and at that time, this area was a large, bow-shaped Sumida River sandbar in the shape of a gun. This sandy area, called Teppozu(sandbar of gun), was later developed and reclaimed to the extent that it became connected to Edo Castle, forming towns such as Honminato-cho and Akashi-cho.

Here is a little bird's-eye view of this area from Edo Meisho Zue (Edo Famous Places), so please take a look at it in detail. The Hatchobori flows from the lower left, and when it crosses the Inari Bridge, it joins the Echizenbori coming from the left side to form the Edo Minato, where large ships berth. The Sumida River flows in from the upper left, crosses the Eitai Bridge to the right, and meets Tsukudajima Island, dividing it into two halves.

In order to make the location of the two rivers easier to understand, I have used a red gradation to represent Hiroshige's point of view in this painting as well. How do you like it?

What is noteworthy here is the large number of ships that docked at the Edo port. These large vessels, called higaki-kaisen and taru-kaisen, came from the Kansai region and brought rice, indigo beads, sake, soy sauce, and other commodities. Cargoes arriving at the Edo port were transshipped onto smaller boats called setoribune and chabune, which carried them to the various river banks using the moat walls that crisscrossed the city.

Since large ships came mainly from the Kamigata region, their goods were called "kudari-mono" by Edo citizens, a synonym for high quality goods. Conversely, sake and other alcoholic beverages made in Edo were not very tasty, and were distinguished by calling them "kudaranai-mono (crap).

Hiroshige also made good use of the sailposts of these large ships in his other paintings of this neighborhood.

The people involved in these vessels that actively came and went placed great trust in the Minato Shrine, also known as "Nami-yoke (dodge waves) Inari. It is said that this old shrine was built in the Heian period (794-1185) and was located at the confluence of the Kyobashi and Kamejima Rivers around the beginning of the Edo period (1603-1868).

In 1790, a Fuji mound made of lava from Mt. Fuji was built on the grounds of Minato Shrine, and the mound, larger than the main shrine, became a popular spot for Edo citizens. However, in 1868, a few years after Hiroshige painted this picture, the land of Minato Shrine was expropriated and the shrine was moved about 120 meters to the south.

In addition, Hiroshige also painted a picture of the Minato Inari Shrine's Fuji Pilgrimage. You can see that the Fuji mound was on the sea side. In addition, many large ships are anchored offshore.

Let's take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

Two pillars are standing under the blue gradation of the sky, and they are secured by two ropes. These are the sail masts of a large ship anchored in Edo Minato. The fluffy material hanging from the top of the ropes is called hozuri, which is made of hemp and is used as a cushioning material to prevent damage to the sails from rubbing against the ropes when the sails expand with the wind.

The distant view in the center depicts Edo Castle, Mt. Fuji, and many roofs of buildings in the direction of Ginza. On the left side of the painting, surrounded by a red wall, is the Minato Shrine, and the bridge over it is the Inari Bridge.

The moat running under the bridge is Hatchobori, which was connected to the inner moat of Edo Castle under a different name.

A small boat, which has reloaded its cargo from a larger vessel, is now heading up the moat. If you look closely at the cargo, you can read the word "tea" on it. The boat in the foreground, operated by the boatman, appears to be loaded with sake barrels. Hiroshige must have actually checked this situation with his own eyes. After all, Hiroshige's residence at that time was about a 15-minute walk from here.

I actually went to the place that serves as Hiroshige's viewpoint. The Minato Shrine was located around the three buildings on the left. The black and white building behind the street trees in front was the Sakurabashi Pump Station, where the Inari Bridge crossed and the Hacchobori River flowed below.

In front of the pump station, only the nameplate that says there was a bridge still remains forlornly.

I went to the rooftop of the pump station, which is open as a park. It is an artificial grass park surrounded by buildings like this, and there is not the slightest sign that it used to be a river.

This is the relocated Minato Shrine, now called Teppozu Inari Shrine.

When we went around to the back, we found a cozy but still standing Fuji Mound made of lava from Mt.fuji.

I tried to fit the current view into Hiroshige's painting.

Fuji in Google's Street View to make it look more like a summer landscape.

The peaceful and tranquil view of Edo is not there, and the picture is rather unemotional, with Mt.Fuji. On the lower side of the view surrounded by two sail pillars, there was indeed water flowing in the past, and ships came and went, which was Edo's vital logistics network.

Today, highways and trucks have replaced rivers and boats, and rivers have been replaced by sewers. It makes me think a bit about whether such modern reclamation and development is a "Kudari-mono" (good thing) or a "Kudaranai-mono" (crappy, bad thing).

I visited my favorite "Meisho Edo hyakkei" (One hundred Famous Views of Edo) painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what those scenes look like today.

I visited my favorite "Meisho Edo hyakkei" (One hundred Famous Views of Edo) painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what those scenes look like today.

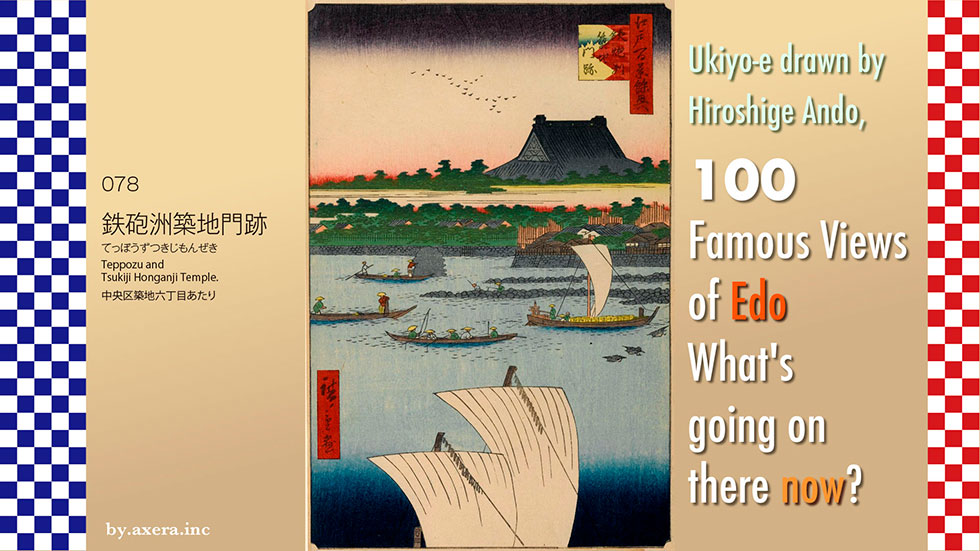

"Teppozu and Tsukiji Honganji Temple" in 078 is a view of the current Tsukiji Honganji Temple as seen from the sea at that time.

First, please check AppleMap to see where this view was painted from.

This is the view from the southeast side of Tsukiji Honganji Temple, around the current Sumida River. The red gradation represents Hiroshige's viewpoint. Now it looks as if we are looking from around Tsukishima 5-chome on the other side of the river, but in reality, this was still the sea at that time. Let's put a map from the Tempo era over it.

This map shows that the Honganji site, painted in red, had the main building on the northeast side and a number of subsidiary buildings on the southwest side. Today, Harumi Street runs through the middle of the site, and the area where the subsidiary buildings were located is now an attached store of the Tsukiji Fish Market. The Tsukiji River on the southeast side is now a parking lot and park.

Here is a brief history of Honganji temple.

Tsukiji Honganji Temple is a direct affiliate of Nishi Honganji Temple in Kyoto, which was originally located in Asakusa Hamacho and was moved and reconstructed. The original Nishi Honganji, Asakusa Mido, was founded in March 1621. The location is around today's Higashi-Nihonbashi Station on the Toei Asakusa Line.

However, on January 18, Meireki 3 (March 2, 1657), a major fire broke out that burned most of Edo. The Meireki Fire was the most devastating in the Edo period, destroying almost all of Edo, except for a portion of the inner Sotobori moat, as well as the Edo Castle, including the castle keep, numerous daimyo residences, and most of the city center. The death toll is recorded at 30,000 to 100,000. Nishi Honganji Temple was also destroyed by fire.

The fire forced the Edo Shogunate to rethink the city's disaster prevention system and urban planning. Because of this, Nishi Honganji was not allowed to rebuild in its original location, and the sea off Hacchobori was chosen as an alternative site. The Tsukudajima monks took the lead in reclaiming the sea and building land to rebuild the main temple building, which was reconstructed in 1679 at the current location and came to be known as "Tsukiji-monzeki" (Tsukiji Honganji Temple). This "Tsukiji" means reclaimed land.

Now, let's put another map on top of the original map that shows the division of wards. The red area is Honganji Temple, and the white area is mostly occupied by daimyo residences. The gray areas are the townhouses where Edo citizens live. This map was drawn about 50 years before Hiroshige painted this picture. Since the relocation of Honganji Temple, the Tsukiji area has been reclaimed and Edo's functions as a bay city have been improved.

Furthermore, let us put a map of the area in the early Meiji period, more than ten years after Hiroshige painted this picture.

By this time, the number of military facilities in the area around Tsukiji Honganji Temple, shown in red, had increased.

After the arrival of the black ships in 1853, the Edo Shogunate rushed to build the Shogunate's navy and focused on strengthening maritime defense capabilities in various parts of Japan, especially in the Edo area. After the Meiji Restoration, this changed to military-related facilities.

In 1869 (Meiji 2), the Tsukiji Settlement for foreigners was established in Akashi-cho, which became the center of the civilization and the Unjyo-sho (now Tokyo Customs). The location of the settlement was right around the water's edge in Hiroshige's painting.

Here is a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

First, the large roof of the Tsukiji Honganji temple is depicted, looming large above the sky, with a haze of clouds below it. This is an ingenious move by Hiroshige to avoid being blamed by the Shogunate by depicting the military facilities in the area at the time. At the time, the roof of the main hall of Tsukiji Honganji Temple was so large and symbolic that it could be seen from all over Edo.

On the right is Akashi-cho, and on the left is the quay of Minami-Iida-cho. In the foreground are fishermen casting cast nets, and fishermen about to cast their nets are depicted. The area is famous for kiss fishing, and a fishing boat is also depicted.

Next to the Eurasian-oystercatcher, a small boat, apparently carrying sake barrels, is moving up the river. At the bottom, a large boat from the Kansai region is sailing north.

Here is a bird's eye view of Tsukiji Honganji Temple from Edo Meisho Zue. In the bird's-eye view from the south, the road from the upper left to the lower right toward the sea is now Harumi-dori Avenue.

Hiroshige also painted a series of three series, depicting the Tsukiji Honganji Temple as a bird's-eye view from the area around the present-day National Cancer Center. As expected, he used a lot of hazy clouds to blur the military facilities. The gate on the lower left is the intersection of what is now Tsukiji 4-chome cross, and the road from there toward the sea on the upper right is what is now Harumi-dori Avenue.

This photo was taken from the top of Mt. Atago seven years after Hiroshige painted this picture. The large roof of Tsukiji Honganji Temple is clearly visible.

This photo was taken from the Uneme Bridge (around today's Shinbashi Enbujojo) to show the repair of the large roof that was damaged by fire in 1872.

This is a photo of the main building, which has been rebuilt, taken from the front. At that time, the front of the building was facing in the direction of today's Harumi-dori Avenue.

This is a photo of the front of Honganji Temple in 1893, when the gas lamps were installed in front of the gate.

This is a photo of the large roof of Tsukiji Honganji Temple published in "One Hundred Contrastive Views of Edo, Now and Then" in 1919. It appears to be an actual view from Hiroshige's point of view at the time. The white building on the right is believed to be Tokyo Customs.

I actually went to this location.

This is the photo. The big roof of Tsukiji Honganji Temple should be visible on the right side of the brown building, but it is not visible at all.

This is the north side of the Tsukiji River, which is now a park.

It is now a parking lot, south of the Tsukiji River.

This is the roof of Tsukiji Hongwanji Temple, which can be seen from the entrance of its parking lot.

This is the current front of Tsukiji Honganji Temple.

The temple was again destroyed by fire after the Great Kanto Earthquake of September 1, 1923. On the south side, the 58 subsidiary buildings of the Honganji temple were relocated due to rezoning, and later became a group of stores next to the Tsukiji fish market.

The present main hall was designed by Chuta Ito in 1934 in the ancient Indian style, with the front facing the Ginza side. It is a fashionable complex with a reinforced concrete structure, which was unusual for a religious facility at that time, and is richly decorated with marble carvings.

There is also a fashionable cafe next to the main hall.

I actually tried to fit the current photo into Hiroshige's painting.

Of course, the main roof of Honganji is not visible at all.

Hiroshige published this painting in July of Ansei 5, the last in the series. At first, this 78th and the next 79th views were not included in the Meisho Edo Hyakkei (One Hundred Famous Views of Edo), but were treated as appendices and named "Edo Hyakkei Yokyo (One Hundred Famous Views of Edo)," but later they were officially included in the Meisho Edo Hyakkei.

On the other hand, after the Kansei Reforms (1787-1793), the shogunate controlled the thought of not only the samurai but also the populace through publication controls and other measures. This was a time of considerable tension in the world, especially with the arrival of the black ships.

If anyone depicted military facilities in the Tsukiji Honganji area in an ukiyoe, the entire "Meisho Edo Hyakkei" (One Hundred Famous Views of Edo), including the publisher, could be subjected to considerable punishment. Concerned about this situation, Hiroshige may have used a lot of haze clouds to hide anything that might reveal the secrets of the regime.

Furthermore, although the Tsukiji Honganji Temple was spared from collapse in the great earthquake of Ansei 2, the following summer a typhoon caused a tidal wave that not only destroyed the large temple, but also washed away the surrounding townhouses. Therefore, the view that Hiroshige saw was completely different from the one depicted in the painting.

The temple, which has survived various disasters, has now changed its official name from "Honganji Tsukiji Betsuin" to "Tsukiji Honganji". A project is underway to make the temple more open to foreigners and other visitors regardless of denomination, and various lectures and events are being held. Although the main hall is not visible from many places in Tokyo, it has become a representative face of Tsukiji, both in appearance and content, and Shinran Shonin might have been surprised to see it. I replaced the entire image with a photo of the front of Hongwanji Temple.

I visited my favorite "Meisho Edo hyakkei" (One hundred Famous Views of Edo) painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scene looks like now.

I visited my favorite "Meisho Edo hyakkei" (One hundred Famous Views of Edo) painted by Hiroshige Ando to see what the scene looks like now.

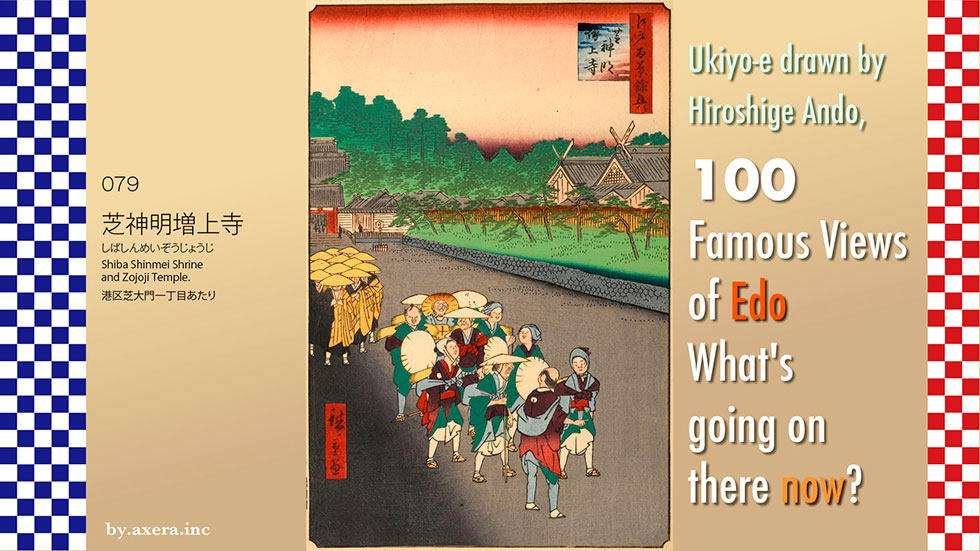

The "Shiba Shinmei Zojoji Temple" (No. 079) is a view looking toward the Zojoji Temple Daimon Gate from near the current Daiichi Keihin Daimon intersection. This painting was released to the world at the end of the Edo Hyakkei series, as a supplement to the Edo Hyakkei series.

First, let's check this location on AppleMap.

The big green color on the left of the map is Zojoji Temple. The road running north-south at the Daimon intersection in the middle is Tokai-do Road, and JR Hamamatsucho Station is on its right.

The red gradient represents Hiroshige's viewpoint.

I put a map of the time on top of it. You can see how big Zojoji Temple was at that time. The red area surrounding the temple was used as a dormitory. The road with town names in vertical lines is Tokai-do Road, which was already the sea from Hamamatsucho Station to the present Hamamatsucho Station. You can see that Kii-dono's mansion was changed to the present Shiba-Rikyu.

At the time, Hiroshige painted this overhead view of Zojoji Temple and Shiba Shinmei. As you can see, the roads and main facilities are similar to the current layout.

I added explanations of the buildings. How do you like it? The location of the buildings is now much easier to understand. I also added a red gradation, which is Hiroshige's point of view.

Walking from the Tokaido side on the lower right, you will see Shiba Shinmei Shrine on your right, cross a bridge, and pass through a Daimon gate. In front of the Daimon gate, the Sakuragawa River flowed from a reservoir on the right and emptied into the Furukawa River on the left.

Beyond the Daimon gate, a row of pine trees in Shiba Park, which still remain today, appear on either side, and in front of you is the temple gate.

Passing through the gate, the main hall appears. The basic layout of this area is exactly the same as today.

Finally, I put Applemap street view over it. Roughly speaking, you can see that the location of the buildings has kept the relationship depicted by Hiroshige.

Let us now take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

This painting is striking in that the title "Edo Hyakkei Yokyo" (Appendix of One Hundred Famous Views of Edo) follows the 78 views.

The red gate on the left is the Daimon gate at the entrance to Zojoji Temple, followed by the Sanmon gate, and the roof of the main hall is also depicted behind it.

The building on the right with the distinctive roof topped with Chigi is the Iikura Shinmei-gu Shrine, commonly known as Shiba Shinmei Shrine. The festival lasts from September 11 to 21, and was also called the "Ginger Festival" because of the ginger market, which was believed to have various medicinal properties at the time. Chigi is a roof decoration that seems to be a feature of the shrine's architecture, but during the festival, a three-tiered wooden good-luck gift called "Chigi-bako" was sold as a souvenir.

The area around Shiba Shinmei Shrine was lined with kabuki stalls, freak shows, yokyu-jo (archery stalls), and koshaku and rakugo (comic storytelling) stalls, forming the most lively area on the south side of Edo. It was in the precincts of Shinmei Shrine that the famous fight between firefighters and sumo wrestlers in the kabuki play "Megumi no kenka" (Fight of the Megumi) took place, and even resulted in a court case.

In front of the Daimon gate, the Sakura River runs through it, and a dozen monks are now walking toward us across the bridge. This group of monks was known as the "seven monks(Nakatsu-bozu)" because at seven o'clock (around 4:00 p.m.) near nightfall, they went begging for alms all over Edo City.

These seven monks not only served as mendicants, but also as Edo's security force, and there is a document that introduces them as "punishing those who misbehave in the town.

The group in the lower center, with kimono hem rolled up, tights on their feet, and holding hats, looks like a group of people from the provinces on a tour of Edo. After visiting Zojoji Temple, they seem to have returned to Tokaido and headed for the center of Edo.

I actually went to this place. It seems that Hiroshige painted roughly the left half of this picture. Unusually for this series, the town remains as it was divided at that time, and the Salmon gate can be seen after Daimon gate, but unfortunately, the Shinmei Shrine is not visible.

I swung the camera from the entrance to the Shiba Shinmei shopping street in the direction of the Zojoji temple Daimon gate.

This is the present-day Shiba Shinmei Shrine. Originally a dining hall of the Ise Jingu Shrine, it was called "Iigura Mikuri," and was originally located near the current Tokyo Tower, but was moved to its current location when Zojoji Temple relocated it, and was then called "Iikura Shinmei-gu Shrine.

Later, when a town was established in the Shiba area, the shrine was called "Shiba Shinmei Shrine," and from the early Meiji period, it became "Shiba Daijingu," a name associated with the Emperor's family.

This is the Daimon Gate, which was reconstructed in concrete by the City of Tokyo in 1937 with donations from citizens. The road running on both sides used to be Sakuragawa River, and a bridge was built at the intersection.

This is the Sanmon gate of Zojoji Temple that survived the war, and it is called the San-Gedatsu-mon Gate, which was built in 1621 and is now designated as a National Important Cultural Property. It is said that by passing through this red gate, one can be liberated from the three worldly desires, namely greed, hatred, and delusion. Now, please try it for yourself to see if you can actually be liberated from them.

This is the present main hall. It is said that the predecessor of this temple was Koumyouji Temple of the Jodo sect, which was built in the 9th century by a disciple of Kukai in what is now Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo.

Later, it became a family temple of the Tokugawa family, and with the expansion of Edo Castle, it was moved to its current location in Shiba by Ieyasu in 1598. According to feng shui theory, Kaneiji Temple was placed in Ueno, the demon's gate of Edo Castle, and Zojoji Temple was moved to the suppression of Shiba, the demon's back gate of Edo Castle.

The Tokyo Tower can be seen behind the main hall, and the high-rise building behind it is the construction site where Azabudai Hills is currently being built as part of the redevelopment of the Azabudai area.

Now, I inserted the current view into Hiroshige's painting.

Shiba Shinmei Shrine is not visible behind the building, but it is still in the same condition as it was at the time of the road location. The Shiba Shinmei Shrine with its roof covered with a Chigi is originally visible after the Risona Bank, but you cannot see it.

At the end of the Edo period, after the appearance of the black ships in Edo Bay, the balance of power between the Kyoto Imperial Court, the Edo shogunate, and its domain system was shifting, and even citizens somehow believed that the Tokugawa era would end. A few years after Hiroshige painted this picture, a coalition of Satsuma and Choshu, with the Emperor in their saddle, successfully staged a coup d'etat called the "Meiji Restoration. In Hiroshige's painting, the main gate of the Tokugawa family's family temple, the Daimon, is trimmed in half, and the Shiba Shinmei Shrine, known as the "Ise-san of Kanto" and associated with the Emperor family, is depicted significantly overhanging its original position.

The same number of ordinary people are depicted in the foreground, larger than the seven priests of Zojoji Temple. It is in this area that I sense the painter Hiroshige's comprehensive sense of the times.

I actually visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando, one of my favorite artists, to see what the scene looks like today.

I actually visited the 100 Famous Views of Edo painted by Hiroshige Ando, one of my favorite artists, to see what the scene looks like today.

The "Kanasugibashi Bridge and Shibaura Inlet" in 080 is a view from near today's Daiichi Keihin Kanasugibashi Bridge, looking almost northeast-east toward the sea. At the time of Hiroshige, the ocean was immediately visible from this bridge.

First, please check Applemap to see where this picture was drawn from.

Kanasugibashi Bridge is located southwest of JR Hamamatsucho Station, where today's Daiichi Keihin and the old Tokaido cross over the Furukawa River.

The red gradient is Hiroshige's point of view, and a map of the time is also shown. The large red area is Zojoji Temple, and the white area is the samurai residences. The gray area here is the machiya area, where the townspeople lived. South of Kanasugi Bashi Bridge is Kanasugi, around today's Shiba 1-chome, and south of Kanasugi Bashi Bridge, across a small creek, is Honshiba, around today's Shiba 4-chome. When Tokugawa Ieyasu came to Edo in 1590, these two villages were small villages facing the sea where about 10 fishermen lived.

Later, these fishermen saved Ieyasu's pleasure boat from running aground in the Edo harbor, and as a reward, Ieyasu gave them permission to catch fish anywhere in Japan. In addition, the sea around here has long been a rich fishing ground for shellfish, eels, shiba shrimp, flounder, and black sea bream, and the fish market here developed and was nicknamed "Zakoba" by the common people of Edo.

The map is slightly raised to show the area to the south.

That is where the famous rakugo story "Shibahama" was born.

Katsu, a fishmonger, is a skilled but alcoholic, and lives a life of poverty, making mistakes all the time. His wife wakes him up early that morning, and he goes to the beach at Shibahama and picks up a leather wallet containing a large sum of money.

The next day, his wife tells him that he did not pick up the wallet and that he must have been dreaming.

Three years later, he has a store on the main street and his life is stable. On New Year's Eve, while listening to the bells of Zojoji Temple, his wife tells him that she really did pick up the wallet three years ago.

The synopsis goes like this, but this Katsu lived around Kanasugi, and the place where he picks up the wallet is the beach of Honshiba, around what is now Shiba 4-chome. The area around today's JR line is already the sea, and this area was a beautiful sandy beach called Sahama in the Edo period, where fishermen used to dry their nets.

Now, let us actually take a closer look at Hiroshige's painting.

Various things are being displayed in the sky, but on the bridge, a group of lecturers are passing each other on their way to the Oeshiki ceremony and another group of lecturers are returning home after visiting the ceremony. Oeshiki is a festival held on October 13, the anniversary of Nichiren's death.

The group in the foreground is a group of lecturers about to head for the Oeshiki, and they are heading in the right direction with the brown Tenugui on the left, called "tamaneki," and the blue Tenugui on the right. A red banner with the theme written on it is also fluttering under the umbrella and hanging down with a crest of tachibana on the well representing Nichiren sect. On the right side of the umbrella, the words "Minobu-san," the head temple of Nichiren sect can also be seen.

The group in yellow hats on the ocean side is a group returning to Edo City to the left after the Koh. They are crossing the bridge while chanting the Buddhist chant and rhythmically beating the "Hokke-no-Taiko" (drum of the Uchiwa). This area is very Nichiren-shu, and you can almost hear the sound.

If you cross the Kanasugibahsi Bridge and continue further south on the Tokaido, over Yatsuyama and along what is now Ikegami-dori, you will reach Ikegami Honmonji Temple, the place where the founder Nichiren died. Hiroshige also depicted the Oeshiki ceremony at this temple. This ceremony is still held today, and tourists from all over the country flock to the Manto-Kuyou (memorial service for many lanterns) held on the eve of the festival.

In addition, please take a look at the painting on the right, the Kanasugi Bridge, which I found painted by Hounen Tsukioka in the exact same composition as Hiroshige. It's just a group of lecturers in a daimyo's procession.

I actually went to this location.

The picture is confusing because of the Metropolitan Expressway passing above.

This is a view from a little closer to the north. In front of you is National Route 15, Daiichi Keihin. The Metropolitan Expressway Loop Line passes above to the right, and the Hamasakibashi Junction is just ahead. The building with the red radio tower in front is the Tokyo Gas head office building.

This is an animation looking toward Daimon and Shimbashi from Kanasugi Bridge.

This is a view from Kanasugi-bashi Bridge toward Shiba 2-chome. At the far end of the building is the Satsuma Domain warehouse where Kaishuu Katsu and Takamori Saigo met at the end of the Edo period and decided to open the Edo Castle without bloodshed.

Looking upstream of the Furukawa River from Kanasugibashi Bridge, you can see this.

The upstream bridge you can see is the Shogun Bridge, and if you continue upstream, from the Azabu Juban, Hiroo, and Shibuya Station area, the river is renamed the Shibuya River and is mostly a culvert, reaching the Shinjuku Gyoen area via Harajuku Cat Street.

I tried to fit the current photo into Hiroshige's painting.

It is a very boring picture, as you cannot see far into the distance.

Even at that time, Kanasugi-Bashi Bridge here was not a famous place of interest, but merely one of the bridges on the Tokaido. It was also omitted from "Edo Meisho Zue", a compilation of famous places in Edo that was compiled in considerable detail.

This painting was published in July of 1853, so there are still many days until the Nichirens Oeshiki Ceremony in October. A possible explanation is that the painting was commissioned by Ikegami Honmonji Temple. The artist may have been calling for people to come and see the rhythmic Uchiwa drumming and the Manto Kuyo (Buddhist lantern offering) on the eve of the ceremony.

Furthermore, since the time of the festival was marked by political unrest, the red banner in the center of the painting may have been a wish for everyone to chant "Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo" and go to paradise in peace.

Perhaps his wish was answered, for 10 years after Hiroshige painted this picture, the castle of Edo was conquered without bloodshed.